Igor Stravinsky was born in 1882 near St. Petersburg, Russia and died in 1971, in New York. He is one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century and a pivotal figure in modernist music. His compositions had a revolutionary impact on musical thought just before and after World War I, and he remained a cornerstone of modernism for much of his long working life.

Scherzo Fantastique (1908)

Montreal Symphony Orchestra

Charles Dutoit

Fireworks (1908)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Pierre Boulez (conductor)

The Firebird: Infernal Dance (1910)

London Symphony Orchestra

Leopold Stokowski (conductor)

Petroushka (1911)

Cleveland Orchestra

Pierre Boulez (conductor)

The Rite of Spring (1913)

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Herbert von Karajan (conductor)

Stravinsky’s music reflected three overarching periods: Russian, Neoclassic, and Serial. Even so, Stravinsky possessed such a powerful musical persona that his music is recognisable regardless of what style he used. In the same way that a Picasso is a Picasso whatever art he was creating, the composer of great ballets such as Firebird and The Rite of Spring are instantly recognisable as the work of Stravinsky. Both these giants of the 20th century worked together, exchanged art, and became fast friends. Stravinsky wrote his Scherzo fantastique, Op 3, between June 1907 and March 1908, at a time when he was still studying with Rimsky-Korsakov. He dedicated it to Alexander Siloti, who conducted the first performance in 1909, after Rimsky-Korsakov’s death. The work is lavishly scored and drew inspiration from Maeterlinck’s The Life of Bee, leading to copyright problems when it was later staged at the Paris Opéra in 1917 as a ballet, with a programme that made specific reference to Maeterlinck. Stravinsky himself later claimed that he had intended the piece as pure symphonic music, without a programme, but when the score was published it included a note on the narrative implicit in the work. The piece starts with music suggesting the life of bees in the hive, leading to a central section introduced by the alto flute and showing the sunrise, the flight of the queen bee, and her contest with her mate, a drone, who dies. The third section, which echoes the first, has the bees busy once more in their daily activities. The Scherzo fantastique is a brilliant orchestral showpiece, scored with a skill of which Rimsky-Korsakov expressed his approval. In February 1909 the Scherzo fantastique was performed in St. Petersburg at a concert attended by the impresario Serge Diaghilev, who was so impressed by Stravinsky’s promise as a composer that he quickly commissioned some orchestral arrangements for the summer season of his Ballets Russes in Paris.

Fireworks is one of the first products of his study with Rimsky-Korsakoff and can be heard almost as an homage to his teacher. It occupies an important place in Stravinsky’s output for two reasons. First, it his first fully characteristic piece in which his own voice emerged for the first time, unencumbered by echoes of his forebears. Second, Fireworks received the attention of the influential impresario Serge Diaghilev. Stravinsky wrote Fireworks as a wedding present for Nadezhda Rimsky-Korsakov, daughter of composer and pedagogue Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Stravinsky’s most important teacher, and another Rimsky pupil, Maximilian Steinberg. The audience at the work’s first public performance wasn’t particularly warm towards the piece, but more importantly, the work made an impression on Diaghilev. Fireworks gave Diaghilev the encouragement he needed to commission a full-length ballet from Stravinsky – the result was The Firebird, a score foreshadowed by Fireworks in many ways. By the time of Fireworks’ public premiere, Diaghilev was already laying the groundwork for Stravinsky’s success – a review written by the impresario himself praised Fireworks as music distinguished by its “richness of substance.” Stravinsky’s Fireworks, with its quirky harmonic twists and transparent orchestration points the way forward to The Firebird and the later Diaghilev ballets.

In 1909, the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev was running out of time. After a key backer of his ventures dropped dead, Diaghilev had been forced to abandon his plans to present Russian opera in Paris in the spring of 1910. Instead, he would present the more cost-effective art form of ballet. In recent years, Paris had been swept by a vogue for all things Russian, and Diaghilev was quick to capitalise on the trend with performances of Russian operas, ballets and concert music. He wanted to create integrated works of art that encapsulated music, theatre and visual design, fresh and vibrant, yet rooted in the soil of primaeval Russia. Diaghilev chose a character from Russian folklore symbolising rebirth, beauty, and magic – The Firebird – so he set about creating about a new ballet that would realise his ideals and show the world that Russian art was at the cutting edge of sophistication. Diaghilev originally planned to hire a composer with whom he had worked before, Alexander Tcherepnin, but he dropped out. Next Diaghilev turned to Anatoly Lyadov, but he also fell through, possibly because the project came at such short notice. Diaghilev briefly considered Alexander Glazunov, then Russia’s leading composer, but he wasn’t interested. Running out of options, he turned to a young, relatively untested composer who had orchestrated two pieces by Chopin for a Diaghilev ballet the year before: Igor Stravinsky. Stravinsky got to work even before Diaghilev had made him a formal offer. Eager to make the ballet as Russian as possible, Diaghilev’s team concocted a story that combined the most famous characters from half-a-dozen Russian fairy tales, including the Firebird, Prince Ivan-Tsarevich, thirteen dancing princesses and the evil sorcerer-king Kashchey the Deathless. The premiere on June 25, 1910 caused a sensation and catapulted Stravinsky to international fame.

