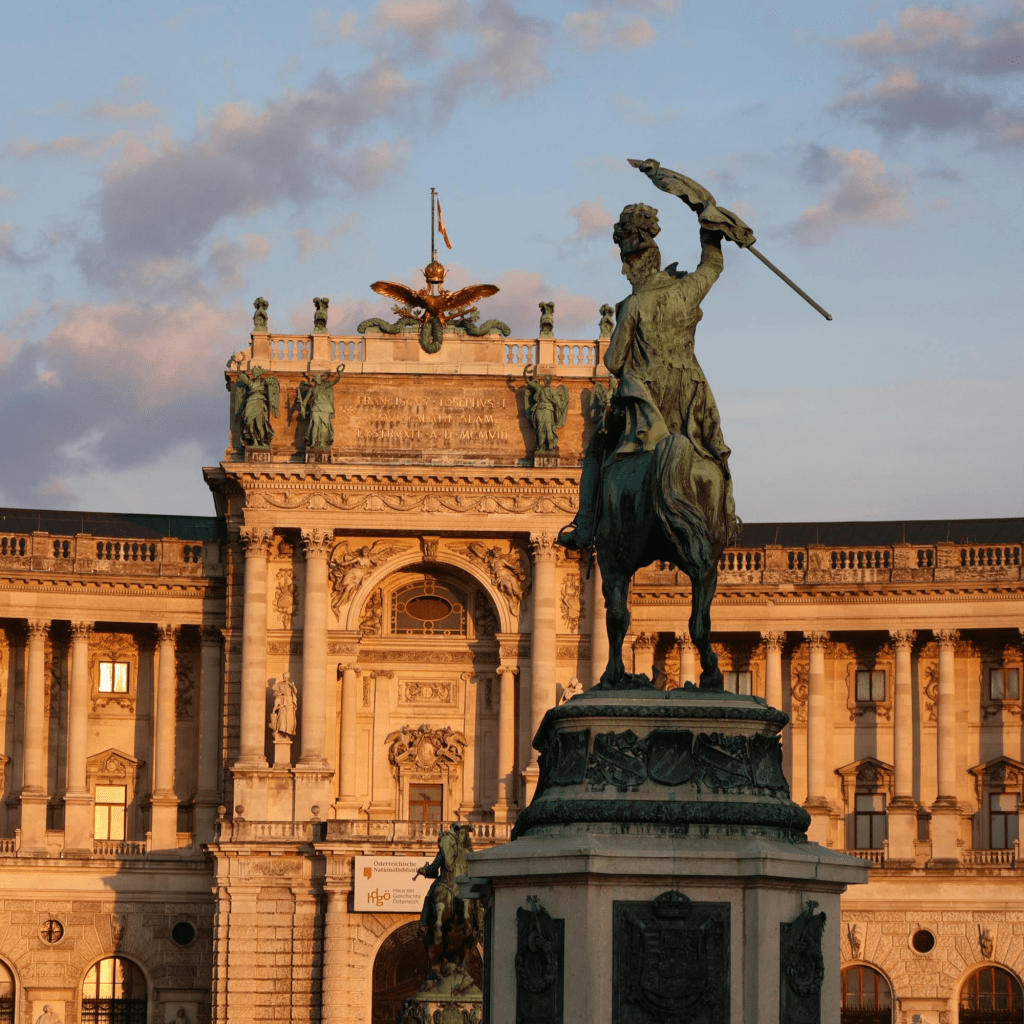

In the early years of the 20th century, Vienna stood as one of Europe’s great musical capitals – a city alive with energy, curiosity, and change. The legacy of Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn, Schubert, and Brahms still shaped its musical identity, while new voices began to redefine its sound. The grand stages of the Vienna State Opera, the Musikverein, the Konzerthaus, and the Volksoper regularly hosted performances that blended artistry with accessibility, drawing audiences from all corners of society. A growing urban middle class and flourishing intellectual life inspired the spread of music education, concert societies, and salons. Jewish composers, conductors, and performers contributed profoundly to this cultural vitality, even as antisemitism cast a troubling shadow. In this extraordinary moment, Vienna balanced reverence for its classical heritage with an appetite for innovation, giving birth to bold modern movements that mirrored the shifting spirit of a rapidly changing world.

Joseph Marx (1882-1962)

Symphony Movt I (1921)

Graz Philharmonic Orchestra

Johannes Wildner (conductor)

Franz Schreker (1878-1934)

Chamber Symphony (1916) III. Scherzo

Bochumer Symphony Orchestra

Stephen Sloane (conductor)

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No 4 (1900) I. Bedächtig, nicht eilen

Budapest Symphony Orchestra

Ivan Fischer (conductor)

Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937)

Third Symphony in Bb Major Op. 27 (1916) I. Song of the Night

London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus

Valery Gergiev (conductor).

