Herbert von Karajan was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 34 years. He was closely associated with the Salzburg Festival and the Vienna Philharmonic and is generally regarded as one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century, He was a controversial but dominant figure in European classical music from the mid-1950s until his death. A key part of his legacy is the large number of recordings he made and their prominence during his lifetime, selling an estimated 200 million records.

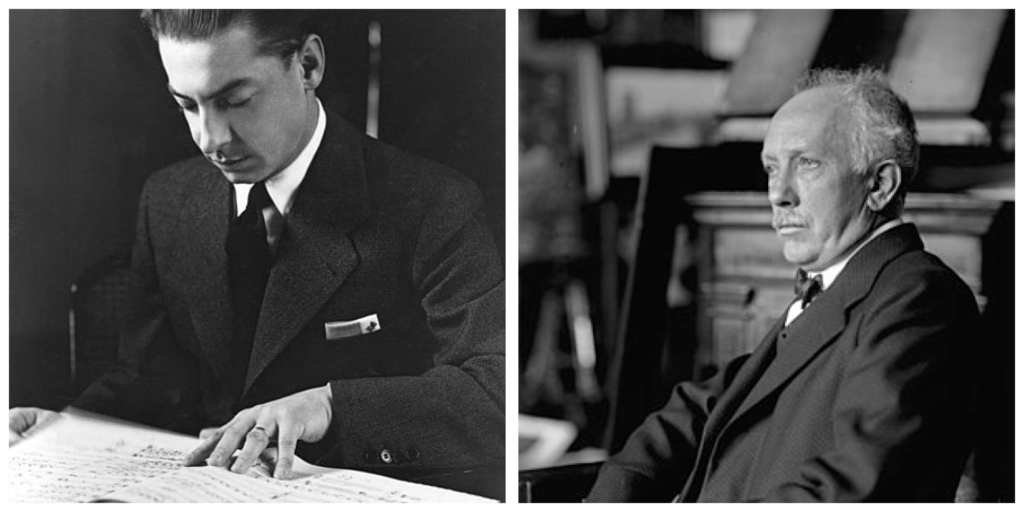

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Der Rosenkavalier: Introduction to Act I (1956)

Philharmonia Chorus and Orch / Karajan

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No 5 Movt IV: Finale (1984)

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Karajan

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg Act III Scene 5 (1951)

Bayreuth Festival Chorus and Orchestra / Karajan

Pietro Mascagni (1863-1945)

Intermezzo from Cavalleri Rusticana (1967)

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra/ Karajan

(Last recording 1995)

Anton Bruckner Symphony No. 7 (1824-1896)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Karajan

Herbert von Karajan was born on 5th April 1908 in Salzburg, the son of a successful physician. As a youth he studied music and conducting in Salzburg and in 1929 he took up the position of orchestra conductor in Ulm. In 1934 was appointed as Kapellmeister at Aachen, where he remained until 1941 and he made a name for himself in Berlin as a conductor of contemporary music, particularly the works of Carl Orff and Richard Strauss. Von Karajan led the Vienna Philharmonic for the first time in Salzburg in 1934, and from 1934 to 1941 he was engaged to conduct operatic and symphony orchestra concerts at the Theatre Aachen. He made his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1937 and in 1938 he conducted the Berlin State Opera in a production of Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde which was a spectacular success. Soon after, he signed a lucrative contract with Deutsche Grammophon. Receiving a contract with the Deutsche Grammophon record label that same year, von Karajan made the first of hundreds of recordings, conducting the Staatskapelle Berlin in the overture to The Magic Flute. Constantly striving to further his career, von Karajan was irked by the looming figure of Wilhelm Furtwängler – a man who, despite his politically ambiguous relationship to the Reich, was the undisputed pre-eminent German conductor.

