Prokofiev is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century. He created seven completed operas, seven symphonies, eight ballets, five piano concertos, two violin concertos, a cello concerto, a symphony-concerto for cello and orchestra, and nine completed piano sonatas. Eventually denounced in Central Committee resolutions drawn up by arts commissar Andrei Zhdanov, Prokofiev continued to compose until his death – on the same day as Stalin – which went unreported for a week.

Piano Concerto No 1 in Db Major Op 10 III: Allegro Scherzando (1911-1913)

Viktoria Postnikova (piano)

Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra

Gennady Rozhdestvensky (conductor)

Symphony No. 1 in D Major, Op. 25 “Classical Symphony”: IV. Finale. Molto vivace (1916-1917)

Chamber Orchestra of Europe

Claudio Abbado (conductor)

Peter and the Wolf, Op. 67: XV. The Procession to the Zoo

Sophia Loren (narrator)

Russian National Orchestra

Kent Nagano (conductor)

Cinderella, Op. 87: Act III: No. 40. First Galop of the Prince – Presto (1940-44)

Moscow RTV Symphony Orchestra

Gennady Rozhdestvensky (conductor)

The Meeting of the Volga and the Don, Op. 130

Philadelphia Orchestra (1951)

Ricardo Muti (conductor)

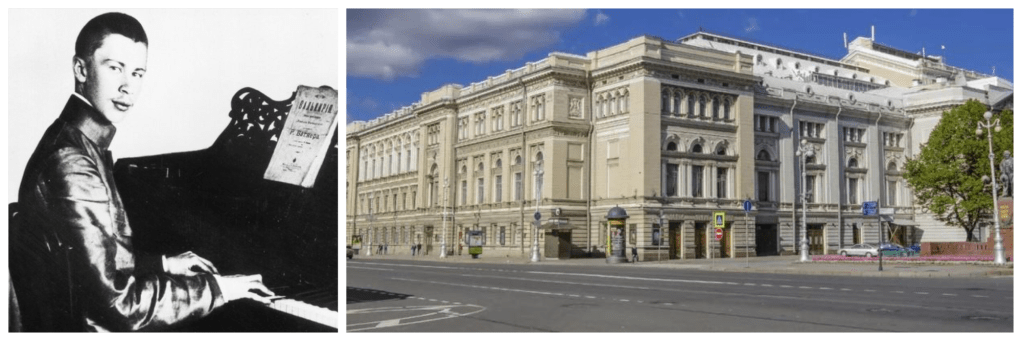

Prokofiev was born into a family of agriculturalists so village life, with its peasant songs, left a permanent imprint on him. His mother, a good pianist, became Prokofiev’s first mentor in music and arranged trips to the opera in Moscow. Reinhold Glière twice was Prokofiev’s first teacher in theory and composition and prepared him for entrance into the conservatory at St. Petersburg. The years Prokofiev spent at that institution—1904 to 1914—were a period of swift creative growth. He studied the compositions of Igor Stravinsky, particularly the early ballets and was attracted by the work of modernist Russian poets and by the paintings of the Russian followers of Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso.

Whilst still studying at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, the 22-year old Prokofiev, entered a piano concerto competition in 1912 and performed one of his own pieces hoping to win a grand piano and the Rubinstein Award. The gambit worked and he took the grand prize. The composer had premiered his first concerto a few months earlier in Moscow and in both situations the critical response was mixed. Some judges wanted to throw the kid out for such a brazen move and some critics thought the piece was a lot of noise. But no one could deny the lightning fingerwork of the young man on the bench as the Piano Concerto in D-flat was a clear showcase for the performer-composer.

In the final movement, passion and intensity increase steadily as the soloist gains energy and the orchestra is invited to offer background surges. Eventually the soloist repeatedly launches dazzling passages which soar and land in the high registers. At the close we find the soloist wistfully declaiming the opening subject, now decorated with swirling trills on each note, bringing the concerto to an exciting conclusion.

At first, Prokofiev was not overly troubled by the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in February 1917. For the most part, musical life continued undisturbed, and Prokofiev composed, practised and went to concerts and rehearsals as before. Shortly after his 26th birthday in April he settled in an idyllic farm just outside the capital. It was during his stay at the farm that he would compose one of his best-loved works, his “Classical” Symphony. Prokofiev composed without a piano which was seen as a crutch; the true master was supposed to be able to compose everything in his head. More significant, however, was his overall approach to the symphony. In an era when symphonies were often sprawling, emotionally wrought works, Prokofiev decided to subvert expectations by composing his first symphony along Mozartian lines. It would be concise and playful, updating traditional classical forms with modern harmonies, rhythms and orchestral colours.

