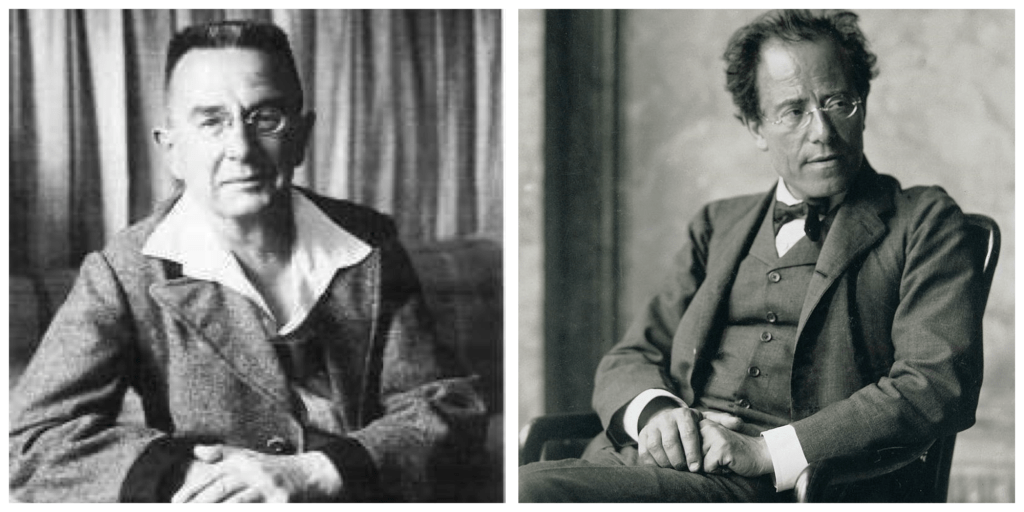

Franz Schmidt (1874–1939) was an Austrian-Hungarian composer, pianist, organist, and cellist, born in Pressburg (now Bratislava) and later based in Vienna. His music is rooted in the late-Romantic tradition, drawing inspiration from Brahms, Bruckner, Mahler, and Wagner, and is known for its lush orchestration, Hungarian-tinged melodies, and contrapuntal mastery. Despite his melodic gifts—often considered superior to those of contemporaries like Schoenberg and Reger—Schmidt faced stiff competition from both late-Romantic giants and the emerging modernist and nationalist composers of the early 20th century, such as Stravinsky, Bartók, and Schoenberg.

Schmidt showed remarkable musical talent from an early age. After moving to Vienna in 1888, he studied piano with Theodor Leschetizky, composition with Robert Fuchs, cello with Ferdinand Hellmesberger, and counterpoint with Anton Bruckner. He became a skilled pianist, cellist, and amateur trumpet player, and played cello solos under Gustav Mahler in the Vienna Philharmonic. In 1914, he became a professor of piano at the Vienna Conservatory, later serving as its director and rector between 1925 and 1937.

His compositional output includes four symphonies, the operas Notre Dame and Fredigundis, the oratorio The Book with Seven Seals, concerti, orchestral works, chamber music, and organ pieces. Schmidt’s style remained firmly tonal and melodic, contrasting with the avant-garde trends of his era. Critics sometimes dismissed his work as conservative, but his symphonies are now recognized for their bold optimism and emotional depth.

Franz Schmidt

Symphony No 3

IV. Allegro moderato

BBC National Orchestra of Wales

Jonathan Berman (conductor)

Franz Schmidt

Symphony No 1 III. Schnell und Liecht

Frankfurt Radio Symphony

Paavo Järvi (conductor)

Franz Schmidt

Music for Orchestra in One Movement

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Kirill Petrenko (conductor)

Franz Schmidt

Symphony No 4 in C Major

III. Molto vivace

Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Neeme Järvi

Franz Schmidt

Symphony No 2 III. Finale Langsam

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Neeme Järvi (conductor)

Franz Schmidt

Symphony No 3

Franz Schmidt composed his Symphony No. 3 in A major between 1927 and 1928 for the Columbia Gramophone Company’s international competition, which marked the centenary of Schubert’s death. The work premiered in 1928 with the Vienna Philharmonic. While it was highly praised in Austria and won the national section of the competition, it ultimately finished second overall to Kurt Atterberg’s Sixth Symphony, which claimed the top prize. Schmidt’s Third Symphony pays homage to Schubert but also draws on the styles of Brahms, Bruckner, and Richard Strauss. The music blends late-Romantic tradition with some harmonic ideas that were considered innovative at the time, resulting in a symphony that is both rooted in the past and forward-looking.

The symphony’s structure is traditional, comprising four movements. The third movement is featured in this week’s programme and is a lively, dance-like Scherzo, with the finale shifting from a solemn chorale to an exuberant, tarantella-inspired dance. Scored for a standard orchestra – pairs of woodwinds, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, strings, and timpani—the symphony offers a an insight into Schmidt’s skillful orchestration.

Critical opinions are still mixed one hundred years after its composition. Some consider the symphony charming and tuneful but lacking dramatic tension, while others find it a rewarding and substantial work. Although it remains relatively obscure outside Austria, Schmidt’s Symphony No. 3 stands as a significant example of early 20th-century orchestral music and offers a rich blend of melody and harmonic complexity for those who explore it.

Franz Schmidt (1874–1939)

Symphony No 1 (Composed between 1896 and 1899)

Franz Schmidt’s Symphony No. 1 in E major stands as a remarkable achievement from a young composer, written between 1896 and 1899 when Schmidt was just 22 years old. Premiered in Vienna in 1902 and dedicated to Archduchess Isabella, the symphony quickly found favour with conservative Viennese audiences, even enjoying greater initial success than Mahler’s early works, thanks to its lush late-Romantic style and adherence to tradition.

