The great 19th century French composer Hector Berlioz holds a unique place in musical history. Far ahead of his time, he was one of the most original of great composers, but also an innovator as a practical musician, superb conductor, a writer and critic whose literary achievement is hardly less significant than his musical output. Few musicians have ever excelled in all these different fields at once.

Messe solennelle, H. 20a: IX. Resurrexit (Original Version (1824)

Monteverdi Choir

Orchestra Révolutionnaire et Romantique

Sir John Elliot Gardner (conductor)

Harold in Italy, Op. 16: IV. Orgie des brigands (1834)

William Primrose (viola)

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Charles Munch (conductor)

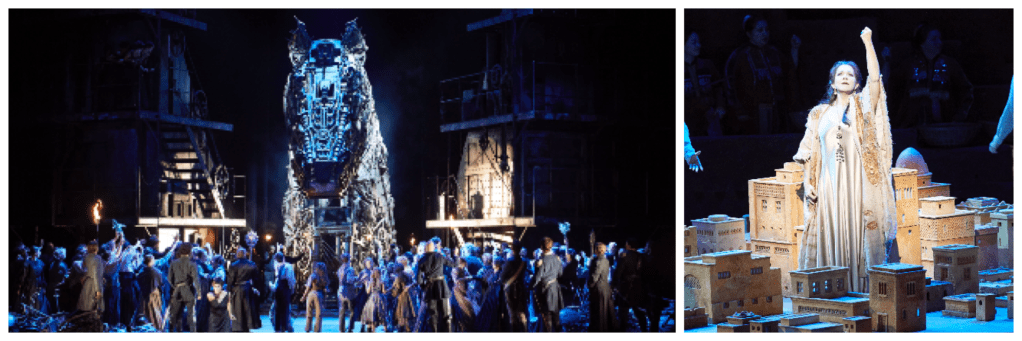

The Trojans, Op. 29, H. 133, Act 1: “Ha ! ha ! Après dix ans passés dans nos murailles” (Un Soldat, Chorus) (1856-1858)

Choir and Orchestra of Strasbourg Philharmonic

John Nelson (conductor)

Béatrice et Bénédict / Act 2: Le vin de Syracuse (1860-1862)

Choir and Orchestra of the Orchestre de Paris

Daniel Barenboim (conductor)

Symphonie fantastique, H 48: V. Songe d’une nuit de sabbat (1830)

Philharmonia Orchestra

Essa Pekka Sallinen (conductor)

Born in a village about 35 miles (56 km) northwest of Grenoble, Berlioz received his education from his father, a doctor, who gave him his first lessons in music At this stage in his life he received very little formal training but Berlioz taught himself the elements of harmony and by 12 years he was composing for local chamber-music groups. He also learned to play the flute and the guitar, becoming a virtuoso on the latter. In 1821 his father sent him to Paris to study medicine where he obtained his first degree in science. However, Berlioz took every opportunity to go to the Paris-Opéra, in which the works of Gluck had for him the most appeal. Eventually, he was accepted as a pupil of Jean-François Lesueur, professor of composition at the Paris Conservatoire which caused disagreements between Berlioz and his parents that embittered nearly eight years of his life. During his Paris years Berlioz was particularly productive, composing an oratorio, numerous cantatas, two dozen songs, a mass, part of an opera, two overtures, a fantasia on Shakespeare’s Tempest, eight scenes from Goethe’s Faust and the Symphonie fantastique. Another success came when in 1830 he won the Prix de Rome. Berlioz was required, under the terms of his prize, to spend three years abroad, two of them in Italy where he met Mikhail Glinka and made a lifelong friend of Mendelssohn. Unfortunately, he was impatient with life at the Villa Medici in Rome so he returned to France after 18 months and forfeited part of his prize.Berlioz wrote his Messe Solennelle in 1824 and was his first large-scale work for chorus and orchestra. He was 20 years old at the time and a student in Paris. Berlioz said he had burnt the score because he gradually started to have doubts about the quality of the work. However, the manuscript of Messe Solennelle was found in 1991 in a wooden chest on the organ platform of a church in Antwerp. Antoine Bessems (1806-1868), a violinist and composer knew Berlioz well and it is possible that the manuscript was given to him by way of thanks and/or recompense for his services. After the death of Antoine the manuscript of the Messe Solennelle came into the hands of his brother Joseph Bessems (1809-1892) who was connected to the St. Carolus-Borromeus Church as conductor.

Harold in Italy, Op. 16 is a symphony in four movements with viola solo composed by Hector Berlioz in 1834. Berlioz wrote the piece on commission from the virtuoso violinist Niccolò Paganini, who had just purchased a Stradivarius viola. Paganini found the piece to be insufficiently flashy for his own performance, and never played it, though he admired it and paid the agreed fee. Berlioz’s idea was to write a series of scenes for the orchestra in which the solo viola would be involved as a more or less active character, always retaining its own individuality. By placing the viola in the midst of recollections he had of his wanderings in the Abruzzi, he wished to make the viola a kind of melancholy dreamer after the manner of Byron’s Childe Harold. Thus the title: Harold in Italy. The four movements are named: Harold in the Mountains, The March of the Pilgrims Singing Their Evening Prayer, Serenade and for the final movement, Berlioz turns to a more-animated episode, The Orgy of the Brigands. Even amid the tumultuous action, he recalls the earlier scenes, with musical echoes of the previous movements. Berlioz’s contemporaries similarly didn’t know what to make of Harold in Italy and were unsure whether it was a symphony, a tone poem or a viola concerto.