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957)

Sinfonietta in B major Op 3 (1912) III. Allegro giocoso (1912-1913)

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra

Matthias Bamert (conductor)

Joseph Marx (1882-1962)

Symphony Movt I (1921)

Many composers whose voices were muted or forgotten amid the early twentieth century’s fierce debates over tonality are now being heard again. With that old conflict long gone, audiences can take equal pleasure in both the music of Berg and Korngold without hesitation. The revival of figures such as Schreker, Zemlinsky, and Korngold has reshaped the view of twentieth‑century music and broadened the emotional and stylistic range of 21st Century concert repertoire. Among these renewed voices, the Austrian composer Joseph Marx (1882–1964) stands out as a figure of great individuality and depth.

Marx was one of the central personalities of inter‑war Vienna – a respected teacher of composition, the founding rector of the city’s first Hochschule für Musik, and a prominent critic. His outspoken views, particularly his rejection of the Second Viennese School, made him a controversial figure, yet his music remained untouched by dogma. Instead, he pursued a personal synthesis that balanced Romantic warmth with the shimmering colour and sensual harmony of Impressionism.

In Eine Herbstsymphonie (Autumn Symphony), Marx captured this blend at its most compelling. Throughout, his orchestration glows with radiant textures, enriched by gently fluctuating harmonies that evoke the beauty and impermanence of the season. Marx’s symphony belongs to the same visionary lineage as Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, Vaughan Williams’s Sea Symphony, von Hausegger’s Natursinfonie, and Zemlinsky’s Lyrische Sinfonie – vast works that explore humanity’s relationship with nature and existence itself. For Marx, Autumn was both a symbol of transience and a celebration of renewal. The closing pages of Eine Herbstsymphonie do not mourn what fades but affirm the serenity, wisdom, and rightness of Nature’s eternal cycle.

Franz Schreker (1878-1934)

Chamber Symphony (1916) III. Scherzo

Nestled within Vienna’s illustrious musical tradition, Franz Schreker’s Chamber Symphony emerges as a concise masterpiece, condensing the expressive scope of a full symphony into a single 25-minute movement brimming with vivid colour and sensuality. At its core, the Scherzo surges with energy, revealing Schreker’s consummate skill in orchestral texture and profound psychological nuance.

Schreker’s life echoed this very intensity – a narrative of innovation tempered by tragedy. Born in 1878 in Monaco to a Bohemian Jewish father and an Austrian Catholic mother, he moved to Vienna in childhood and refined his artistry at the Conservatory under Robert Fuchs, studying violin and composition. His early compositions captivated listeners with their romantic orchestration and fervent emotion. The 1912 opera Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound) launched him to acclaim, succeeded by Die Gezeichneten (1918) and Der Schatzgräber (1920), which established him as a preeminent voice of his time.

In 1920, Schreker assumed directorship of Berlin’s Musikhochschule, where he nurtured talents including Ernst Krenek and Paul Hindemith. His music artfully merged Romantic passion, Impressionist allure, and Expressionist introspection, conjuring dreamlike domains in which sound and symbolism intertwine.

Composed in 1916 for the Vienna Music Academy’s centenary, the Chamber Symphony captures Schreker’s love for rich instrumental colors and smooth transformations. Scored for a compact ensemble of 24 players – winds, brass, harp, piano, celesta, harmonium, percussion, and strings – it flows through linked sections: lyrical moments give way to thoughtful pauses and lively rhythms, with the radiant Scherzo at its center. Themes shift effortlessly between instruments, creating an intimate yet expansive tapestry of sound. Derived from his abandoned opera Die tönenden Sphären (The Sounding Spheres), the work encapsulates Schreker’s conception of music as a sensual, metaphysical realm. Premiered in Vienna in 1917 under his own direction, it remains one of his most treasured concert works—a radiant bridge between the corporeal and the transcendent amid Vienna’s luminous era of sound.

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No 4 (1900) I. Bedächtig, nicht eilen

Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 stands as one of his most luminous and approachable works – a musical vision of innocence and wonder that looks toward the peace of heaven rather than the turmoil of earth. Its first movement sets the stage with calm assurance and gentle clarity.

Gustav Mahler was born in 1860 in Kaliště, Bohemia, the child of a Jewish innkeeper in a family of twelve. Gifted from childhood, he entered the Vienna Conservatory at fifteen, dreaming of becoming a composer but soon excelled as a conductor. His extraordinary artistry led him to posts in Leipzig, Budapest, Hamburg, and Vienna, where, as director of the Court Opera, he raised musical standards to new heights. Later, his restless spirit brought him to New York, where he conducted both the Metropolitan Opera and the Philharmonic.

Mahler’s symphonies chart vast emotional landscapes – combining philosophical reflection, human drama, and transcendence. Composed between 1899 and 1900, the Symphony No 4 is lighter in texture and more intimate in character than his monumental predecessors. The opening movement, Bedächtig, nicht eilen, unfolds with serene deliberation, bright harmonies, and the delicate chime of sleigh bells. Mahler frames the symphony as a child’s vision of heaven, culminating in the finale’s song Das himmlische Leben (The Heavenly Life).

