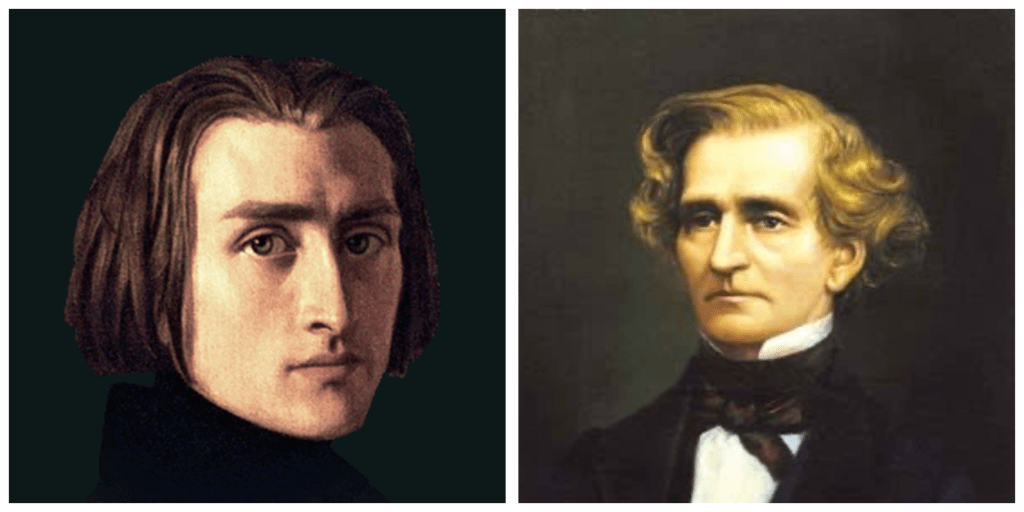

Franz Liszt was the greatest piano virtuoso the world has ever known. He combined extraordinary ability on the keyboard prowess, astonishing creative inspiration with an insatiable love of life. He was a complex genius with great charisma and virtually invented the piano recital as we know it, ensuring that the ordinary man in the street got to hear music that was normally the exclusive preserve of the educated classes. Orchestral concerts were still comparatively rare in the pre-gramophone age, so Liszt set about arranging many symphonic scores for solo piano (most famously Beethoven’s nine symphonies), in addition to composing countless sets of virtuoso fantasias on themes from operas, both popular and obscure. He was also a keen supporter of new music, and did much to establish the rising Nationalist schools in Russia and Bohemia, as well as encouraging the likes of Berlioz, Grieg and, most notably, Wagner.

Grande Fantaisie Symphonique (1834)

Jenő Jandó (piano)

Budapest Symphony Orchestra

András Ligeti (conductor)

Les préludes – Symphonic Poem No.3 (1845-1854)

Philadelphia Orchestra

Riccardo Muti (conductor)

La Campanella (1851)

Lang Lang (piano)

Hungarian Dance No 2 (1851)

Philadelphia Orchestra

Eugene Ormandy (conductor)

In 1832 Berlioz composed Lélio (The Return of Life) as a sequel to the Symphonie fantastique. Even though the work was composed for actor, voices and orchestra, Franz Liszt, thought it worthwhile rearranging for his own instrument in order to bring it to a greater public Liszt, who was amongst Berlioz’s staunchest admirers, had already transcribed the Symphonie for solo piano, but there was no chance of his doing the same for its sequel. Instead, and much to Berlioz’s liking, he used just two themes from Lélio to construct a large-scale work in two parts: the Grande Fantaisie Symphonique. The orchestral writing is full, noble and of symphonic proportions, and the piano part, although a proper solo part, is also fully integrated into the orchestral texture. The original manuscript of this work, long undiscovered, recently surfaced at auction in France (although sadly not in its entirety). Liszt would have no problem playing the piano part in this work as, by the age of 12 he could play virtually anything at sight. He had won the enthusiastic approval of Beethoven when the young boy played his Archduke Piano Trio from memory, with the missing violin and cello parts incorporated as he went along as well as learning Beethoven’s C minor Piano Concerto from memory at a day’s notice. For good measure he was able to sight-read the score of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto with a cigar held between the first and second fingers of his right hand

In the late 1840s, Liszt settled in Weimar and gave up the itinerant life of the international concert star to devote himself to composition and conducting.The third of his twelve symphonic poems , Les Préludes, was begun in 1844 as an overture for a planned choral cantata based on poetry of Joseph Autran, but having abandoned that work, he recast the overture as an independent symphonic poem and associated it, after having completed most of the piece, with Alphonse Lamartine’s poem Les préludes. The work remained uncompleted until 1849 when he drafted a purely symphonic version. Again he laid it aside until 1854, when it was performed by the court orchestra at Weimar. Liszt led the first performance at Weimar, Germany, on February 23, 1854. From the very beginning, Les Préludes established itself as the most popular of Liszt’s symphonic poems.

