Aaron Copland is regarded as a pioneering figure in American music. His eclectic compositional style covered neo-classicism, popular music, European nationalist traditions, jazz folk music, and the 12-tone idiom. For the better part of four decades, he composed operas, ballets, orchestral music, band music, chamber music, choral music, and film scores. He was a teacher, writer of books and articles on music, organiser of musical events, and a much sought after conductor and worked tirelessly to promote other composers, at Harvard, Tanglewood and on radio and television

Ballet: Grohg V. Imagined the Dead are Mocking Him (1922-25)

Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Leonard Slatkin (conductor)

El Salón México (1932-36)

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra

John Wilson (conductor)

The Promise of Living (1954) from The Tender Land

Tanglewood Festival Chorus

Boston Pops Orchestra

John Williams (conductor)

Symphony No 3 IV. Molto deliberate (Fanfare) (1944-46)

San Francisco Symphony Orchestra

Michael Tilson Thomas (conductor)

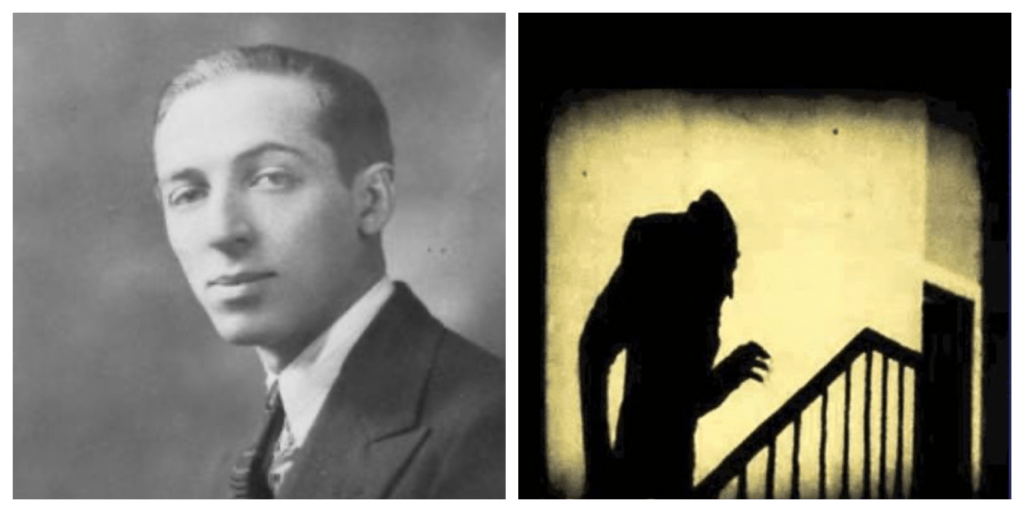

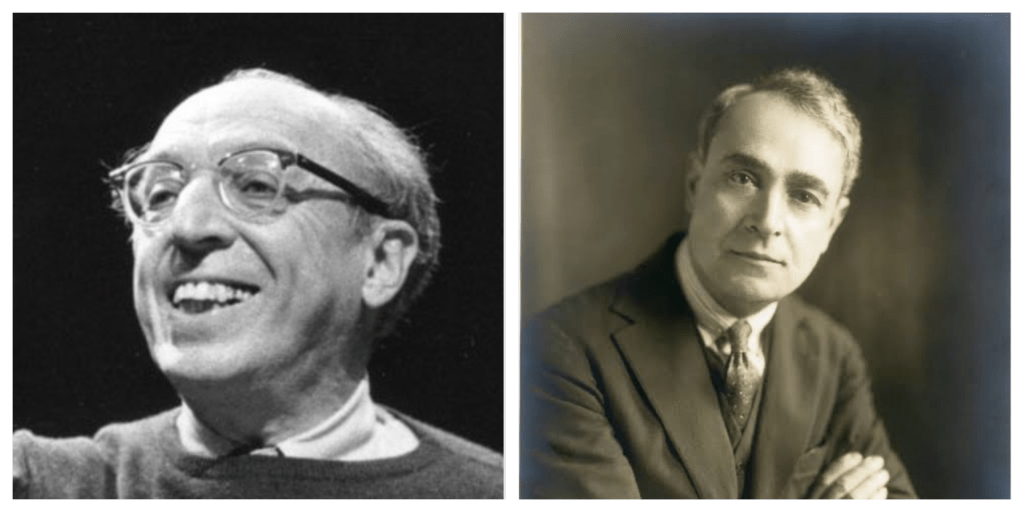

The son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, Copland was born in New York City and attended public schools. An older sister taught him to play the piano, and by the time he was 15 he had decided to become a composer. In the summer of 1921 he travelled to Paris and came under the influence of Nadia Boulanger, a brilliant teacher who shaped the outlook of an entire generation of American musicians. Among her students were many important composers, soloists, arrangers, and conductors including Lennox Berkeley, Elliott Carter, Philip Glass, Quincy Jones and Daniel Barenboim.Coplnad decided to stay on in Paris, where he became Boulanger’s first American student in composition. It was in the early 1920s when Copland was in Paris that he started to write his first orchestral music. He and his roommate, the writer, director and critic Harold Clurman, went to the movies. Silent movies, of course. Inspired by what they saw, Copland decided to write a ballet if Clurman would write the scenario. The movie that inspired them was F.W. Murnau’s 1922 horror classic Nosferatu. Murnau’s film was an unauthorised adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula and after a court fight, the Stoker heirs won their lawsuit about rights, and the court ordered all copies of the film were to be destroyed. Luckily, some copies did survive, which is how we know it today. The music was intended to be morbid and excessive, meeting the taste of the time for the bizarre. Copland also took the opportunity to use much more modern rhythms and dissonances than he had before in his need to provide gruesome events for the ballet. After playing the work with Nadia Boulanger arranged for piano four-hands at a party in 1924, Copland put the work away and did not release it for publication. He did arrange one section of the introduction, the Cortége macabre, for Howard Hanson, director of the Eastman Philharmonic, but Copland withdrew the work from his catalogue in 1927 but reinstated it at Hanson’s request in 1971. Copland’s repressed score was found again in its 1932 revised version in the 1990s by English composer Oliver Knussen and it received its first orchestral performance in 1992.

The ballet was devised in 6 sections:

1. Introduction and Cortège

2. Dance of the Adolescent

3. Dance of the Opium-Eater (Visions of Jazz)

4. Dance of the Street-Walker

6. Illumination and Disappearance of Grohg

The fifth section, entitled Grohg Imagines the Dead Are Mocking Him sees Grohg beginning to hallucinate and he imagines corpses are making fun of him and violently striking him. Nevertheless, he joins in their dances and chaos ensues, with Grohg eventually raising the street-walker over his head and throws her into the crowd. It’s Copland the consummate composer, but not on a theme or in a sound that we know him for today.

After three years, Copland returned to New York City with an important commission: Nadia Boulanger had asked him to write an organ concerto for her American appearances.

