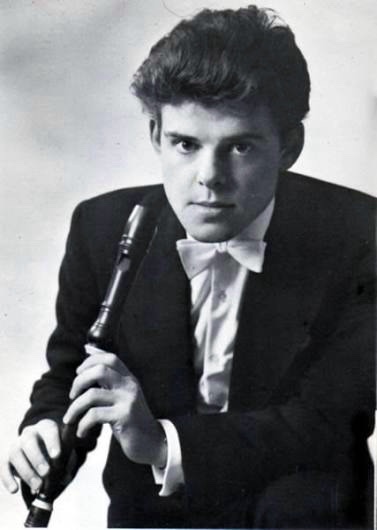

In the 1970s, one voice transformed young people’s understanding of music. David Munrow, musician, scholar and broadcaster, presented Pied Piper: Tales and Music for Younger Listeners on BBC Radio 3 between 1971 and 1976. Over 655 episodes, he introduced a generation to everything from Bach to brass bands, medieval songs to electronic music. Though nominally a children’s show, its wit and range captured adult imaginations too, with an average listener age of 29. Munrow possessed a rare blend of enthusiasm, intellect and accessibility. He spoke with clarity, never overwhelming his audience, always letting the music breathe. His storytelling hooked listeners, as when he began an episode on Sir Thomas Beecham by weaving trivia and curiosity into irresistible narrative. In every broadcast, he revealed both breadth of knowledge and an unpretentious love of discovery.

