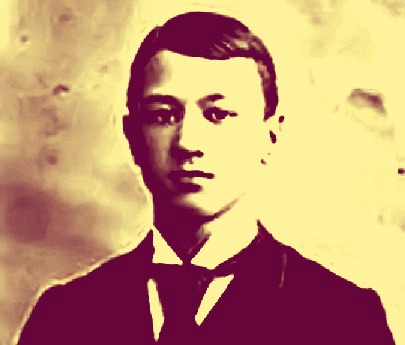

Charles Ives stands as a pioneering figure in American classical music, renowned for his groundbreaking innovations and his integration of American cultural elements into the modernist tradition. Born in Danbury, Connecticut, Ives was the son of George Ives, a bandleader and music teacher who encouraged his son’s early experimentation with sound. Charles became a church organist at just 14 and composed his first works during his teenage years, displaying both musical precocity and a willingness to challenge conventions.

Charles Ives

Symphony No 1 (1898-1902) III. Scherzo Vivace

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Sir Andrew Davis

Charles Ives

Symphony No 2 (1897-1910) II. Allegro

New York Philharmonic Orchestra

Leonard Bernstein (conductor)

Charles Ives

Symphony No 3 (1901-1904) II: Children’s Day

Northern Sinfonia

James Sinclair (conductor)

Charles Ives

Symphony No 4 (1910-1925) III. Andante moderato

American Symphony Orchestra

Leon botstein (conductor)

Charles Ives

Holidays Symphony: Decoration Day (1912)

Malmo Symphony Orchestra

James Sinclair (conductor)

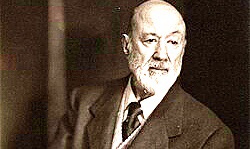

Ives attended Yale University, where he studied composition with Horatio Parker. Although he mastered the European Romantic tradition, Ives was already developing a distinctive voice, blending the forms and harmonies of European music with the hymns, marches, and folk tunes of his American upbringing. After graduating in 1898, he chose a career in insurance to provide financial stability. He became a pioneer in estate planning, publishing the influential Life Insurance with Relation to Inheritance Tax in 1918.

Charles Ives

Symphony No 1 (1898-1902)

