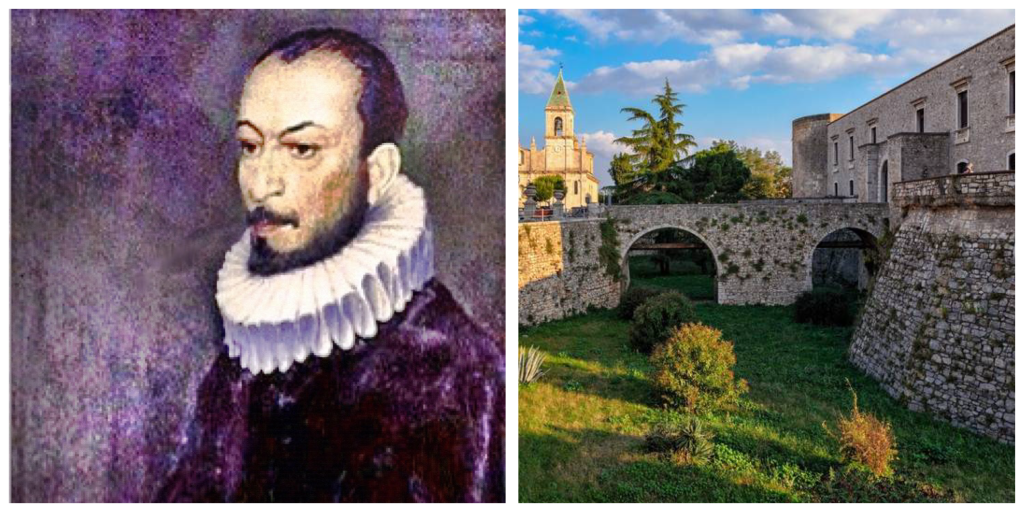

Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa and Count of Conza was an Italian nobleman and lutist of the late Renaissance. He was also a murderer, wife-beater, adulterer, sado-masochist, flagellant, occultist and sublime composer. He was famous for his intensely expressive madrigals, using a chromatic language not heard of until the nineteenth century. His aristocratic family was well connected. His uncle, Carlo Borromeo, was later known as Saint Charles Borromeo and his mother, Girolama, was the niece of Pope Pius IV.

Madrigal: Volan quasi farfalle (1611)

Collegium Vocale Gent

Philip Herreweghe (conductor)

Madrigal: Itene, o miei sospiri

Exaudi Vocal Ensemble

O vos omnes

Cambridge Singers

John Rutter (conductor)

Tenebrae Responsories For Holy Saturday: In tertia nocturno: Responsorium VII: Astiterunt reges terrae

Tenebrae

Nigel Short (conductor)