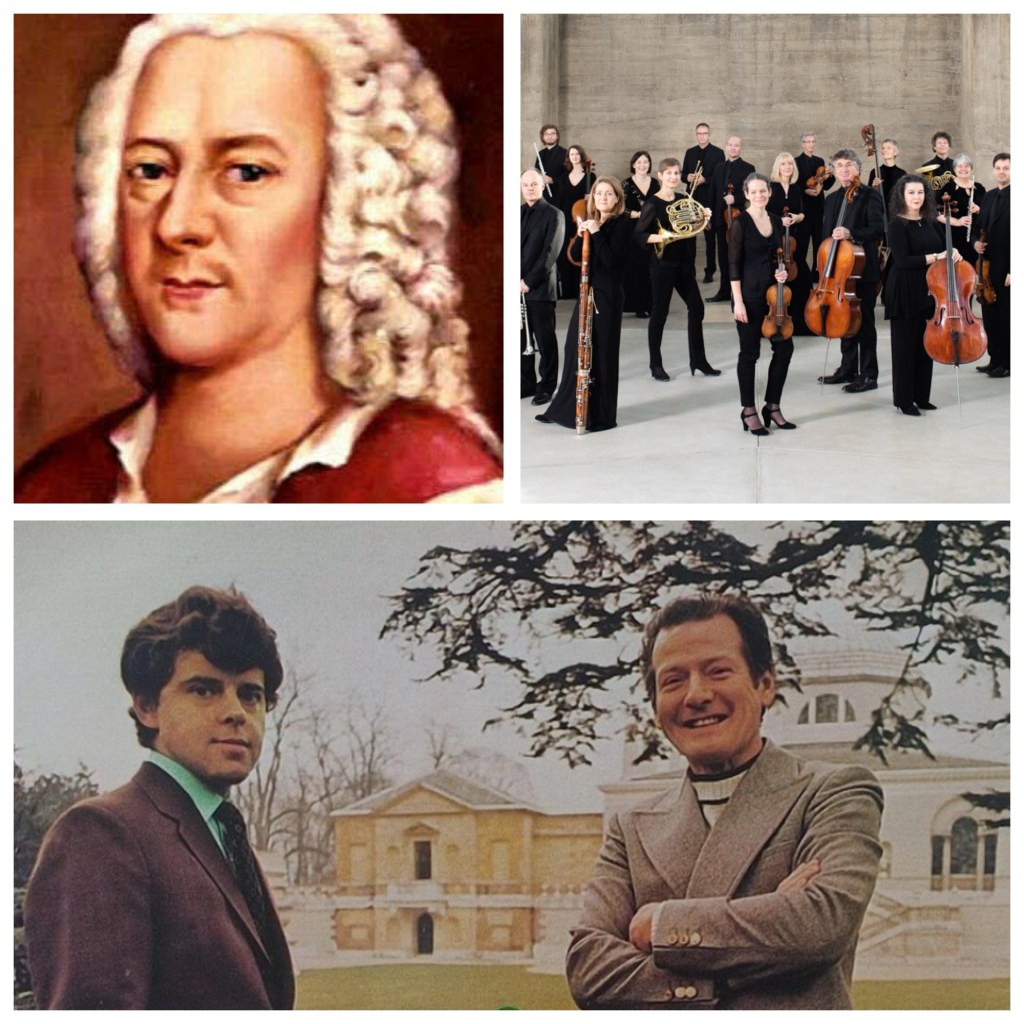

George Philip Telemann (1681-1767)

Rejouissance from Ouverture‑Suite in A minor (TWV 55:a2)

Academy of St-Martin’s-in-the-Fields

David Munrow (Treble Recorder)

Neville Marriner (conductor)

Borlet (late 14th and early 15th centuries)

Ma tredol roussignoi (early 15th century)

The Early Music Consort of London

David Munro (director)

Michael Praetorius (1571-1621)

Dances of Terpsichore: Suite des voltes (1612)

The Early Music Consort of London

David Munro (director)

Attributed to Josquin des Prez (1450 to 1455-1521)

Scaramella va alla guerra

The Early Music Consort of London

David Munro (director)

Tyman Susato (1510 to 1515-1570)

The Dansyrie: La Bataille (1551)

The Early Music Consort of London

David Munro (director)