Throughout, Prokofiev wittily juxtaposes his own musical language with typical melodic turns and gestures from Mozart’s time. With its impish sense of humour, impeccable craftsmanship and charming melodies, the symphony was a breath of fresh air, and it has remained one of the composer’s most popular works. Prokofoiev composed a finale, lively enough for there to be a complete absence of minor triads in the whole movement, only major ones. Featuring virtuoso parts for flutes and oboes, this sparkling finale brings the symphony to a breathless ending. Prokofiev finished the symphony in September 1917, and the premiere was scheduled for November 4. It had to be rescheduled, however, due to the Bolshevik coup in October. Back in Petrograd, he met with the new People’s Commissariat for Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky, in order to obtain permission to go abroad. A few weeks later he was on the Trans-Siberian railroad headed to Vladivostok. From there he would travel by way of Japan to the United States, where he would try to make his name in the new world

Although he enjoyed material well-being, success with the public, and contact with outstanding figures of Western culture, Prokofiev increasingly missed his homeland. Visits to the Soviet Union in 1927, 1929, and 1932 led him to conclude his foreign obligations and return to Moscow once and for all. From 1933 to 1935 the composer gradually accustomed himself to the new conditions and became one of the leading figures of Soviet culture. His work in theatre and the cinema gave rise to a number of charming programmatic suites: Lieutenant Kije suite (1934), Egyptian Nights suite (1934) and Peter and the Wolf (1936).

By the mid-1930s, Prokofiev was already a notorious composer, respected among artists but not altogether celebrated trusted by the regime of Josef Stalin. His music, which incorporated harsh dissonance and unusual structures, had at times pushed the prescribed standards of the Soviet committee. This tension dated back at least to 1915, when a Moscow critic published a scathing review of the composer’s Scythian Suite — despite the fact that the performance had been cancelled and the composer remained in possession of the score’s only copy. Likely, his international reputation protected him to a degree. Where other artists were being censored (or much worse: in 1940, the premiere of an opera by Prokofiev was postponed because Stalin’s secret police had arrested and shot the director), Prokofiev navigated the politics of the time in such a way that he could continue composing mostly what he chose.

In 1935, Prokofiev, his wife and children attended a performance at the Moscow Children’s Theatre of a fanciful opera titled The Tale of the Fisherman and the Goldfish. Spotting an opportunity, the theatre’s director, Natalia Satz, suggested to Prokofiev that he compose a piece of music for children that told a story while also introducing the audience to different instruments. The composer took the suggestion to heart and began work. Once occupied, Prokofiev only took a few days to turn out the piece we now know as Peter and the Wolf. It is, today, Prokofiev’s most widely and oft- performed composition. The story of Peter and the Wolf is relatively straightforward as told by the narrator; the brilliance of the work comes in its characterful depictions of the various animal and human characters: Peter is told by the strings, the wolf – ominous and strong – is depicted by three horns, Peter’s grandfather by the bassoon and Peter’s cat by the clarinet. A bird is represented by the flute, a duck by the oboe and the hunters by the ominous combination of timpani and bass drum. It all makes for a vivid fantasy that feels at times like a film score yet ultimately needs no visuals to convey the colourful story.

Prokofiev’s work in 1941 on the ballet Cinderella jostled with other events and distractions – professional, personal, and global. His marriage to Lina was at a breaking point: He was uncertain about the viability of his illicit relationship with Mira Mendelson, his new opera Betrothal at a Monastery was in production and last, but certainly not least, there was a war going on. The fantastic (and surprising) success of Romeo and Juliet had encouraged the Kirov Ballet to commission the new work in 1940, but Prokofiev wouldn’t complete the project until 1945. His busy, complicated life continued to intervene during those four years, as did the collapsing world order.

The first two acts of Cinderella were composed during the dissolution of Prokofiev’s marriage to Lina and the start of his public life with Mira. But Prokofiev was working on an autobiography during that same 1941 summer, so it seems likely the reflective mood engendered by that process found its way into Cinderella. Both the ballet and the memoir had to be shelved when Germany invaded, however, and Prokofiev soon turned his attention to an opera based on Tolstoy’s War and Peace. He and Mira were able to return to Moscow in 1943 and he got back to work on the ballet in due course, reckoning at last with his own delayed midnight and completing the orchestration in 1944. When the premiere finally happened in 1945 it was at the Bolshoi, not the Kirov, but the commissioning company got its turn just one year later (with a production the composer greatly preferred). Three orchestral collections were drawn from the score in 1946.

History of music is filled with musicians and composers who fled oppression for safer environs. But there was a small subset of prominent musicians who remained firmly entrenched in the cultural life of these regimes, and they are often the figures that are the subject of some controversy (the obvious archetype being Wilhelm Furtwangler). Sergei Prokofiev was one such figure. When Prokofiev returned to the Soviet Union permanently in 1936 this meant dealing with Stalin’s government, the Union of Soviet Composers and the Zhdanov Decree, (In 1948 Zhdanov denounced composers including Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev as formalists, effectively ending the Prokofiev’s career). This caused turbulence in Prokofiev’s last decade and a half as a composer. Like Shostakovich, it required a delicate dance of appeasement and frustration, toeing the party line and unleashing your innermost feelings in deeply hidden musical codes. Prokofiev’s toes were firmly in line for the last orchestral composition he wrote. It was a celebration of the canal joining the Volga and Don rivers, an endeavor that had been in that theoretical planning stage for centuries. The premiere took place in late February 1952 about three months before the canal actually opened, and the audience was treated to what Prokofiev dubbed a “Festive Poem” with the mysteriously cryptic title The Meeting of the Volga and the Don. It is perhaps disingenuous to say that this piece compares favourably to Prokofiev’s greatest works, but what it lacks in refinement and technical mastery it more than makes up for in sheer entertainment and brute force. At times it borders on film music (as music for a state function would have needed to sound), but it still has many characteristic Prokofiev-isms, not the least of which is the always fascinating use of colour, texture, and contrast.

Leave a comment