Music in France around the end of the 19th Century and beginning of the 20th Century is often defined by the music of Debussy and Ravel. However, there were other composers at that time who, stylistically, were heading in another direction. Phil Whelan and I take a look at some of these composers and, unsurprisingly, find some glorious music.

Georges Bizet (1838-1875)

Symphony in C: Movt IV Allegro vivo

Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields

Sir Neville Mariner (conductor)

Jules Massenet (1842-1912)

Thaïs: Meditation

Bomsori (violin)

NFM Wrocław Philharmonic Orchestra

Giancarlo Guerrero (conductor)

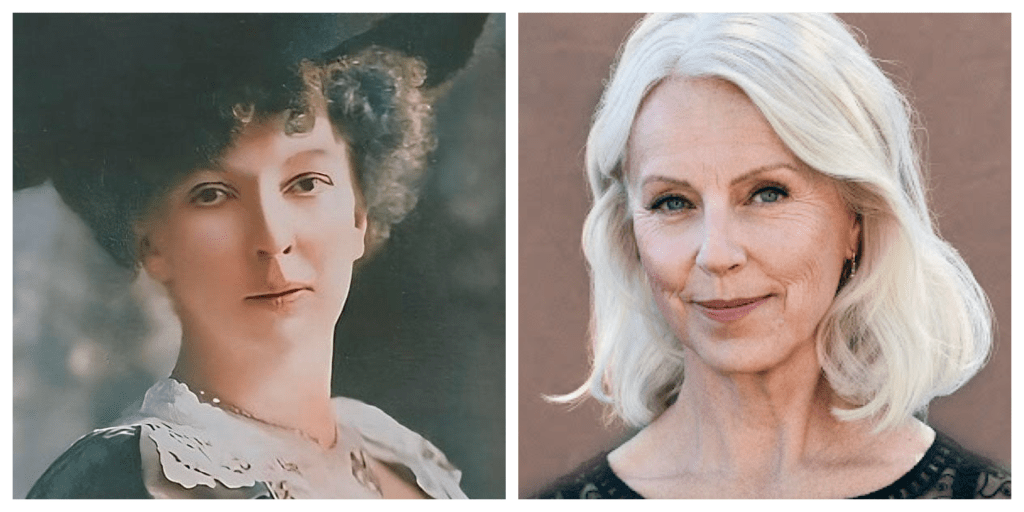

Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944)

When your sky turns golden in the morning lights

Anne Sofie von Otter (soprano)

Bengt Forsberg (piano)

Joseph Canteloube (1879-1957)

Songs of the Auvergne: Bailero

Karina Gauvin (soprano)

Canadian Chamber Orchestra

Raffi Armenian (conductor)

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869)

Overture: The Roman Carnival Op 9

London Symphony Orchestra

Sir Colin Davis (conductor)

Bizet was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire at the age of nine, and wrote his first symphony, the Symphony in C, at the age of seventeen.

The Symphony in C was most likely a student assignment while the young composer was studying at the Paris Conservatoire.

It was never published nor performed in Bizet’s lifetime; in fact, no one knew it existed until nearly eighty years later, in 1933, when it was discovered in the Conservatoire’s archives by a musicologist

The premiere was in Basel, Switzerland in 1933 and has remained a mainstay in the repertoire ever since.

Undoubtedly, Bizet was influenced by his teacher, Gounod, who had just composed his Symphony No. 1 which was premiered earlier in 1855. Bizet was influenced by the structural and stylistic elements of Gounod’s Symphony and, as Gounod was the far more successful and famous of the two, Bizet was concerned that by publishing his first symphony so soon after Gounod, his reputation as a composer could be damaged. Bizet, therefore, never mentioned this work in any of his letters, nor tried to have it published and performed.

Nowadays, the Symphony in C, with its traditional four-movement symphonic structure, is loved for its beautiful melodies, rich orchestration and elegant charm.

Georges Bizet, died four months after the disastrous opening of his most famous work, Carmen, at the young age of 36.

After his death, his work, apart from Carmen, was generally neglected. Manuscripts were either given away or lost.

He founded no school and had no obvious disciples or successors. After years of neglect, his works began to be performed more frequently during the 20th Century and his Symphony in C is now regularly performed in concert halls throughout the world.

Although it is often performed as a concert work, the beautiful strains of the Meditation originate in the opera house as an intermezzo in Massenet’s masterpiece, Thaïs.

The story follows the life of the famed Alexandrian courtesan Thaïs and the monk Athanaël who has come to convince her to renounce her sinful life.

She is driven into hysterics by the monk’s words, seeing emptiness in her life and the approach of old age, until she collapses.

The famous Meditation that follows her collapse musically depicts her conversion to a life of piety. Religious conversion aside, the Meditation is a beautiful melody crafted with extreme delicacy.

It is unsurprising that it has found a place in the repertoire independent of the opera and, though originally for solo violin and orchestra, has been arranged for almost every instrument imaginable.

Massenet is a composer best known for his operas.

His compositions were very popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries winning praise from the likes of Tchaikovsky and Charles Gounod.

Soon after his death, his style went out of fashion and, apart from Manon and Werther, his operas fell into almost total oblivion.

However, since the mid-1970s, many of his operas have undergone periodic revivals.