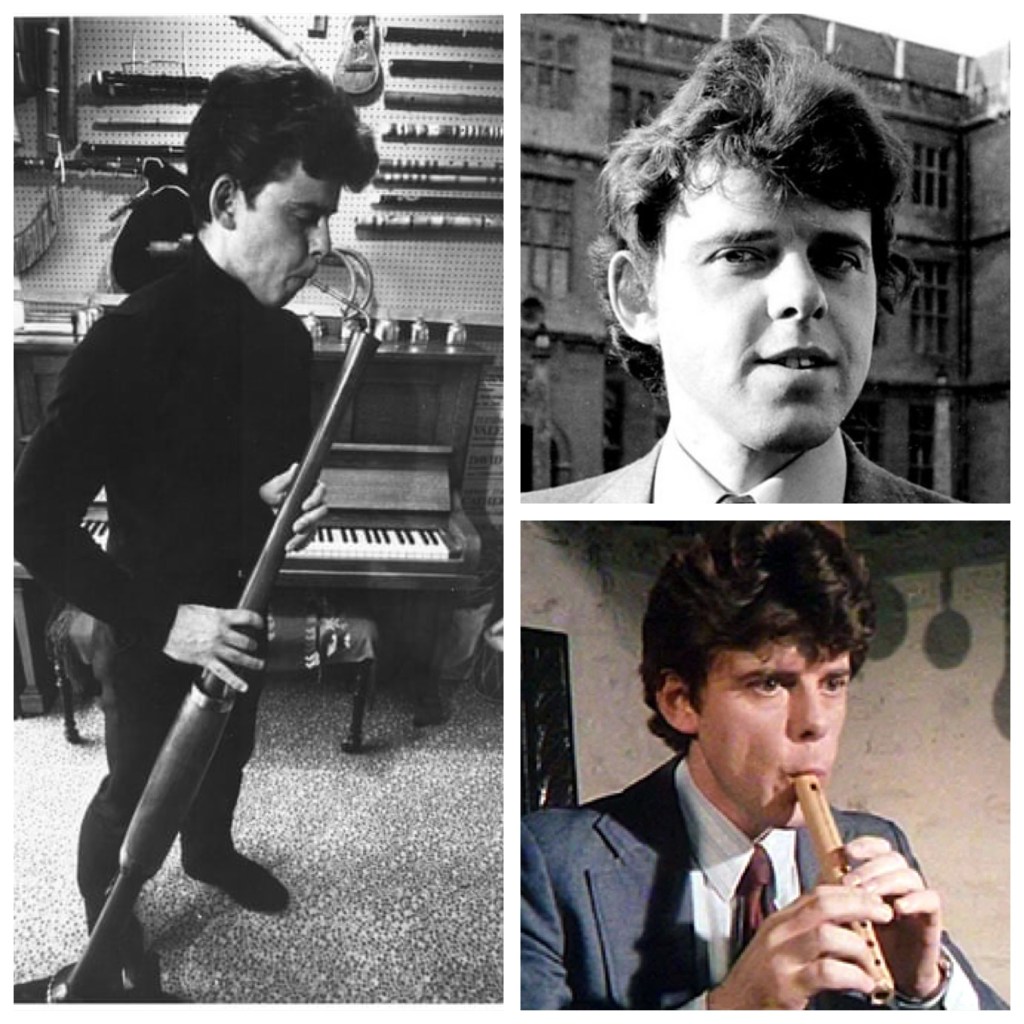

That love began early. As a schoolboy he taught himself bassoon in two weeks before heading to Peru, where he explored indigenous instruments, later reading at Cambridge in the 1960s. It was there he first encountered a crumhorn – an encounter that changed his life. Fascinated by the sounds of the past, he went on to master more than forty early instruments and channel that fascination into performance and research.

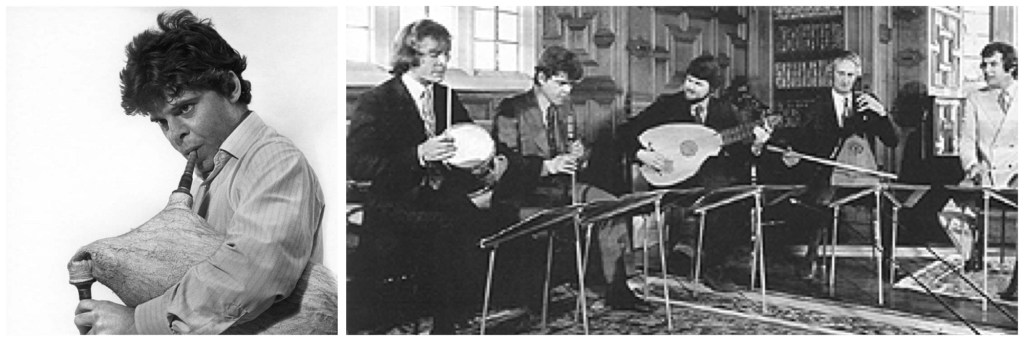

In 1967 he founded the Early Music Consort of London with Christopher Hogwood. Their recordings—more than fifty within a decade – revolutionised attitudes to medieval and Renaissance music. Munrow’s fresh, experimental approach made ancient sounds feel as alive as rock or jazz, winning audiences far beyond the traditional classical sphere. His album projects and soundtracks (including The Six Wives of Henry VIII and Zardoz) redefined early music’s place in modern culture.

Tragically, Munrow’s life ended in 1976 when he was only 33. Yet his twin legacies – as a pioneering early musician and a brilliant broadcaster – continue to shape how music is presented, taught and imagined today. Music, thanks to him, became a larger and more adventurous universe.

Neville Marriner (conductor)

George Philip Telemann (1681-1767)

Rejouissance from Ouverture‑Suite in A minor (TWV 55:a2)

Telemann was admired across Europe for his ‘mixed taste’ (vermischter Geschmack), a style that blended French elegance with Italian brilliance. The Ouverture‑Suite, modelled on the grand French orchestral suite, begins with a stately overture and continues through a series of contrasting dances, including the Menuet, Les Plaisirs, and Polonaise. Telemann enriches this framework with the verve and virtuosity of the Italian concerto, giving the soloist an arresting presence throughout.

The work was originally intended for the flauto – the Baroque treble (or alto) recorder – an instrument Telemann played himself. Its solo part perfectly suits the recorder’s nimble technique and expressive range, filled with breathless runs, arpeggios, and dynamic exchanges with the orchestra. Munrow’s vivid playing in this recording brings out both the instrument’s lyrical voice and its dazzling agility, qualities that made him such a pioneer of early‑music performance.

In the Réjouissance, Telemann creates a radiant finale that lives up to its name. Speed, precision, and elegance combine in a celebration of joy, where virtuosic passages alternate with moments of buoyant grace. Beneath its brilliance lies a lightness of touch – an example of Baroque galanterie – in which good humour, polish, and musical wit take centre stage. It is no wonder that performances like this continue to embody the enduring charm and vitality of Telemann’s art.