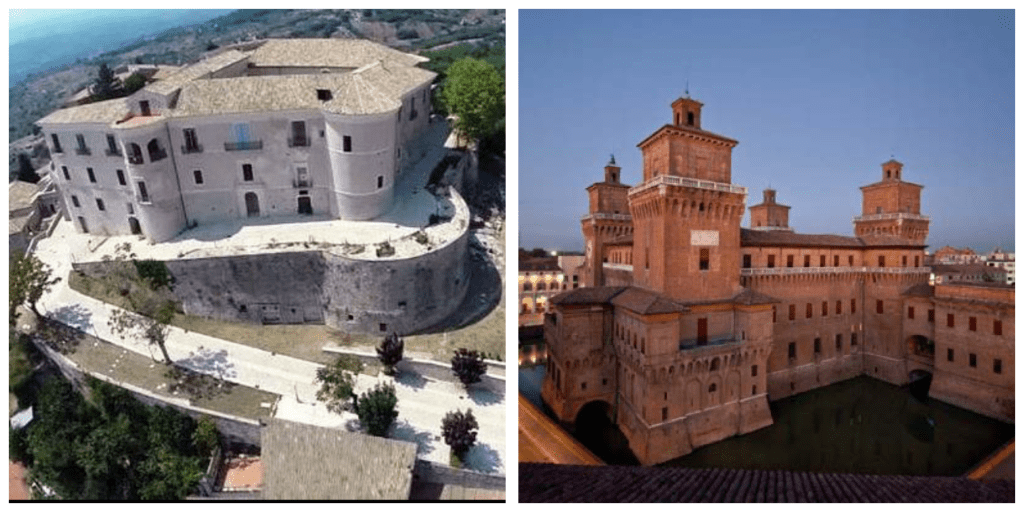

The Gesualdo family, of Norman descent, became lords of the town in the early twelfth century, and a series of advantageous marriages added wealth and power to the line. Gesualdo was slated for the clergy until his late teens, when the death of his older brother destined him for public life. On the night of October 16, 1590, Gesualdo committed a double murder so extravagantly vicious that people are still sifting through the evidence, more than four centuries later. The body of Don Fabrizio Carafa, the Duke of Andria, who was wearing a woman’s nightdress was covered in blood having been both stabbed and shot. Lying on the bed was the body of Donna Maria d’Avalos, Gesualdo’s wife. Her throat had been cut and her nightshirt was drenched in blood. Gesualdo, who was twenty four years old at the time had been seen entering the apartment and reëmerging sometime later with his hands dripping with blood. Ironically wiithin three years, he had married again, to Eleonora d’Este, a cousin of Alfonso II d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara but the second marriage was little happier than the first. Gesualdo reportedly engaged in abusive behaviour and found sexual satisfaction elsewhere. However, what mattered most to him was that his new marriage gave him access to the glittering Ferrara court, and, above all, to its élite circle of musicians.

The madrigals of Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa are considered the pinnacle of a genre which, until the emergence of instrumental genres like the sonata, was the main form of chamber music, frequently performed at aristocratic courts and for the higher echelons of society. It seems likely that the two last books are compilations of madrigals Gesualdo composed over a period of ten years or more. This makes it impossible to connect these ‘late’ madrigals to the composer’s state of mind. The choice of subject is certainly not unusual – love is the main subject of madrigals from the 16th and early 17th century, and, indeed, of secular music throughout history as poems about the trials and tribulations of love offered more opportunities for text expression. There can be little doubt that Gesualdo was his own man in the way he used chromaticism and dissonances and also in his choice of texts. His social standing – being an aristocrat, and therefore completely independent, and not the servant of an employer – gave him total freedom to put his own ideas into practice. In 1613 his complete madrigals were reprinted in score form, which was highly unusual at a time that vocal music was printed in separate parts.

Music was a consuming obsession for Gesualdo and he would speak of nothing else, driving listeners to distraction and showing his works to everybody. He was a man whose underlying personality disorder is exacerbated by various physical and mental traumas at different points in his life into a final state of severe and constant mental torture. The madrigals of the Fifth and Sixth Books are often described as ‘late’ works, having been published at the end of Gesualdo’s life in 1611. Yet by Gesualdo’s own assertion they were composed around the time of his extended sojourn at the court of Ferrara between 1594 and 1597, withheld from publication and only finally published in order to set the record straight and confound his several imitators and plagiarists. Ferrara was the undisputed capital of chromaticism: Vicentino’s microtonal harpsichord, the archicembalo, could still be heard here in the 1590s, played by Luzzasco Luzzaschi, the madrigalist and maestro of the fabled Concerto delle donne. Gesualdo was highly struck by Luzzaschi’s music, and it would seem, from the textual congruences between his Fifth and Sixth books and Luzzaschi’s published collections of the mid 1590s, that the two composers became engaged in some sort of madrigal-publishing duel, or at least mutual artistic exchange. Gesualdo has taken this chromaticism to a place that is personal and profoundly subjective; in these works he seems to be speaking to himself, composing in order to converse with and alleviate his own melancholy rather than to portray or palliate it for others.