Although Cécile Chaminade’s piano music has never been entirely neglected, her songs have received little attention, composing over a hundred mélodies for voice and piano as well as an opéra comique.

Like many of her contemporaries, Chaminade’s choice of poems veers towards the sentimental and move back and forth between the romantic, the exotic and the whimsical.

She was, however, a prolific composer who published more than four hundred pieces over her eighty-six years.

These works cover a wide range of forms: concertos with soloist and orchestra, character pieces for solo piano; a symphony and an orchestral suite.

Chaminade’s compositions are tuneful and indicative of the French Romantic vogue in her youth, a time when Saint-Säens was at his peak and the most progressive composers, such as Wagner, were just starting to realize the full potential of the chromatic scale.

She was also an accomplished performer, first making her name by giving recitals of her own music as early as 1878.

Over the next decades, these recitals became international concert tours that saw her perform in Vienna, Belgium and Britain, where she became a favorite of Queen Victoria.

She also toured the United States, where her performances in Carnegie Hall, Symphony Hall, the Academy of Music with the nascent Philadelphia Orchestra, and venues throughout the Midwest inspired hundreds of women to found eponymous musical societies: ‘Chaminade Clubs.’

Yet in spite of her international renown, Chaminade continued to find herself marginalized by the Parisian music world, enjoying more success in the provinces.

To be female and to deal with some of the gender stereotypes was an additional struggle and she was often written off by the critical establishment as a composer of salon music.

Her creative output waned after the turn of the century, despite being the first female composer accorded the title of Chevalier in the Legion of Honor (1913), and her deteriorating health prevented her from touring in the 1920s and ’30s.

After moving to Monaco, she died in 1944 in solitude and relative obscurity.

Cantaloube started writing his Songs of the Auvergne on a train travelling through the southern French countryside in 1923.

The Auvergne is a region in central France, south of Lyon full of hills, forests, valleys and picturesque villages and towns.

The song, Baïlèro, is justifiably a favourite, its gentle woodwind accompaniment forming a backcloth to the shepherdess who beckons the shepherd to cross the river to make love to her.

Baïlèro lèrô lèrô is her seductive entreaty with all three verses set to the same accompaniment.

Joseph Canteloube was born in the Auvergne in 1879, in the town of Annonay, and first encountered the local dances and folksongs as a boy, on long walks through the countryside with his father.

Canteloube believed passionately in the power of folk music to renew and enrich classical music.

He wrote five books of Songs of the Auvergne, over a period of more than 30 years.

The tunes are traditional melodies, and the words are in the local language, Occitan.

He is essentially a composer remembered for only one thing: his settings of the Songs of the Auvergne.

His other works include three orchestral pieces as well as a few pieces of chamber music but the heart of his composition is captured only in the celebrated five books of songs.

Canteloube eventually moved to Paris where he met a whole circle of composers from the regions who to some extent shared his ideals.

He also befriended the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla.

Canteloube himself became an entrenched conservative in the developing picture of French music as it evolved during the 1920s, refusing to follow the frivolous rebellion of Les Six, nor the dissonant language and rhythmic exploits of Stravinsky

One of Berlioz’s great fiascoes was his opera Benvenuto Cellini, a brilliant musical score which, sadly, could not hide an impossible libretto with fatal dramatic flaws.

The premiere at the Paris Opera in 1838 survived for just three performances and an attempt at a revival a few years later failed as well and only its lively overture, using themes from the opera, has survived in the repertoire.

Six years later Berlioz took two of the most fetching musical segments of Act I of Benvenutto Cellini and fashioned from them the Roman Carnival Overture, originally meant as the introduction to the opera’s second act.

The premiere of the overture, under the composer’s baton, was an instant success and had to be encored.

The overture is an orchestral showpiece beloved by orchestra players, especially the brass, who Berlioz freed from its role as mere as accompaniment and choosing to make it the equal of the other orchestral sections.

Indeed, it was only in the last few bars of the overture, with brilliant and unpredictable brass, that Berlioz digress significantly from the original opera theme.

Hector Berlioz was a gifted and innovative orchestrator.

He experimented with new instruments, such as the bass clarinet and the valve trumpet and he virtually put the Cor Anglais on the map as the solo instrument par excellence for conveying musical melancholy.

He was equally innovative in musical form and in stretching the limits of classical tonal harmony.

However, he was a controversial composer, dramatically splitting the opinions of critics.

Ironically, he started out as a medical student but swapped disciplines mid-course, commencing his formal music studies at the Paris Conservatoire in 1826.

An extraordinary pupil, over the next six years he produced a series of increasingly original and inventive works that climaxed in the Symphonie Fantastique.

When his requiem, Grande Messe des Morts, was first performed in 1837, its unprecedented scale – both emotional and instrumental – left onlookers gasping in its wake, while Roméo et Juliette (1839) accomplished much the same reaction in the symphonic sphere.

His greatest masterpiece, the epic five-hour opera Les Troyens, defied all attempts to get a complete production staged in his lifetime, and although his last great work, the light-hearted opera Béatrice et Bénédict, was well received, it was a case of too little too late for Berlioz.

In 1868 Berlioz’s mental and physical health declined rapidly and he died in 1869.

Leave a comment