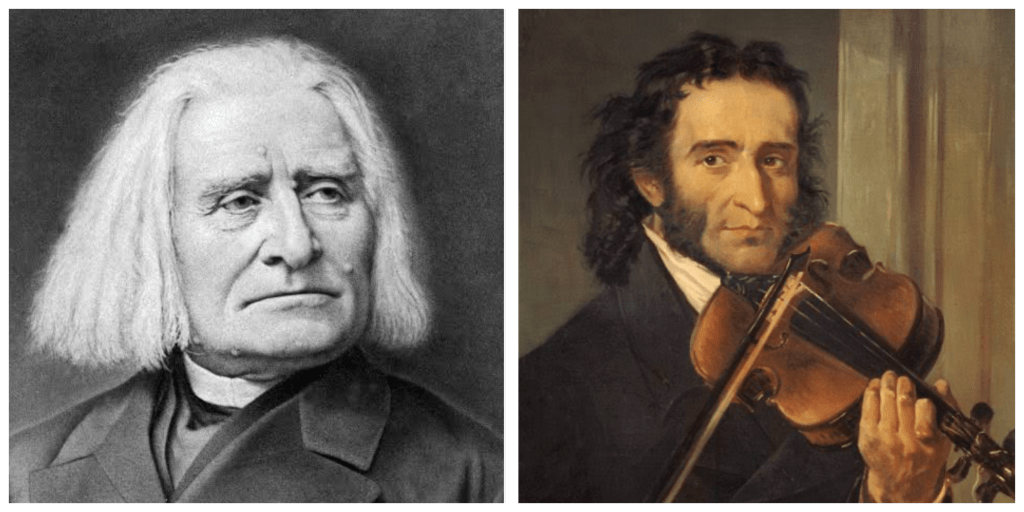

La Campanella (The Little Bell) is the subtitle given to the third of Franz Liszt’s six Grandes études de Paganini, S. 141 (1851). It is a revision of an earlier version from 1838 and is widely considered one of the most technically challenging piano pieces ever written. Its melody comes from the final movement of Niccolò Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in B minor, where the tune was reinforced by a ‘little handbell.’ The étude is played at a brisk allegretto tempo and features constant octave hand jumps between intervals larger than one octave, sometimes even stretching for two whole octaves within the time of a sixteenth note. The work also contains intervals that are 35 half-steps apart (46cm apart on a piano) and also involves other technical difficulties such as trills with the fourth and fifth fingers and fast chromatic passages. Even though Liszt could perform his virtuosic pieces with ease he was more than a mere musical showman. In addition to his colossal achievements as a virtuoso pianist, Liszt also composed in excess of 100 original titles for his instrument. He created the orchestral symphonic poem, and as one of the first great modern conductors no longer content merely to beat time, he employed a vast repertoire of subtle and passionate gestures that transformed the musical shape of the work he was conducting. He devised the leitmotif technique that Wagner used to great effect in his operas, while many of the novel textures we now associate with the Impressionism of Debussy and Ravel were in fact invented by Liszt.

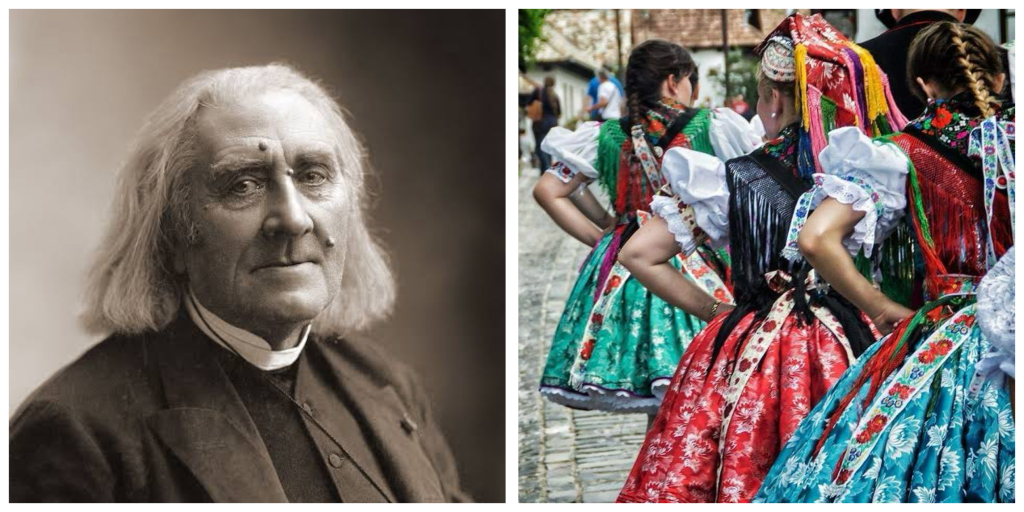

Although Franz Liszt grew up speaking German rather than Hungarian and actually lived relatively little of his life in his native land, he always remained intensely proud of his Hungarian heritage. Among the many colorful stories about him are the accounts of his playing in public while dressed in native folk costume. Amidst the rise of Hungarian nationalism, leading to the Hungarian revolution of 1848 Liszt took on the role of Hungary’s most prominent citizen. Liszt fell easily into his role as symbol of Hungarian independence. Liszt had a strong interest in Hungarian folk music and absorbed its influences in some of his own music. The best known of his folk inspired works are the 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies. Liszt incorporated the Roma style into his music after visiting an encampment and listening carefully to the best Romany musicians. It is a distinctive style with its wildly passionate and exotic in character (heightened by use of the so-called Romany scale which contains 2 striking intervals known to music theory students as augmented 2nds). The Hungarian Rhapsody No.2 in C minor is the best known of the set, and like many of the others, has been arranged for orchestra. To achieve its folk flavour, the Rhapsody is set in the form of a czárdás, a Hungarian dance that is traditionally laid out in two sections, one slow and one fast. In 1861 Liszt moved to Rome, and four years later Pope Pius IX conferred on him the title of ‘Abbé’. Liszt’s later years were dominated by a series of inspired sacred compositions and his piano music became more introspective and meditative. Active to the end, even in 1886 (the year of his death) Liszt embarked on a tour that included his first visit to London in 40 years. He attended performances of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and Parsifal at Bayreuth less than a week before he died from complications from pneumonia.

Leave a comment