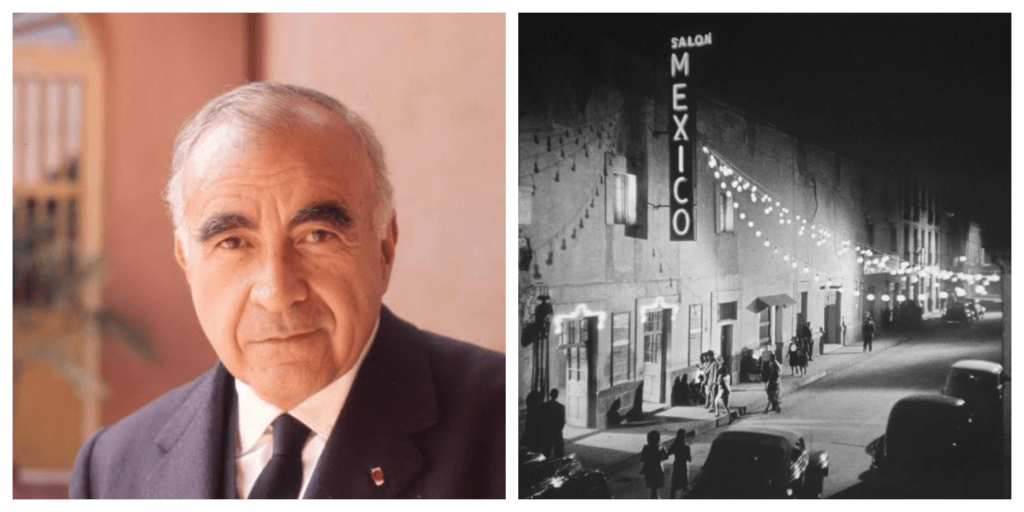

That season the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra had its premiere in Carnegie Hall with the New York Symphony under the direction of the composer and conductor Walter Damrosch. He also worked with jazz elements in Music for the Theater (1925) and the Piano Concerto (1926). There followed a period during which he was strongly influenced by Igor Stravinsky’s Neoclassicism, turning toward an abstract style in compositions such as the Piano Variations (1930), Short Symphony (1933), and Statements for Orchestra (1933–35). Around this time, eager to entice his friend and fellow composer to visit Mexico, Carlos Chávez made Aaron Copland a tempting offer in 1932: an all-Copland concert at the National Conservatory. Copland took the bait. Together with his boyfriend, a violinist named Victor Kraft, Copland drove from New York to San Antonio, where they boarded a train for Mexico City. Copland’s interest in Mexico, however, went beyond the opportunity of hearing his works performed. With its vibrant new artistic life, Copland was eager to see post-revolutionary Mexico with his own eyes. He was not disappointed and Copland and Kraft would stay for four months. One place in particular captured the composer’s imagination: El Salón México, a ‘Harlem type night-club’ with “three halls. He fell in love with the establishment, staying until closing at 5 a.m. on at least one occasion. Copland soon resolved to write a piece about the Salón and for inspiration he drew, not on the popular dance music he heard at El Salón, but on traditional Mexican folk songs. Stylistically, El Salón México marked a turning point for Copland. Like many left-leaning artists and intellectuals, Copland became increasingly concerned with the artist’s relationship to society during the Great Depression; he wanted to write music for “the people” that would make use of the many innovations of modern music while still remaining accessible to ordinary listeners.

Furthermore, he wanted to write music that was distinctly American. El Salón México would be among his first and most successful works in this new, populist style. It would take years for this piece to reach its first performance, however but proved successful with musicians, audiences, and critics alike. It remains one of Copland’s most popular works which he dedicated to Kraft. Copland put his final touches on the piece in 1936, and Carlos Chávez led the premiere with the Orquesta Sinfónica de Mexico in 1937.

There occurred a change of direction that was to usher in the most productive phase of Copland’s career. After the 1930s, Copland attempted to simplify his new music in order that it would have meaning for a large public. The decade that followed saw the production of the scores that spread Copland’s fame throughout the world. Most important of these were the three ballets based on American folk material: Billy the Kid (1938), Rodeo (1942), and Appalachian Spring (1944; commissioned by dancer Martha Graham). Typical too of the Copland style are two major works that were written in time of war – Lincoln Portrait (1942), for speaker and chorus, on a text drawn from Lincoln’s speeches and Letter from Home (1944). The Promise of Living (1954) from The Tender Land was composed between 1952-1954. It was the classic American songwriting team