Composers throughout history have often been affected by conflict and have expressed their feelings the best way they know how. Maurice Ravel, Richard Strauss, Vaughan Williams and Benjamin Britten all composed music to commemorate those who tragically lost their lives. We choose four pieces specifically composed in the aftermath of war and conflict.

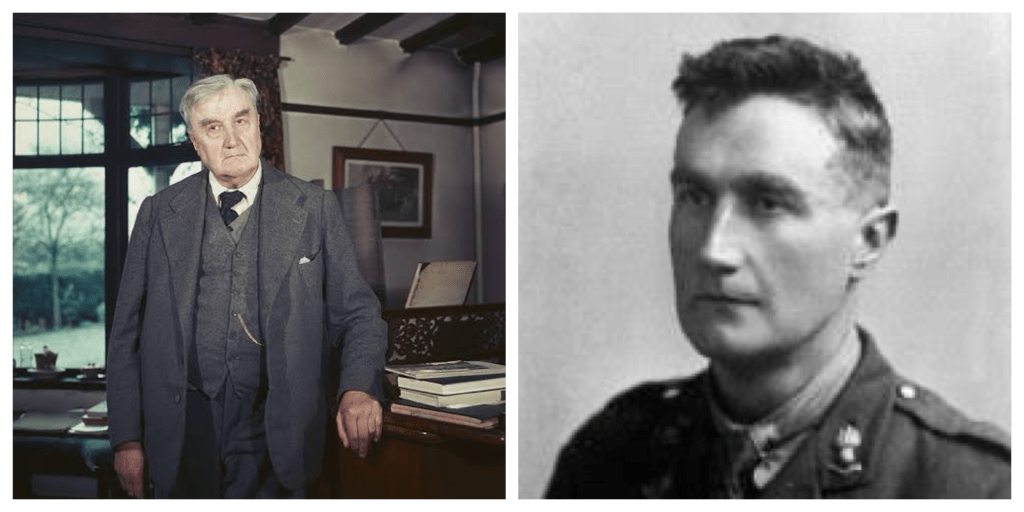

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

Dona Nobis Pacem: Agnes Dei

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

David Hill (conductor)

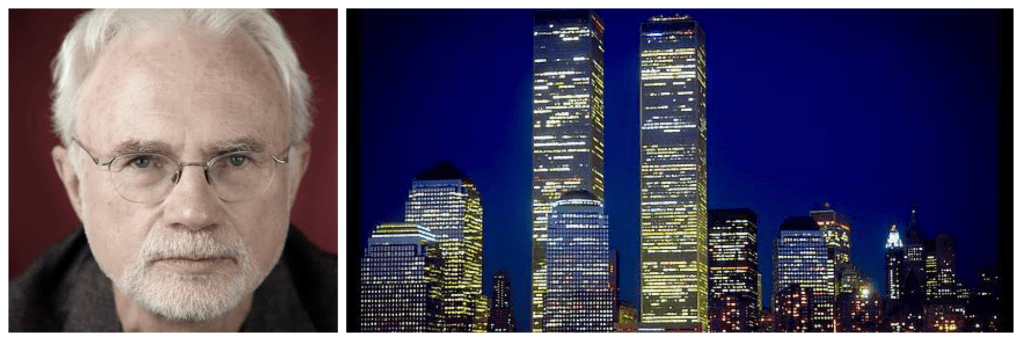

John Adams (b. 1947)

On the Transmigration of Souls (2002)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra

Lorin Maazel (conductor)

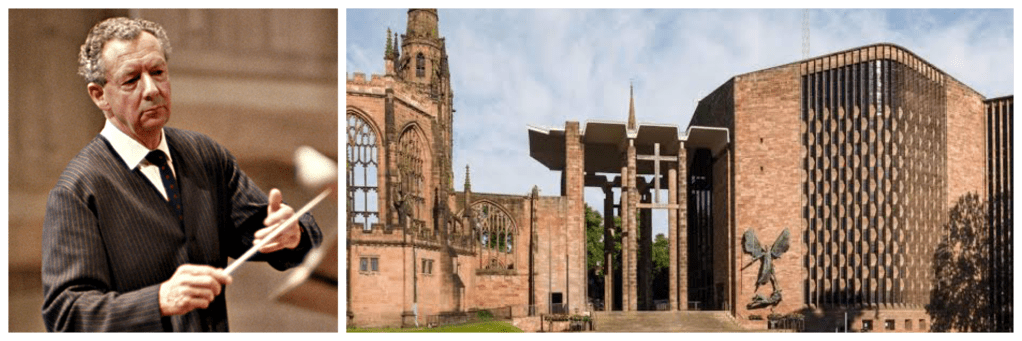

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

War Requiem, Op. 66: v. Dies Irae – Dies irae

London Symphony Chorus and Orchestra

Gianandra Noseda (conductor)

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Symphony No. 7 “Leningrad” (1941)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Leonard Bernstein (conductor)

Ralph Vaughan Williams was intimately familiar with the horrors of war.

When World War I broke out, the 42-year old British composer immediately volunteered for service as an ambulance driver on the front lines, where he witnessed unspeakable carnage.

He served as an artillery officer, and the thundering of the big guns would ultimately destroy his hearing.

Vaughan Williams’ wartime experiences affected him profoundly, shaping his entire view of human nature.

After the war, he grappled with these experiences through his music, seeking to come to terms with all that he had seen and to rediscover his place in civil society.

In 1936, the Huddersfield Choral Society commissioned Vaughan Williams to write a large-scale work in honor of its centennial year. He threw himself into the project, titled Dona Nobis Pacem—Latin for “grant us peace,” a phrase familiar from its use in the traditional Christian Mass—using the opportunity to create a work that would encapsulate his feelings on war, serve as a warning against violence, and implore us to recall the better angels of our nature.