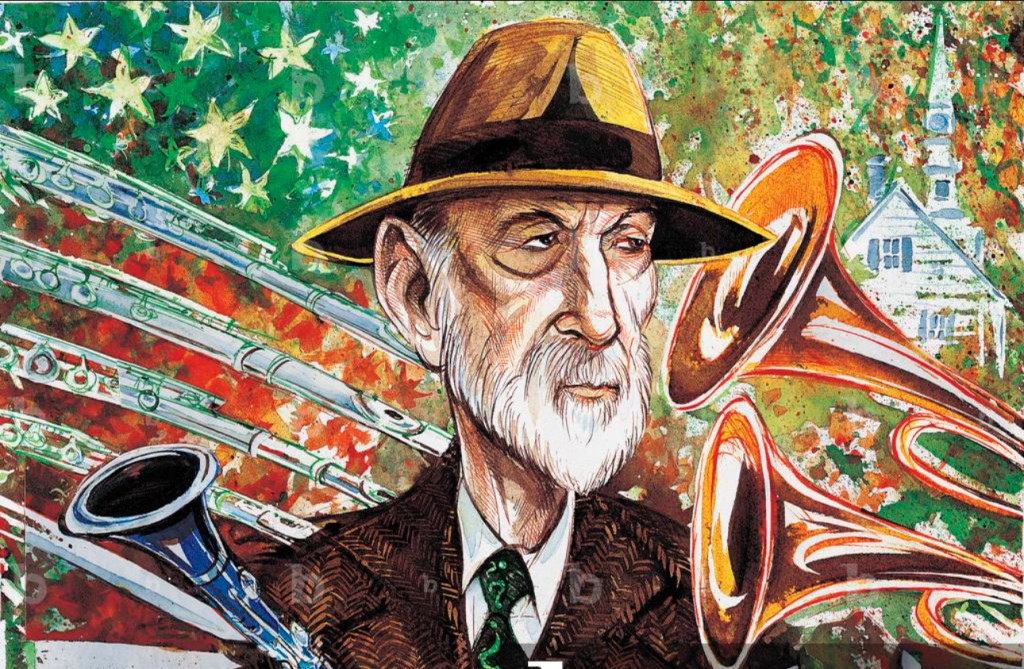

Despite his business commitments, Ives composed prolifically in his spare time, often in the evenings and on weekends. His music is characterised by sharp dissonance, polytonality, polymeter, tone clusters, microtonal intervals, and elements of chance – techniques that placed him far ahead of his contemporaries and anticipated many later developments in 20th-century music. Ives believed that all sound could be music, a philosophy reflected in his experimental approach and his frequent quotation of American popular and church music within complex classical structures.

Charles Ives’ Symphony No. 1 in D minor, begun in 1894 and primarily composed during his years at Yale (1898–1902), stands as a testament to his early mastery of the European Romantic symphonic tradition. The work was revised in 1908 but did not receive its first performance until 1971, when it was conducted by Zubin Mehta. The symphony is orchestrated for a full Romantic-era ensemble, including 2 flutes (with an optional third), English horn, contrabassoon, brass, timpani, and strings and is deeply indebted to European Romantic composers, especially Dvořák, Tchaikovsky, and Schubert. While the symphony is more conventional than Ives’ later works, it already hints at his future experimentalism, with adventurous modulations and subtle touches of bi-tonality.

Although Ives himself later dismissed the symphony as somewhat derivative, modern critics praise its craftsmanship, energy, and emotional range. Today, it is recognized as an important early American symphonic work, bridging 19th-century Romanticism and the emerging voice of 20th-century American modernism. Ultimately, Ives’ Symphony No. 1 reveals a young composer absorbing and mastering the traditions of his predecessors, even as he lays the groundwork for his own innovative contributions to American music.

Ives’s graduation portrait from Yale University, c. June 1898

Charles Ives

Symphony No 2 (1897-1910)

Most of Ives’s major works were composed before 1915, including his four symphonies, orchestral sets such as Three Places in New England, chamber music, and the monumental Piano Sonata No. 2. Many of these works remained unpublished or unperformed until late in his life or after his death. Chronic health issues, including heart problems and diabetes, eventually curtailed both his business and musical activities.

Charles Ives composed his Symphony No. 2 between 1897 and 1902, later revising it from 1907 to 1910. The symphony runs about 40 minutes and is notable for its fusion of American folk tunes, hymns, and European Romantic influences. Ives scored the work for a large orchestra, including piccolo, contrabassoon, and an expanded brass section, writing the symphony while working in the insurance business, balancing his musical ambitions with a practical career. Despite being completed around 1902, the work was not premiered until 1951, when Leonard Bernstein conducted the New York Philharmonic nearly half a century later.

Musically, Ives integrates over a dozen American folk melodies, hymns such as Massa’s in de Cold Ground and marches, while also referencing European composers like Brahms, Dvořák, and Bach. He subverts classical symphonic development by layering chaotic, overlapping musical ideas, evoking the soundscape of a bustling town meeting. The legacy of Symphony No. 2 lies in its bridging of European symphonic tradition with American vernacular music. Its innovative, energetic finale and irreverent style influenced later American composers, including Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein. The work stands as a landmark in American music, marking Ives’ transition from European models toward a distinctly American voice.

Charles Ives

Symphony No 3 (1901-1904)

Many of Ives’ works remained unpublished or unperformed until late in his life or after his death. Chronic health issues, including heart problems and diabetes, eventually curtailed both his business and musical activities. Recognition for Ives’s music came late. In 1947, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his Third Symphony, and his Second Symphony was finally performed in full half a century after its composition. Today, Ives is celebrated as America’s first great composer, an iconoclast whose work embodies the spirit and diversity of American life, and whose legacy influenced generations of composers both in the United States and abroad

The Symphony No. 3, known as The Camp Meeting, was composed primarily between 1901 and 1904, with the final orchestration completed in 1911. The symphony is deeply rooted in Ives’ childhood experiences at evangelical camp meetings in New England, gatherings characterised by spirited hymn singing and intense religious emotion. These formative memories, especially the communal singing led by his father, profoundly influenced the work’s atmosphere and musical material.