This four-movement symphony opens with a slow introduction that transitions into a lively, Wagnerian first movement, reminiscent of Die Meistersinger, showing us, at an early age, Schmidt’s command of orchestral writing. The second movement is again enveloped in Wagnerian harmonies and ambiguous tonality. The scherzo, marked Schnell und leicht, emerges as the symphony’s highlight, brimming with a captivating melody, unexpected harmonic turns, and vibrant woodwind writing – offering a glimpse of the mature Schmidt to come. The finale is lively but never rushed, culminating in a chorale that affirms Schmidt’s contrapuntal skill and mastery of orchestral colour.

Scored for a large orchestra – including piccolo, flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets, trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings – the symphony draws clear influences from Wagner, Bruckner, and Richard Strauss and is orchestrated to give the listener a rich and lyrical sound world. Though regarded as Schmidt’s most conventional symphony, it hints at the individuality that would define his later works. Since their composition, Schmidt’s symphonies have been underrated compared to those of Zemlinsky or Korngold, but recent recordings—such as those by Vassily Sinaisky with the Malmö Symphony Orchestra, Jonathan Berman with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, and Paavo Järvi with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony – have sparked renewed interest and appreciation. Today, Symphony No. 1 is recognised not only for its technical assurance and orchestral imagination but also as a bridge between the grand Romantic tradition and the evolving Viennese style of the early twentieth century.

Anton Karlinsky (Wien Museum)

Franz Schmidt

Music for Orchestra in One Movement

Composed in 1930 during the transitional period between his Third and Fourth Symphonies, Music for Orchestra in One Movement defies conventional expectations through its single-movement structure which , abandons the traditional four movements in favour of a continuous, eveloving flow. The orchestration has dense “organ-like” sonorities, layered string chorales with intricate woodwind melodic lines with dramatic brass interjections to create a colourful tapestry of sound. Harmonically, it remains rooted in tonality but enriches its palette with modal inflections and chromatic twists, balancing familiarity with subtle tension. Stylistically, the piece bridges two eras: its lyrical themes echo Brahms’ introspective warmth, while the climaxes surge with Brucknerian grandeur.

Schmidt paces his symphony as if borrowing from Wagner’s operatic innovations which gives the overall shape of the work a sense of urgency. Unlike many of his contemporaries who were leaning toward modernism, the work remains anchored in late-Romantic traditions although there are hints of ealry 20th-century experimentation. The piece, similar to many of Schmidt’s other orchestral work, languished in obscurity and was dismissed due to its unconventional form. However, this Berliner Philharmonic Orchestra’s 2020 recording has reignited interest and revealed a subtle mix of momentum and reflection. At least, the symphony can be seen as a bridge between Romanticism and modernity and demands precise tempi and dynamic control to balance its unusual structure. The work stands as a testament to Schmidt’s mastery of orchestral storytelling and his quiet defiance of musical orthodoxy.

Franz Schmidt

Symphony No 4 in C Major

Composed in 1933 as a requiem for his daughter Emma, who tragically died in childbirth, Franz Schmidt’s Fourth Symphony stands as one of the 20th century’s most profound symphonic works. Born from personal grief and the composer’s own reckoning with declining health, it merges raw emotion with masterful craftsmanship. Though overshadowed by avant-garde contemporaries like Schoenberg and Webern, the symphony remains a towering achievement in late-Romantic orchestral writing – its introspective power and structural daring deserving far greater recognition than its underperformed status suggests.

Premiering on January 10, 1934, at Vienna’s Musikverein under Oswald Kabasta, the work defied the era’s modernist currents to critical acclaim. Its four interconnected sections unfold as a continuous 42-minute meditation on loss and acceptance. A solitary trumpet opens the Allegro molto moderato–Passionato, followed by the Adagio in which a cello’s mournful solo spirals into a funeral march.. In stark contrast, the Molto vivace erupts with viola-led dances—a fleeting respite before the music surges into a Mahlerian climax. The finale (Tempo primo) returns to the trumpet’s opening theme, fading slowly into a whisper.

The score avoids melodrama for restraint with its lush orchestration focused on the solo voices of trumpet, cello and viola.. While Schmidt’s later association with Nazi authorities complicates his legacy, the symphony itself transcends his biography, its emotional universality undimmed. Conductors like Zubin Mehta and Kirill Petrenko have championed its cause, while recordings by Martin Sieghart (1996) and Paavo Järvi (2020) capture its grandeur and intimacy alike. The Fourth Symphony can be seen as art’s power to transform sorrow into beauty – with its quiet radiance, structural boldness, and unflinching honesty. Schmidt’s masterpiece is a timeless monument to the human capacity to endure.

Franz Schmidt

Symphony No 2 III. Finale Langsam

Franz Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2, composed between 1911 and 1913 and premiered in Vienna under Franz Schalk, is a technically demanding work for strings, notable for its formal innovation: a prelude, a set of variations with scherzo and coda, all unified by a single melodic idea. The finale contrasts with the earlier brisk movements by adopting a slower tempo, Langsam. Schmidt’s fondness for variation form is evident here, as in his other works, and the symphony is also marked by energetic fanfares and a lush, organ-like orchestration.

Despite his craftsmanship, Schmidt’s international reputation suffered for two main reasons. He was poor at self-promotion, leading to conflicts with figures like Mahler and Arnold Rose. More damagingly, after Austria’s 1938 Anschluss, the Nazis appropriated his music, commissioning the unfinished cantata The German Resurrection. Although Schmidt was politically naïve rather than a Nazi, this association deeply harmed his posthumous reputation, and his works remain largely neglected outside Vienna.

——————————————

Leave a comment