Water is transparent, tasteless, odourless and virtually colourless. It is vital for all known forms of life and covers over 70% of the Earth’s surface. We use it in cooking and washing and, along with ice and snow, it is central to many sports and other forms of entertainment such as swimming, fishing, diving and skiing. Unsurprisingly, its also been a source of inspiration to composers for hundreds of years so let’s take a look at some of the music that has been inspired by water…

Felix Mendelssohn

Hebrides Overture

Concertgebouw Orchestra

Bernard Haitink (conductor)

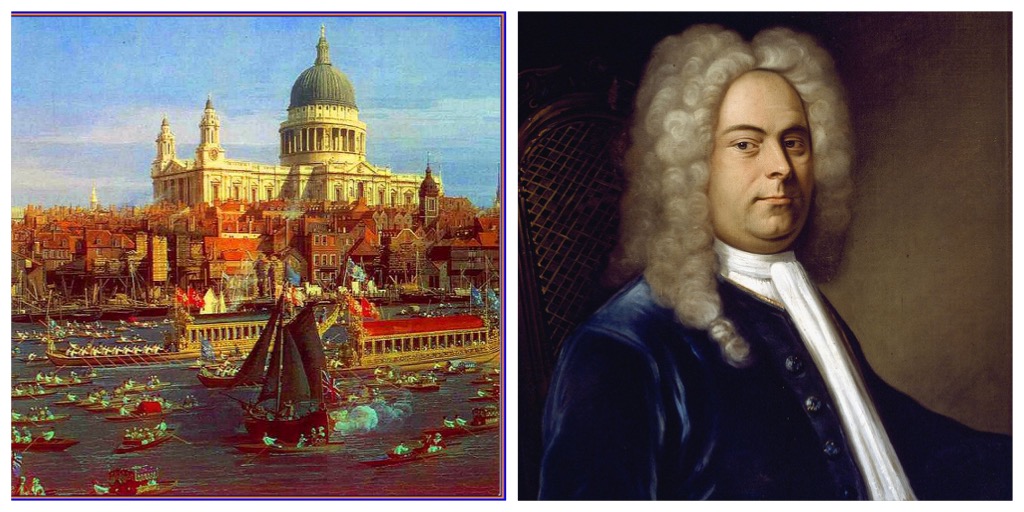

George Frederick Handel

The Water Music: Allegro

English Baroque Soloists

John Eliot Gardner (conductor)

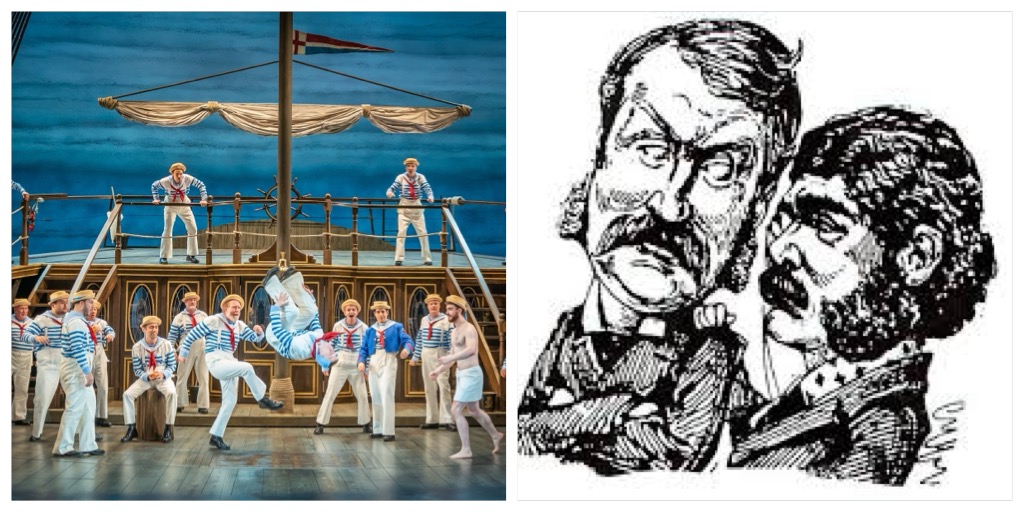

Gilbert and Sullivan

HMS Pinafore: Chorus of Sailors and Relatives

Orchestra and Chorus of Scottish Opera

Richard Egarr (conductor)