Borlet (late 14th and early 15th centuries)

Ma tredol roussignoi (early 15th century)

In the closing years of the 14th century and the dawn of the 15th, European music was undergoing a remarkable metamorphosis. Within this climate of invention appeared the elusive figure of Borlet, a composer wrapped in mystery and conjecture. Virtually nothing is known of his life, and even his identity remains uncertain – his name may be an anagram of ‘Trebol,’ a French musician who served King Martin of Aragon around 1409. If the connection is true, Borlet would have belonged to one of the most imaginative and cosmopolitan courts of his age.

Borlet’s surviving music is exquisitely rare, and its rediscovery owes much to the scholarship and advocacy of David Munrow and The Early Music Consort of London. Through their landmark recording of Ma tre dol roussignol, Munrow introduced audiences worldwide to Borlet’s refined artistry, ensuring that a composer who might otherwise have vanished entirely from musical memory was heard once more. The performance captures the lyrical grace and rhythmic subtlety of Borlet’s style – the intricate interplay of melody and rhythm that typifies the late medieval Ars Subtilior. In Munrow’s hands, this delicate virelai emerges not as a historical fragment but as a living, breathing song of rare emotional depth and fluid beauty.

Borlet’s music belongs to a moment of transformation in Western composition, poised between the rhythmic complexity of the Ars Nova and the smoother sonorities of the early Renaissance. His songs mirror a world searching for balance between intellect and expression, structure and sensibility. Thanks to David Munrow’s inspired direction, that world now speaks again with clarity and grace – a fragile echo from the past, brought vividly to life for modern ears through one of the most important early music revivals of the 20th century.

Michael Praetorius (1571-1621)

Dances of Terpsichore: Suite des voltes (1612)

Few composers embody the spirit of musical invention in early seventeenth-century Germany as vividly as Michael Praetorius (1571–1621). A composer, organist, and theorist of astonishing versatility, Praetorius bridged the musical worlds of Renaissance polyphony and the emerging Baroque. The youngest son of a Lutheran minister from Creuzburg in Thuringia, he grew up immersed in sacred song and humanist learning. His studies at the University of Frankfurt (Oder) honed his command of languages, theology, and music – skills that later infused both his compositions and his monumental treatise, Syntagma musicum, one of the era’s most detailed guides to musical practice and instrumentation.

Praetorius’s career took him from the organ loft of the Marienkirche in Frankfurt (Oder) to the court of Duke Heinrich Julius of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, where he eventually served as Kapellmeister. His exposure to the resplendent polychoral style of Venice during his time in Dresden profoundly influenced his sacred works, while his secular output reveals a cosmopolitan ear attuned to European fashions. Among his vast catalogue, Musae Sionia – a compendium of over 1,200 chorale arrangements – attests to his devotion to Protestant hymnody, while Terpsichore (published 1612) celebrates the exuberance of courtly dance.

Terpsichore, Musarum Aoniarum Quinta comprises 312 dance pieces, many drawn from contemporary French sources brought to the Wolfenbüttel court by the dancing master Antoine Emeraud. These lively bransles, courantes, and voltes – such as the spirited Suite des voltes—were arranged for instrumental ensembles of violins and lutes, offering an invaluable glimpse into early 17th-century dance music. The volte, with its buoyant triple meter and flirtatious energy, epitomizes the elegance and wit of the French court.

Modern audiences owe much of their awareness of this repertoire to David Munrow and The Early Music Consort of London, whose 1970s recordings of Terpsichore brought Praetorius’s dances to vivid life. Munrow’s trailblazing interpretations helped ignite worldwide interest in early music and revealed Praetorius as not just a scholar’s figure, but a composer of irresistible rhythmic vitality and charm.

Attributed to Josquin des Prez (1450 to 1455-1521)

Scaramella va alla guerra

Few names in Renaissance music command such reverence as Josquin des Prez (c.1450/55–1521). Born in the region straddling modern-day France and Belgium, Josquin rose from the Franco-Flemish school to become the most celebrated composer of his age. During his lifetime, he served in some of Europe’s most prestigious musical establishments – the Sforza court in Milan, the papal chapel in Rome, and later, the d’Este court in Ferrara – before concluding his career as provost of the collegiate church of Notre Dame in Condé-sur-l’Escaut. His music was among the first to be widely published through the new technology of printing, ensuring that his influence spread across the continent.