Berlioz’s passion for Shakespeare combined with his love of classical antiquity would be sure to produce something new and splendid. By July 1856 The Trojans had assumed such urgency in Berlioz’s life that the entire mammoth work, orchestration and all, was completed by April 7, 1858. But Virgil was not Berlioz’s only inspiration. His first encounters with Shakespeare, at the hands of an English theatrical troupe visiting Paris in 1827, had been inextricably intermingled with his passion for the actress Harriet Smithson, whom he later courted and married—unhappily, unfortunately. The Trojans is filled, too, with a love of Italy – the landscapes, people, and art, that Berlioz acquired during his 15 months of residence there after winning the Prix de Rome in 1830. Whatever grim fate Berlioz anticipated for his work, the reality proved to be worse. After keeping Berlioz dangling for three years the management of the Paris Opera finally turned it down and he accepted an offer from the Théâtre Lyrique. Chief among numerous indignities was the demand that he divide his opera into two parts, of which only the second, comprising the last three acts and christened Les Troyens à Carthage, was eventually performed, on November 4, 1863. The reception was not unfavourable – enough to sustain 21 performances – but the mutilations practised during the run outraged the composer, especially as they were also incorporated into the printed score. Only in 1890, two decades after the composer’s death, an integral version, sung in German, was presented at Karlsruhe under the direction of Felix Mottl. After decades of neglect, today the opera is considered by some music critics as one of the finest ever written.

Béatrice et Bénédict Berlioz’s last composition is a neo-classical comic opera and the third and final work in Berlioz’s Shakespeare-inspired works, following the choral symphony Roméo et Juliette and the cantata La mort de Cléopâtre. Berlioz almost certainly never saw Much Ado About Nothing, but as early as 1833 he asked a friend to lend him a copy, as he planned ‘a very merry Italian opera’ on the subject. The opera reached its final form in 1863, nearly thirty years after its conception. It’s a joyful and comedic interpretation of Shakespeare’s play, where love and wit take centre stage. Berlioz wrote the libretto himself making some creative cuts and adaptations, streamlining the plot to keep the focus on the central couple and their entertaining verbal sparring. At the heart of the opera is the witty banter between Béatrice and Bénédict, who are both stubbornly opposed to love and marriage. Their sharp-tongued exchanges and reluctant romance make this opera one of the most charming and comedic in the repertoire. Unlike many operas that thrive on dark plots and sinister characters, Béatrice et Bénédict has no villain. Instead, it’s driven by misunderstandings and banter, with the stubborn lead couple providing all the drama.

At the end of his life his unusual music was unloved and unplayed; a widower two times over, he was lonely, and hated people more than ever. He felt wronged by the public and his fellow composers. he was incapacitated by illness and saddened by many deaths. His first wife died in 1854; his second wife, Maria Recio died suddenly in 1862 and his son, Louis, who was a sea captain, died of yellow fever in Havana at the age of 33. Berlioz had faith that his time would come, though. By his estimate, things would pick up for him if he could just live to 140. He made it to 65. After his death, in 1869, some of his works, like the Symphonie Fantastique became firmly entrenched in the canon. The first performance of Symphonie Fantastique took place on December 5 1830 in Paris. It was the composer’s earliest big orchestral work composed when he was not yet 30. Audiences welcomed this piece from the start and it remains his most famous. Hector Berlioz won the heart of Harriet Smithson, whom he had never met, with a concert including the Symphonie fantastique, for which she had unknowingly served as inspiration when the composer fell hopelessly in love with her some years before. The two met the next day and were married on the following October 4. The unfortunate but true conclusion to this seemingly happy tale is that Berlioz and his “Henriette,” as he called her, were formally separated in 1844. The symphony tells the story of a young artist who falls in love with a woman, proceeds to overdose on opium, murders the woman and foresees his own execution There are shepherds and a satanic orgy to help complete the romantic mood. The work looks back to Beethoven’s evocative Pastoral Symphony, yet ahead to Wagner’s leitmotif-driven operas, to tell a story of unrequited love and opium-induced hallucination. The object of the artist’s affection is represented by a musical cue that Berlioz called the idée fixe; it recurs throughout the movements, which flow from a ball to a field, to the guillotine and a hellish witches’ Sabbath. Just about every work of Berlioz defies conventional analysis. His idiosyncratic music didn’t truly catch on until the mid-20th century, and even then fitfully. His operas, even to this day, remain too difficult to stage regularly, and many of his concert works are too strange to program or market to audiences. The Belgian composer César Franck once said that Berlioz’s whole output is made up of masterpieces. Before 1945 the Berlioz repertoire was limited to the Symphonie fantastique and a few brief extracts but with the advent of LPs and CDs the situation radically changed. Audiences can now judge the interpretations that they are being given, and thus they hear Berlioz performances with a knowledge and critical attention comparable to those with which they hear other composers

Leave a comment