Bedrich Smetana

The Moldau

Prague Symphony Orchestra

Libor Pesek (conductor)

Claude Debussy

La Mer :Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea

Montreal Symphony Orchestra

Charles Dutoit (conductor)

Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn once stated that he found most inspiration from natural surroundings such as mountains, open spaces and the sea. He greatly enjoyed his travels throughout Europe, and a walking tour of Scotland in 1829 was no exception. The twenty year old Mendelssohn travelled to the Hebrides Islands, off the west coast of Scotland where he visited Fingal’s Cave. The awesome, sea-level, rock formation he viewed inspired him to write a new type of overture, not drawn from a stage work or opera, but rather a stand-alone piece to be programmed as an overture in a concert hall. Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture is evocative of the sea and the scenery he experienced during his time in the Hebrides and in particular at Fingal’s Cave.

Händel wrote his Water Music for a boating party King George I held in July of 1717. The king put his guests on boats and had them rowed up the river Thames to the King’s house at Chelsea, where he served them dinner at one o’clock in the morning. Later, they all floated back to London, arriving around 4am. A contemporary report recounts: …’at about eight in the evening, the King repaired to his barge. Next to the King’s barge was that of the musicians, about 50 in number . . . but no singers. The music had been composed specially by the famous Händel, a native of Halle, and his Majesty’s principal court composer. The King’s approval was so great that he caused it to be played three times in all; twice before and once after supper, even though each performance lasted an hour.‘

Handel’s Water Music is actually a set of three suites, each one in a different key and using a slightly different orchestra. One of King George I’s last acts before his sudden death in June of 1727 was to sign ‘An Act for the naturalizing of George Frideric Handel.‘

The chorus of sailors in Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta HMS Pinafore is known for its lively and humorous portrayal of life aboard a British naval vessel. The well-known song from this chorus is We Sail the Ocean Blue, where the sailors express their enthusiasm for life at sea and their loyalty to their captain and ship.

The English sense of humour has a taste for satire and parody and mastery of that form of wit is exemplified in the operettas of Gilbert and Sullivan. HMS Pinafore was the fourth of those dramas– and the first real blockbuster– when it opened in London at the Opera Comique in May 1878. It also became a nearly instantaneous success in the US, where, in addition to ‘official’ productions, a wild variety of plagiarized versions, parodies, and slapped-together imitations appeared, much to the discomfiture of Gilbert and Sullivan and their business partner, Richard D’Oyly Carte.

Gilbert’s ability to provide satirical plots and libretti amused audiences, but, as one might expect, did not sit well with the powers of English society, most notably Queen Victoria. While Arthur Sullivan was knighted by Victoria in 1883, with the collaboration still active, Gilbert was not knighted until 24 years later in 1907 by Victoria’s son and successor, King Edward VII

Bedřich Smetana

Bedřich Smetana was a prodigy, turning heads as a promising pianist. He spent three years as live-in piano teacher for a wealthy family, and used his earnings to finance further study of harmony, counterpoint, and composition. By 1851, thanks to a kind word from Liszt, Smetana saw one of his compositions accepted by a publisher. Within a few years he occupied a prominent place in the Czech musical world, as a conductor, a critic, and, increasingly, a composer.

In 1866, he was named principal conductor of the Provisional Theater, where he built an orchestra that included among its ranks the violist—and fledgling composer—Antonín Dvořák. In 1874, he began losing his hearing and within a few months he grew substantially deaf. Although he could no longer perform music, he could still write it so he immediately plunged into composing the first two movements of Má Vlast (My Country). The second movement, Vltava (The Moldau), was composed in nineteen days and its subject is the Bohemian river that flows north through Prague on its way to join the Elbe, which in turn leads its waters to the North Sea.

Ironically, the visual inspiration for La mer came, not from impressionistic painters, but from two earlier generation of painters: Joseph Turner (1775–1851), whom Debussy lauded as the ‘finest creator of mystery in art,’ and Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), whose The Great Wave off Kanagawa print was the composer’s choice to adorn the title page of the score.

Among the artists’ innovations was the use of colour as an end in itself, and among the most influential legacies of Debussy was the use of musical colour as an end in itself. The most obvious way Debussy achieves his sonorities is by augmenting the standard orchestra with some glitter: two harps and a large percussion section. Harmonic changes serve as colour washes; chords dissolve rather than resolve and short melodic motives rather than fully developed themes sparkle in brief solos throughout the piece

Leave a comment