Composers and performing artists can often be superstitious about dealing with the trials and tribulations of performing and composing. From ‘touch wood’ or avoiding walking under a ladder or crossing fingers or feeling concerned about getting out of bed on Friday the 13th. Many of these superstitions can feel very real to those affected by them. In this edition of In Conversation we look at how superstition has impacted on the work of composers and performers.

Tritone – Diabolus in Musica

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990)

West Side Story: Act I: Maria

Jim Bryant

Johnny Green

Triskaidekaphobia, or Fear of the Number 13

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951)

Friede auf Erden, Op.13

Tenebrae

Nigel Short (conductor)

The Cursed Opera

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

La forza del destino / Act 4: “Invano Alvaro…Fratello…” – Live In London / 1995

Leo Nucci

Leone Magiera

Luciano Pavarotti

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

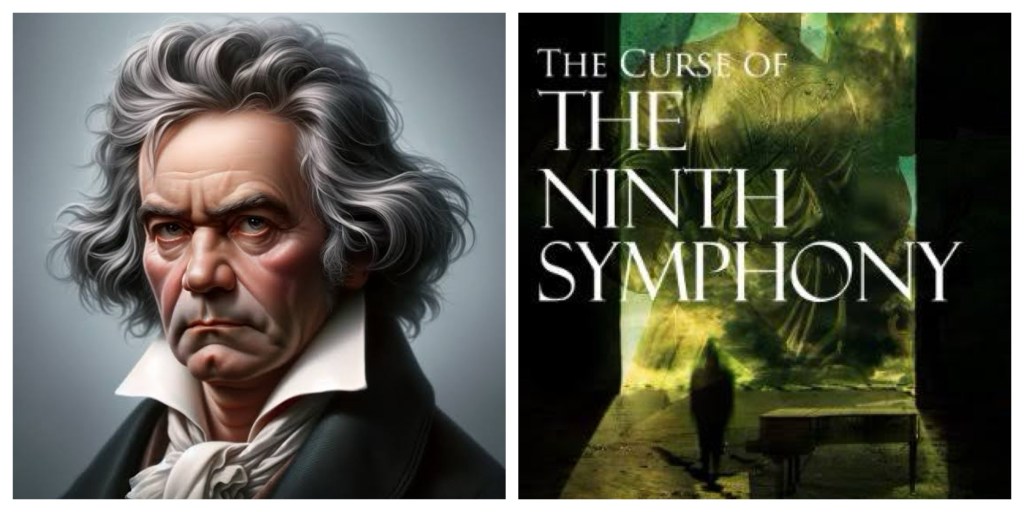

The Curse of the Ninth

Ludwig van Beethoven (1870-1827)

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125 ‘Choral’: IV. Allegro assai

Britten Sinfonia

Britten Sinfonia Voices

Christianne Stotijn, Ed Lyon Jennifer France

The Choir of Royal Holloway

Thomas Adès (conductor)

Tritone – Diabolus in Musica

As early as the Middle Ages, the tritone — two notes a diminished fifth apart — has been referred to as the ‘devil’s interval.’ Vilified by the church who believed the role of music was to praise God through beautiful tones, it was avoided by numerous Medieval and Renaissance composers. Because the tritone is a restless interval and regarded as an unstable interval, the symbolic association with the devil and its avoidance led to Western cultural convention seeing the tritone as suggesting “evil” in music. Later, with the rise of the Baroque and Classical music era, composers accepted the tritone, but used it in a specific, controlled way. It is only with the Romantic music and modern classical music that composers started to use it totally freely, without functional limitations notably in an expressive way to exploit the “evil” connotations culturally associated with it. For example, the climax of Hector Berlioz’s La damnation de Faust (1846) consists of a transition between “huge B and F chords” as Faust arrives in Pandaemonium, the capital of Hell and Leonard Bernstein uses the tritone harmony as a basis for much of West Side Story.

Triskaidekaphobia, or Fear of the Number 13

Friday 13th, for many people around the world, means it’s the unluckiest day of the year. Many hotels are designed without a room numbered 13, testaurants refuse to have a ‘table 13’and some major airlines, including Lufthansa, refuse to have a 13th row. It’s a belief that has been passed down through society for decades, and there are all kinds of theories as to why the day is particularly wretched. The number 13 has been considered unlucky for centuries and throughout history works of literature, entertainment and pop culture have reinforced myths around the number. The date frightened Arnold Schoenberg, for one. The composer, who was famous for his 12-tone compositions, was struck with terror by the number 13 (also known as triskaidekaphobia). Though he was born on the 13th of September in 1874, he spent much of his life avoiding the number when he could. Even his compositions bear this mark: rather than 13, he would label measures in between 12 and 14 as 12a. Strangely or maybe aptly, Schoenberg’s wariness of the number proved well founded. He died on July 13, 1951, at the age of 76 (which any numerologist would see, 7 + 6 = 13). He had spent the day in bed, feeling unbearably anxious and believing the worst was about to happen…and sadly it did.

The Cursed Opera

Many singers say “toi toi toi” to each other before a performance, which is a shortening of the German word “Teufel” (devil) and in saying that it supposed to keep him away. The great tenor Luciano Pavarotti refused to be cast in Verdi’s La Forza del Destino since it was widely considered to be a “cursed” opera. The opera is associated with spooky power outages, sudden illness of a soprano that delayed the initial premier by 12 months and the most tragic of all, on-stage death of the principal baritone Leonard Warren who collapsed right after his Act III aria “morir, tremenda cosa” (to die, a momentous thing) during the 1960 Met performance. La Forza is violent and chaotic, and it flopped on its first run. Part of it has to do with the extremes of the emotion and the abruptness with which they change from comedy to tragedy, to absurdity, to religiosity, to drinking songs, to hate. All in all, in spite of La Forza del Destino being a great opera, it could be one to avoid…

The Curse of the Ninth

There is a superstition within classical music, dating back hundreds of years, known as the curse of the ninth. The superstition states that a composer’s ninth symphony is destined to be their last, with a number of composers dying either while writing their ninth, after completion, or before finishing a tenth. Composers who have fallen prey to the curse include Schubert, Dvořák, Bruckner, and most famously, Beethoven – who after completing his ninth, Ode to Joy, was kissed by the curse before writing a tenth. Gustav Mahler, however, having seen his contemporaries lives taken too soon refused to title his ninth symphony by number, instead choosing to title it, Das Lied von der Erde(“The Song of the Earth”). His attempt to dodge the curse was successful, or so it seemed, when his tenth symphony, which he titled his ninth, was complete. But his victory was short-lived. During the writing process for what would have been his eleventh symphonic work, but titled his tenth, the curse returned. It was in 1911, just two short years after his apparent victory that he died, with the curse taking another victim.

Leave a comment