Gesualdo wrote music in outrageous defiance of logic and convention, but he was not the only composer in southern Italy who favoured a musical shock tactic; he lived in partial estrangement from society after 1590 (the year of his crimes), but that didn’t stop him from courting the musical world with enthusiasm; and while he was certainly a premier-grade sado-masochist with any number of fascinating perversions, he was actually considered ‘conservative’ in his day, by some standards at least.At the start of the 17th century, Italian music was leading the world away from the edifices of Renaissance polyphony. A new era of melody and accompaniment was dawning, in which the dramatic burden was placed on individual singers to convey emotion through the varied powers of the human voice, rather than through interactions between different musical lines. By contrast, Gesualdo continued to employ the old tools—five or six voices in counterpoint, modal harmony (stretched to the limit, admittedly), no accompaniment—to place his eccentric autograph on the style most closely associated with the house of Este in Ferrara. Where others seasoned their music with the element of surprise, Gesualdo seems intent on distorting every musical line with huge intervallic leaps, shattering every pianissimo with a furious cascade of semi-quavers and spoiling every logical harmonic progression with some piece of chromatic invention. The surprise comes in the perfect cadences and the moments of stillness, and by offering us these occasional moments of musical reprieve, Gesualdo is able to create a pathos no other composer of his era could match. O vos omnes is a responsory, originally sung as part of Roman Catholic liturgies for Holy Week, and now often sung as a motet. The text is adapted from the Latin Vulgate translation of Lamentations 1:12. It was often set, especially in the sixteenth century, as part of the Tenebrae Responsories for Holy Saturday. Gesualdo composed O vos omnes in 1603 for five voices and in 1611 for six voices.O vos omnes was originally sung during Holy Week as part of Roman Catholic liturgies. It is now often sung as a motet.

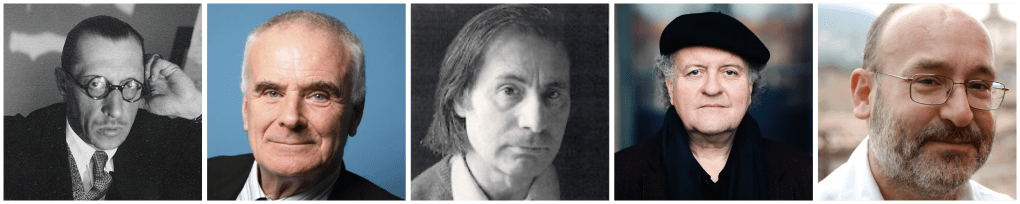

Responsoria et alia ad Officium Hebdomadae Sanctae spectantia is a collection of music for Holy Week by Italian composer Carlo Gesualdo, published in 1611. It consists of three sets of nine short pieces, one set for each of Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday, and a psalm and a hymn. The texts of the Responsories for Holy Week are related to Jesus’s Passion and are sung in between the lessons at Tenebrae. As in Gesualdo’s later books of madrigals, he uses particularly sharp dissonance and shocking chromatic juxtapositions, especially in the parts highlighting text passages having to do with Christ’s suffering, or the guilt of St. Peter in having betrayed Jesus. Gesualdo’s legacy was secured when Igor Stravinsky became Gesualdo’s biggest fan. In 1960, Stravinsky wrote a piece called Monumentum pro Gesualdo, and, eight years later, contributed a preface to Glenn Watkins’s scholarly study Gesualdo: The Man and His Music. The fascination has not abated in recent decades. There have been no fewer than eleven operatic works on the subject of Gesualdo’s life, not to mention a 1995 pseudo-documentary, by Werner Herzog, called Death for Five Voices. No novelist would have dared to invent a savage Renaissance prince who doubled as an avant-garde musical genius, although Gesualdo has appeared in fiction with some regularity..The list of other composers influenced by Gesualdo’s music includes Peter Warlock, Peter Maxwell Davies, Alfred Schnittke, Wolfgang Rihm, and Salvatore Sciarrino. Stravinsky, became enamoured with Gesualdo in the early nineteen-fifties and the sacred pieces of his last years – Canticum Sacrum, Threni, and Requiem Canticles – all contain echoes of Gesualdo.

Leave a comment