The first performance was given in Huddersfield on October 2, 1936, with Renée Flynn and Roy Henderson as soloists, along with the Huddersfield Choral Society and the Hallé Orchestra conducted by Albert Coates.

It was an immediate success; a month later Vaughan Williams conducted a performance broadcast on the BBC, and the work was performed frequently across Britain over the next 10 years.

The work clearly captured the anxious mood in Britain in the years leading up to the war, and in particular served as a rallying cry for the anti-war movement.

On the eve of the Blitz, the BBC tried unsuccessfully to broadcast the work throughout Germany as a piece of musical propaganda.

During the war itself, dozens of British ensembles performed it across the country to help maintain war-time morale, and assure the population that Britain—and humanity—would survive.

Shortly after its premiere, Vaughan Williams founded the Dorking Refugee Committee to assist victims of Nazi persecution and resettle them in Britain.

During the war he personally escorted Jewish schoolchildren to a safe haven in Surrey, and housed refugees in his own home.

As such it directly foreshadowed, and partially inspired, Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem.

Composers of the 20th and 21st centuries have been less apt than their predecessors to write music specifically in reaction to public tragedies.

Perhaps this is because composers of earlier eras were more bound to a patronage system that obliged them to produce memorial music: Bach, Purcell, and Beethoven were just the pinnacle of a mountain of composers who had to write funeral music for their departed sponsors

Perhaps it is because the management of modern symphony orchestras are less willing to underwrite works that, in the middle of their public mourning, may offend the political sensibilities of the button-down subscribers who sustain most metropolitan orchestras, at least in America.

On the Transmigration of Souls, one of the opening works of the New York Philharmonic’s concert season in 2002, premiered just a week after the first anniversary of the attacks must be one of the first significant works of public mourning commissioned from a major composer in this new century, which may in part be why it won last year’s Pulitzer Prize for music.

It is not programme music meant to recapture the disaster or funeral music meant to formally honor the dead.

Instead, it moves us into an ethereal zone where fragments of dialogue gathered from that terrible day and its aftermath commemorate details of the individual lives of some who died.

After a brief introduction of discovered sounds taped on the streets of New York, a boy’s voice — toneless and detached — repeats the word “missing.”

Gradually other voices begi, a spoken cenotaph, reciting the names of some who died.

As family members recall their dead, the orchestra and chorus swell to a massive, sustained crescendo, the longest, loudest moment Adams has ever composed.

Finally, the music ebbs and the quiet, passionless chanting of the names of the dead begins again.

A fragment of Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question surfaces and then drifts away.

The premiere performance of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem took place on 30 May 1962 at the consecration ceremony for the New Coventry Cathedral.

The original fourteenth-century structure had been destroyed in a World War II bombing raid,

Including the organ, famous for its long history, back to the time when Handel played upon it.

The German Luftwaffe reduced much of the city of Coventry to rubble and the Cathedral although it held no strategic importance, was solely targeted to demoralise the British people.

On the morning after the bombing raid, the decision was made to rebuild the cathedral.

A design competition was initiated and the contract went to the Scottish architect Basil Spence, known for designing the Sea & Ship pavilion on London’s South Banks.

Not everybody was enthusiastic, but the Cathedral ingeniously incorporates the remains of the original in a modernist design.

It took 16 years to finish the project, and the final structure was completed in May 1962.

With Queen Elizabeth II scheduled to attend the consecration of the new cathedral, it was clear that the music had to play a major part in the celebrations.

A number of composers were considered for the commission, but in the end, the honour went to Benjamin Britten, who was Britain’s most internationally recognised composer.

He selected the text of the Latin Requiem Mass, with individual sections would interspersed with nine poems by the First World War poet Wilfred Owen.

Britten divides the musical forces into three groups that alternate and interact with each other throughout the piece.

Only at the end of the last movement are all forces fully combined.

The War Requiem ends with words of peace, and at the head of the score Britten inscribed the solemn words with which Owen prefaced his poems:

My subject is War,

and the pity of War.

The poetry is in the pity.

All a poet can do is warn.

Dmitri Shostakovich embodied two strikingly different personas.

There was the public Shostakovich, the man always navigating the treacherous waters of life under Stalin, and there was the private Shostakovich, a sort of tragic figure, simultaneously cowed and defiant.

Few works in Shostakovich’s output demonstrate the composer’s double life better than his Leningrad Symphony.

It is filled with equivocation, a prime example of Shostakovich walking the fine line between public expectations and his private feelings.

The Germans invaded Russia on June 22, 1941, and, by the end of July, Leningrad, the capital, was completely surrounded.

The siege would last nearly 900 days, during which roughly a million of the city’s residents died, much of the city itself was reduced to rubble, and living conditions for those who didn’t die were ghastly.

Shostakovich composed the first three movements during the summer of 1941 in the midst of the besieged city.

He and his family were evacuated that autumn, and he completed the Symphony in Kuibyshev, the provisional Russian capital, on December 27 of that year; it premiered there on March 5, 1942.

According to an interview with Flora Litvinova, the composer’s friend and neighbour in Kuibyshev, in Elizabeth Wilson’s Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, Shostakovich conceived the “Leningrad” as a work about the struggle against fascism, but not just in its Nazi form.

The finale of the symphony resembles the “invasion” section of the first movement and in masterly fashion, Shostakovich begins things with the temperature low and the power kept in check. The movement builds, over its course, with the composer momentarily relaxing or ratcheting up the tension, to a massive, C-major restatement of the Symphony’s opening theme.

It is music that burns with a flame of defiance, and its power lies not in its human scale, but in its outsize grandeur and weighty eloquence.

Leave a comment