of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II who commissioned Copland to write a piece in celebration of the 30th anniversary of the League of Composers, an organisation founded in 1923 to champion the work of American composers. Aaron Copland, creator of so many masterful orchestral works, also wrote beautifully for the voice, particularly in his captivating (1954). Copland originally intended his opera, The Tender Land, for television, but NBC Opera Theater rejected it. The New York City Opera premiere was unsuccessful, leading Copland to significantly revise the work over the next year. Since then The Tender Land has been a staple of smaller opera companies throughout America. The music is entirely accessible and makes a direct appeal to the heart, as do the characters’ direct, unfettered emotions.

Copland wrote his Symphony No. 3 on a 1944 commission from the Koussevitzky Foundation at Serge Koussevitzky’s request for the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s 1946-47 season. He wrote the first movement in 1944, the second in summer 1945, and the third in fall 1945. The finale, incorporating the composer’s Fanfare for the Common Man, was written in summer/fall 1946—interrupted by his teaching duties at Tanglewood. Koussevitzky led the premiere with the BSO in Symphony Hall on October 18, 1946, toured it to New York and Pittsburgh, and repeated it in Boston in December. Despite receiving the New York Music Critics Circle Prize for the best orchestral work by an American composer during the 1946-47 season and now frequently hailed as the greatest American work in the genre, Copland’s Third Symphony was disparaged as “false” by one of his greatest allies, composer-critic Virgil Thomson, shortly after its premiere. It was the last time Copland ever used the appellation “Symphony” for a musical composition. Symphony No. 3 was actually the fourth piece he had composed with the word “symphony” in its title, and the only one to bear a numeric designation from its inception. The Symphony for Organ and Orchestra, a hybrid symphony-concerto from 1924, was his earliest. In 1928, Copland created an alternate version without organ, designating it Symphony No. 1. After finishing the Third, Copland assigned the number two slot to his single-movement Short Symphony (1933). The Third Symphony, scored for a large orchestra comprising a total of twenty-six wind and brass players, five percussionists, celesta, piano, two harps, and strings, occupied Copland for over two years. The result proved to be his longest instrumental composition and indeed it is his most clearly symphonic. Despite Copland’s concerns over the pedigree of bona fide symphonies, his Third Symphony contains a few quirks. Although it does not quote any folksongs or hymns, as had many of his previous works, it incorporates his own popular Fanfare for the Common Man (1942) in its entirety, and the Fanfare’s basic melodic contours permeate all four of the symphony’s movements. While Copland was fleshing out the symphony, the United States emerged victorious in the Second World War. It is difficult not to hear the piece as in some way a response to that but Copland has stated that he did not write the symphony as a direct response to the war, although he conceded that its “affirmative tone” was “certainly related to its time.”

Leave a comment