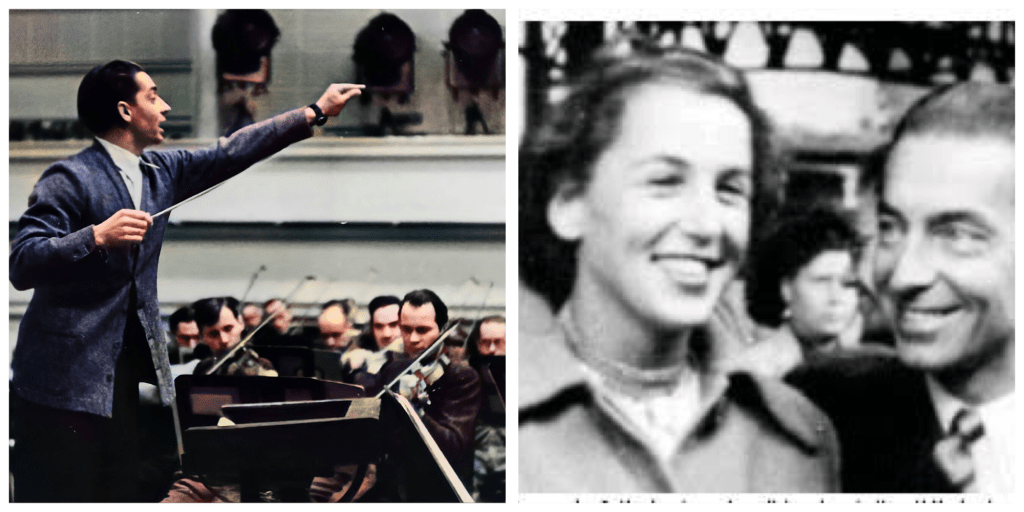

It was also in 1933 that von Karajan became a member of the Nazi party and one of the leading musicians of the Third Reich, for which he would later be criticised. Like many of his fellow non-Jewish German musicians, however, von Karajan was to emerge from World War II relatively unscathed, going on to become one of the most-recorded musicians in the world. While his egotism and ambition were no secret, his political convictions were vague enough to allow the post-war musical world to look the other way. Although von Karajan never involved himself in any explicit political affairs, he profited from the re-organisation of the musical world under Hitler. Eventually his name was included in Goebbels’ list of musicians ‘blessed by God’. In 1939 von Karajan led a performance of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger that was a total failure. Hitler, in the audience, took this as a personal affront and purportedly never forgave him. Even more scandalously, von Karajan married Anita Gutermann, the heiress to a textile fortune whose grandfather was Jewish. By 1944, von Karajan was, in his own words, losing favor with the Nazi leadership, but he still conducted concerts in wartime Berlin. In the closing stages of the war, he and his wife Anita fled Germany for Milan. He was discharged by the Austrian denazification examining board on 18 March 1946 and resumed his conducting career shortly afterwards

After the war, the Soviets issued a prohibition on the conductor’s public performances – his voluntary entrance into the Nazi party several years before the war began was enough to condemn him. In 1946, von Karajan gave his first post-war concert in Vienna with the Vienna Philharmonic, but he was banned from further conducting by the Soviet occupation because of his previous Nazi party membership. By 1947, though, all bans had been lifted, and he was free to perform and conduct at will. On 28 October 1947, he gave his first public concert following the lifting of the ban. With the Vienna Philharmonic, he recorded Johannes Brahms’ A German Requiem. The clearing of his name was largely thanks to his part-Jewish wife, whose Jewishness he exploited in order to plead ‘resistance’ to the Reich. Some historians believe that he deliberately lied in order to ensure his denazification. In any case, his career continued on its astronomical trajectory toward fame and fortune. In 1949, von Karajan became artistic director of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Vienna. He also conducted at La Scala in Milan. His most prominent activity at this time was recording with the newly formed Philharmonia Orchestra in London, helping to build them into one of the world’s finest. Starting from this year, von Karajan began his lifelong attendance at the Lucerne Festival.

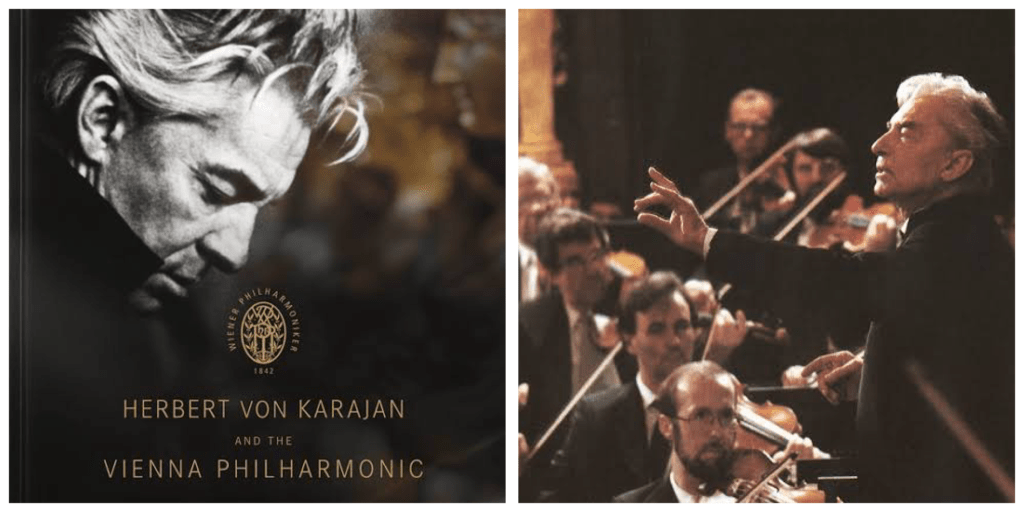

In 1955 he was appointed music director for life of the Berlin Philharmonic as successor to Furtwängler. From 1957 to 1964 he was artistic director of the Vienna State Opera and became closely involved with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Salzburg Festival, where he initiated the Easter Festival. With the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra von Karajan became known for his podium presence, the fluidity of his gestures, the passionate intensity of his music-making, his meticulous preparation in rehearsal and pursuit of perfection in performance. He also embraced recording technology from the introduction of the LP and stereo sound to the arrival of digital recording. In 1959 he signed a new exclusive agreement with Deutsche Grammophon and, over the next three decades, made some 330 records for the yellow label. His partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic, fully documented by DG, delivered recordings of everything from Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos to Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra Op.31. Released in 1963, the first complete set of Beethoven’s symphonies, bringing together Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic, remains the greatest landmark in the label’s history. In 1980, Herbert von Karajan conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in DG’s first digital recording; they continued to set trends two years later when they recorded Strauss’s Eine Alpensinfonie for the yellow label’s first mass-produced CD. Deutsche Grammophon released Karajan’s debut recording, the overture to Die Zauberflöte with the Berlin Staatskapelle in 1939 and he made his final album for the yellow label, Bruckner’s Symphony No.7 with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, fifty years later.

Von Karajan continued to perform, conduct and record prolifically, mainly with the Berlin Philharmonic and the Vienna Philharmonic. He was the recipient of multiple honours and awards. He became a Grand Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic on 17 May 1960 and in 1961, he received the Austrian Medal for Science and Art. He also received the Grand Merit Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. He remained the artistic director of the Berlin Philharmonic until he retired in 1989, due to poor health. Soon after retiring, von Karajan died in Salzburg, one of the wealthiest and most famous conductors in the world. In his latter years, Karajan suffered from heart problems as well as undergoing surgery on his back. He increasingly came into conflict with the Berlin Philharmonic for his old-fashioned dictatorial style of leadership. He died of a heart attack on 16 July 1989 at the age of 81.

Leave a comment