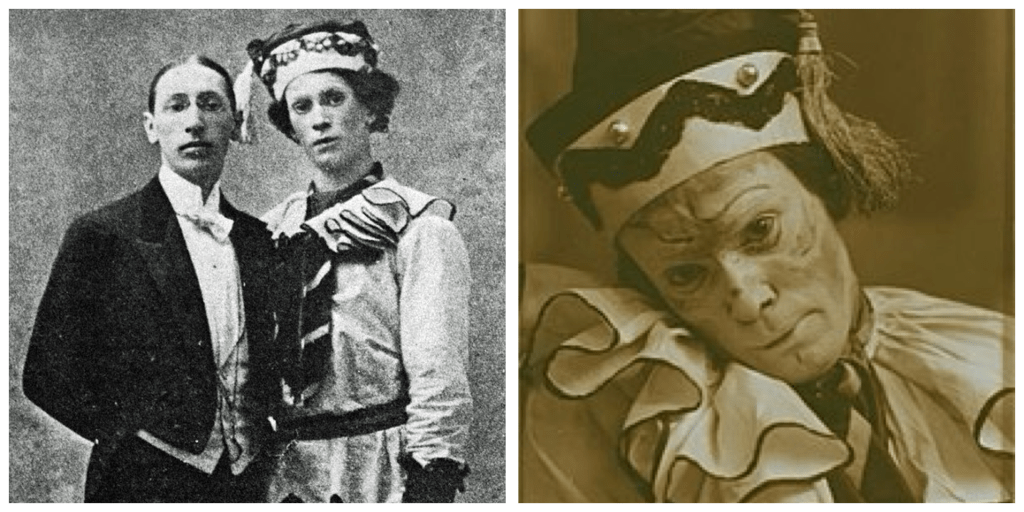

With the premiere of The Firebird in 1910, Igor Stravinsky became an instant household name. After The Firebird’s stunning success, Serge Diaghilev, the impresario of the Ballets Russes, lost no time in commissioning a second ballet from Stravinsky. The young composer was writing a piano concerto at the time, but when Diaghilev heard it, he immediately realised its potential as a theatrical piece, and encouraged Stravinsky to rework it into a ballet. The character of Petroushka (also known as Punch, Pulcinella or Polichinelle) dates from the 16th-century Italian Commedia dell’arte. In Stravinsky’s version, Petroushka is a figure of pity, the eternal outsider whose vain attempts to gain acceptance arouse both compassion and contempt. The primitive edginess of Stravinsky’s music in Petroushka captures the nature of the story and its characters, who represent human emotions in their most raw form: Petrushka, the despised pariah yearning for love; the Ballerina, an unattainable emblem of beauty and desirability; and the ill-mannered Moor, who epitomises all the base, loutish aspects of the human psyche. Petroushka premiered on June 13, 1911, at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. Pierre Monteux conducted, and Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes danced to choreography by Michel Fokine, set and costume design by Alexandre Benois, and Vaclav Nijinsky dancing the title role.

In 1910, Stravinsky was the toast of Paris. Little did the Parisian world know that simultaneously he was hatching a plan to write a fantasy piece in various episodes describing a violent, ruthless pagan ritual. In The Rite of Spring he presented a new concept of music involving constantly changing rhythms and metric imbalances, a brilliantly original orchestration, and drastically dissonant harmonies that have resonated throughout the 20th century. In 1911, while in Clarens, Switzerland, he felt ready to jot down the first notes of his Rite. One year earlier, in 1910, he had enlisted the help of archeologist and folklorist Nikolai Roerich (an ex pat living in Paris) to ensure authenticity. As the piece developed, he worked closely with Roerich, and during 1912-1913 The Rite of Spring was referred to as ‘our child’. The composer was so indebted that he dedicated the score to Roerich. For a while, he viewed his ‘fantasy’ as a possible symphony, but was persuaded by Serge Diaghilev to turn it into a ballet. On May 28, 1913, he changed a few ideas, and the following day, The Rite of Spring was produced at the Theatre des Champs Elysees to an astonished audience. In place of the elegance of classical ballet, the dancers gyrated their pelvises; arms and legs were sharply bent. When the curtain rose on a group of knock-kneed, pigeon-toed, long-braided yet seductive young women jumping up and down in hideous costumes, the audience went berserk. But the visual shock was nothing compared to the music. Upon hearing the brash, frightening score, the first-time audience dissolved into angry shouts, catcalls, whistles, and fistfights in the aisles degenerated into a riot. Diaghilev raced backstage to turn the lights on and off to calm the attendees but to no avail. On the side, the choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky mounted a chair and screamed step numbers to the dancers who were unable to hear the music. Camille Saint-Säens ran from the theatre in a fury. The conductor, Pierre Monteux, who had thought Stravinsky was ‘raving mad’, stood his ground on the podium apparently impervious to the commotion. Monteux anticipated that the music might cause a scandal — he was wrong. It was a revolution. Police were called, and Stravinsky was infuriated. The audience were infuriated by the overt sexuality of the subject and depiction of a primordial world, harmonic dissonance, frenzied rhythmic changes and unpredictable offbeat accents, savage ostinati (repeated patterns) wild dynamics, and distorted, quirky melodies that they felt were incoherent. Pierre Boulez has noted, ‘The Rite of Spring serves as a point of reference to all who seek to establish the birth certificate of what is called contemporary music’ whilst Aaron Copland, in his 1951 Norton Lecture series at Harvard, considered The Rite of Spring to be “the foremost orchestral achievement of the twentieth century.”

Leave a comment