Where his earlier symphonies grapple with cosmic struggle, the Fourth offers a sense of acceptance and quiet joy – a distillation of Mahler’s humanism through simplicity and grace. Its première in Munich in 1901 met mixed reactions, but it has since become one of his most beloved works for its warmth, lyricism, and spiritual light

Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937)

Third Symphony in Bb Major Op. 27 (1916) I. Song of the Night

Karol Szymanowski was one of Poland’s most imaginative and distinctive composers, a figure whose music bridges the lush colours of late Romanticism with the mysticism of modernism. Born in 1882 in Tymoszówka – then part of the Russian Empire – he studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and soon emerged as a central figure of the Young Poland movement, which aimed to create a new national musical voice.

Szymanowski’s early music reflects the influence of composers such as Chopin, Wagner, and Scriabin, filled with rich harmonies and emotional intensity. Over time, his style evolved to embrace Impressionist colour, polytonality, and a unique melodic language inspired by Mediterranean, Islamic, and Polish folk traditions. His later fascination with the folk music of the Tatra highlanders (Górale) profoundly shaped works like the ballet Harnasie, his Symphony No. 4, and sets of Mazurkas for piano.

A tireless advocate for Polish culture, he founded the Young Polish Composers’ Publishing Company in Berlin and later served as director of the Warsaw Conservatory, reforming music education and promoting a distinctly Polish modernism. Despite fragile health, his later works such as the Violin Concerto No. 2 and Symphony No. 4, represent a synthesis of national spirit and cosmopolitan modernity.

Composed during the First World War, Szymanowski’s Symphony No. 3 in B-flat major, Song of the Night (1916) stands as one of his most inspired creations. Scored for solo tenor, chorus, and orchestra, it is based on a mystical poem by the 13th‑century Persian poet Rumi, translated into Polish by Tadeusz Miciński. Written as a single, continuous movement (often divided into three broad sections), the symphony unfolds like a nocturnal vision, blending the sensual and the spiritual.

Its sound world reflects influences from Scriabin and Wagner while expressing a uniquely personal mysticism. Premiered in 1928 in Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine), Song of the Night remains one of Szymanowski’s grandest and most ravishing testaments to the magic of sound and spirit.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957)

Sinfonietta in B major Op 3 (1912) III. Allegro giocoso (1912-1913)

Erich Wolfgang Korngold was one of the most extraordinary musical prodigies of the 20th century – a bridge between the glittering late Romantic world of Vienna and the golden age of Hollywood. Born in 1897 in Brno, then part of Austria-Hungary, he showed remarkable musical gifts from an early age. By eleven, he had composed a ballet, Der Schneemann, that created a sensation when performed at the Vienna Court Opera.

Mentored by Gustav Mahler and admired by Richard Strauss and Giacomo Puccini, Korngold’s teenage years were filled with astonishing successes. His operas Violanta and Die tote Stadt confirmed his mastery of melodic invention and orchestral colour, blending Viennese romanticism with emotional directness. Though still a youth, he was already recognized as one of Europe’s most gifted composers.

When the rise of Nazism forced him to flee Austria in the 1930s, Korngold settled in Hollywood, where his lush, symphonic style transformed film music. He became one of the first classical composers to win major acclaim in the movie industry, creating scores such as The Adventures of Robin Hood (for which he won an Academy Award) and The Sea Hawk. His sweeping melodies and noble harmonies shaped the sound of cinema for decades to come.

Composed at just fourteen, the Sinfonietta in B major, Op. 3, reveals the prodigious technique and passionate energy that would define Korngold’s later music. Premiered by Felix Weingartner and the Vienna Philharmonic in 1913, it enjoyed immediate success across Europe and America. Despite its diminutive title, the work is symphonic in scope, sumptuous in orchestration, radiant in tone, and rich with youthful optimism.

The third movement, Allegro giocoso, bursts with vitality and brilliance. Throughout the Sinfonietta, a five-note ascending motif – the ‘Happy Heart’ theme – serves as a unifying thread, symbolising in enthusiasm and confidence. Korngold’s vast orchestra, complete with piano, celesta, two harps, and a vivid percussion section, creates a dazzling sonic palette reminiscent of Mahler and Strauss.

The Sinfonietta marks the dawn of Korngold’s orchestral genius, capturing the joy and exuberance of youth in a work that glows with warmth, melodic richness, and a spirit of boundless promise.

Mahler, Marx, Schreker, Szymanowski, and Korngold all lived at a time when music was changing. Each, in their own way, searched for beauty and meaning in a world moving from the Romantic era into modern times. Though their voices were different, they shared a love of melody, emotion, and imagination. Their music reminds us that even in times of great change, art continues to express what endures – our longing, our spirit, and our faith in the power of beauty.

Leave a comment