Ives employs a chamber orchestra for this symphony, scoring it for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, two horns, trombone, bells, and strings. This smaller ensemble creates an intimate sound world, often reminiscent of a singing congregation rather than a grand symphonic statement. Stylistically, Ives bridges traditional symphonic forms with his own innovative ‘cumulative form,’ where fragments of melody gradually accumulate and only fully emerge at the end of a movement, effectively reversing the logic of classical sonata form. Nearly all the melodic material is derived from Protestant hymns and folk tunes, reflecting both Ives’ personal history and broader American musical traditions.

Despite being composed in the early 20th century, Symphony No. 3 was not premiered until 1946, when Lou Harrison conducted the first performance. The following year, the work was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music, an honour Ives shared with Harrison. The symphony stands as a pivotal work in Ives’ output, marking a transition between classical influences and his pioneering use of American vernacular music, distinguished by emotional depth and historical resonance.

Charles Ives

Symphony No 4 (1910-1925)

Charles Ives’ Symphony No. 4 is a monumental and intricate work, often described as his masterpiece and one of his most definitive achievements as a composer. Written between 1910 and the mid-1920s, the symphony’s creation spanned many years of meticulous refinement, with Ives drawing on techniques and material from his earlier compositions. The second movement, Comedy, was the last to be completed, likely around 1924.

The symphony is renowned for its multilayered complexity, so much so that performances typically require two conductors to manage its intricate rhythms and overlapping textures. Ives employs a massive and varied orchestra, including instruments such as piccolo, flutes, oboes, clarinets, tenor or baritone saxophone, quarter-tone piano, ether organ (now often played on an ondes Martenot), gongs, Indian drum, offstage ensembles, and a chorus. The use of quarter tones, especially in the strings and piano, and the inclusion of offstage and percussion groups, add to the symphony’s unique sound world

The symphony’s aesthetic program is philosophical, exploring the searching questions of ‘What?’ and ‘Why?’. The first movement poses these existential questions, while the subsequent movements present various responses. The finale, in particular, is seen as a culmination or apotheosis, contemplating the reality of existence and spiritual experience.

The first partial performance – just the first two movements – occurred in 1927 at New York’s Town Hall. The complete symphony was not heard until 1965, when Leopold Stokowski conducted its premiere at Carnegie Hall with the American Symphony Orchestra. Ives’ Symphony No. 4 stands as a summation of his compositional innovations, blending hymn tunes, popular melodies, collage-like layering, and advanced rhythmic experimentation. Its complexity, scale, and ambition have ensured its place as a landmark of 20th-century music.

Charles Ives

Holidays Symphony: Decoration Day (1912)

Decoration Day is the evocative second movement of Charles Ives’ orchestral suite, New England Holidays Symphony, composed in 1912 and lasting about nine minutes. The piece serves as a vivid musical recollection of Ives’ childhood experiences of Decoration Day—now known as Memorial Day—in late nineteenth-century Connecticut. Drawing inspiration from the annual ceremonies he witnessed as a boy, Ives channels the sights and sounds of his father’s marching band, which would lead the townspeople from the Soldiers’ Monument to Wooster Cemetery in solemn remembrance of the Civil War dead. The orchestration is rich and varied, a broad palette allowing Ives to paint a detailed and atmospheric portrait of the day’s events.

The piece opens with music that symbolises ‘the awakening of memory,’ inviting listeners into the composer’s nostalgic reverie. As the movement unfolds, Ives ingeniously weaves together fragments of familiar tunes. He transforms the rousing Marching Through Georgia into the more reflective Tenting on the Old Camp Ground, capturing the emotional complexity of the occasion. The bugle call Taps is poignantly paired with the hymn Nearer, My God, to Thee, underscoring the solemnity of the commemoration.

The music gradually builds to a surging drumbeat, signaling the transition from the cemetery back to town. The march concludes with the spirited melody of Second Regiment, evoking the communal return and the lingering resonance of memory and tribute. Although composed in 1912, Decoration Day was not published until 1989. Today, it stands as a deeply personal and historically resonant work, offering a window into both Ives’ own past and the collective memory of a nation honouring its fallen.

Leave a comment