Josquin’s genius lay in his profound sense of musical expression. In his sacred works – the great masses and motets such as Ave Maria… Virgo serena and Miserere mei, Deus – he united intricate counterpoint with an unprecedented sensitivity to the meaning and rhythm of words. Yet amid his lofty religious works, he also revealed a more human, humorous voice in his secular songs.

Scaramella va alla guerra (Scaramella goes to war) is one such piece: a lively, witty chanson set for four voices, brimming with rhythmic energy and earthy charm. The song paints a comic portrait of Scaramella, a hapless braggart soldier toddling off to battle, capturing the exaggerated style of popular Italian street song. Its tightly woven imitative textures and rhythmic bounce show Josquin’s ability to bring refinement to seemingly simple material.

Rediscovered by modern performers, Scaramella gained new life in the 1970s through David Munrow and The Early Music Consort of London, whose landmark recordings illuminated the vitality of Renaissance secular music. Munrow’s vivid interpretations introduced listeners to the playfulness and colour of Josquin’s lighter works, restoring them to the living repertoire and transforming how early music was heard and understood.

Tyman Susato (1510 to 1515-1570)

The Dansyrie: La Bataille (1551)

In the cultural flourishing of sixteenth-century Antwerp, few figures embodied the spirit of musical enterprise as brilliantly as Tielman Susato (c.1510–1570). A composer, instrumentalist, and pioneering music publisher, Susato helped shape the soundscape of the Northern Renaissance. Born probably in Soest, he settled in Antwerp by 1529, where he played in the city’s civic band and developed his skills as a calligrapher and instrumentalist on trumpet, sackbut, and recorder.

In 1543, Susato established his publishing house At the Sign of the Crumhorn, the first of its kind in the Low Countries. Using newly developed movable type, he printed music by leading composers of his day – Josquin des Prez, Orlando di Lasso, and Jacob Clemens non Papa among them – making sacred and secular polyphony more widely available than ever before. His press became a beacon for the exchange of musical styles within Renaissance Europe.

Susato was not only a publisher but also a creative composer. His Danserye (1551), a collection of pavans, galliards, and other popular dance forms, stands as one of the great anthologies of Renaissance instrumental music. Among its most famous pieces, La Bataille (The Battle Pavane), evokes the spectacle of ceremonial warfare through rhythmic trumpet calls, dotted fanfares, and stately harmonic progressions. Written in the noble pavane style, it blends martial character with grace and balance – music that captures both pageantry and power.

Originally performed by consorts of shawms, sackbuts, cornets, and viols, La Bataille represents the civic and celebratory musical culture of mid-sixteenth-century Antwerp, where such processional pieces enlivened festivals, parades, and courtly occasions.

David Munrow and The Early Music Consort of London brought new life to this music with their spirited performances, revealing its rhythmic vitality and vivid colour. Under Munrow’s imaginative direction, La Bataille emerged not merely as a historical artefact but as a dynamic, resounding evocation of Renaissance ceremony – music that continues to captivate listeners five centuries on.

The Legacy of David Munrow

As the programme has reminded us, much of the music we now celebrate from the medieval and Renaissance worlds might have remained silent had it not been for the extraordinary vision of David Munrow. His passionate musicianship and boundless curiosity transformed early music from an academic niche into a living, breathing art form that continues to inspire performers and audiences alike.

Munrow combined scholarly insight with contagious enthusiasm. With colleagues including Christopher Hogwood, James Bowman, and Robert Spencer, he brought authenticity and vitality to instruments long forgotten – shawms, crumhorns, sackbuts, rebecs – reviving their voices with flair and conviction. His 1976 book Instruments of the Middle Ages and Renaissance remains a cornerstone of musicological study, complementing his artistry with scholarship of lasting depth.

Tragically, Munrow’s brilliant career ended with his untimely death in 1976 at the age of 33. More than forty years on, the recordings of The Early Music Consort of London continue to astonish with their colour, rhythmic joy, and immediacy. Through them, La Bataille, Terpsichore, and countless other rediscovered treasures speak anew. These performances stands as both tribute and testament – to a musician whose energy and imagination bridged time itself, bringing the past vividly, triumphantly into the present.

Leave a comment