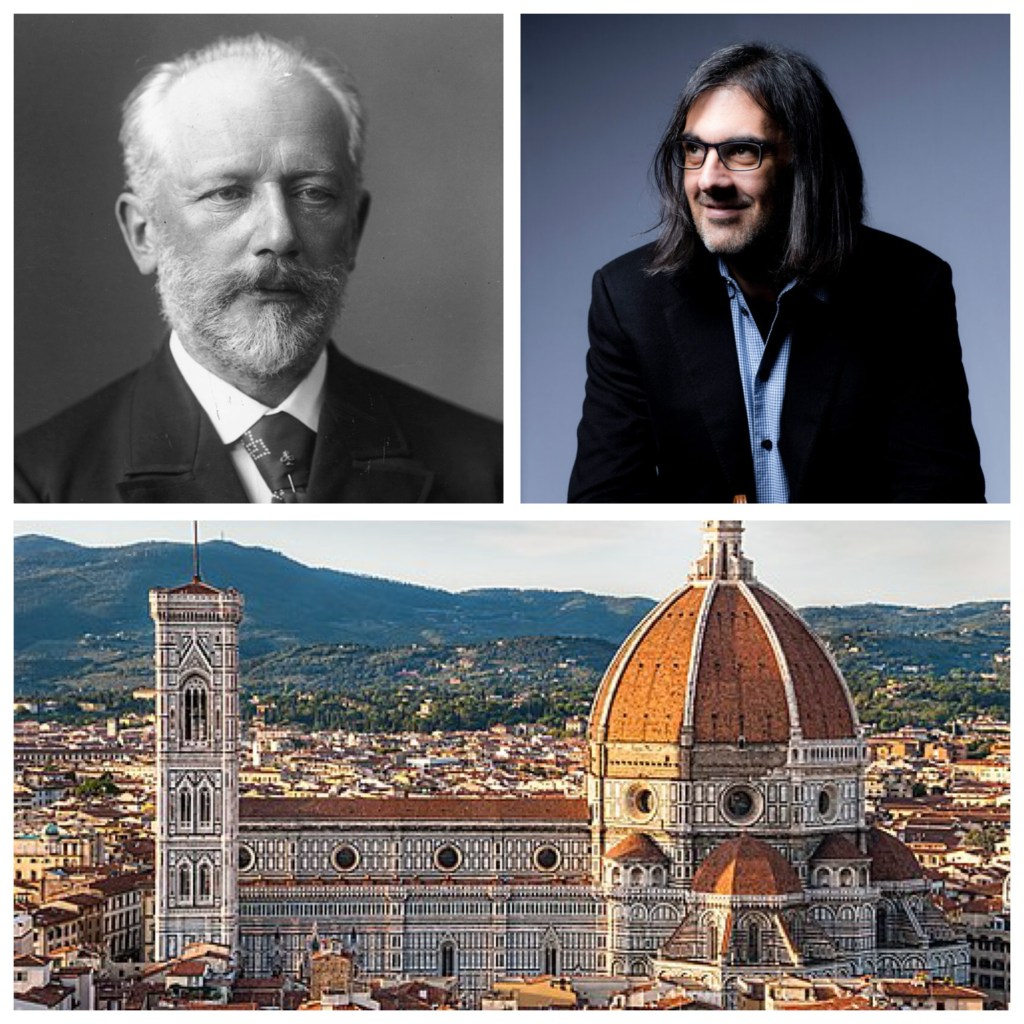

While Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky is loved worldwide for Swan Lake, The Nutcracker, and his great concertos, his catalogue holds many pieces that deserve renewed attention. Works such as Souvenir de Florence, Op. 70, display his mastery of chamber textures and his gift for lyrical melody, whilst Hamlet, Op. 67a, and the evocative Tempest, reveal his fascination with dramatic narrative. The Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 17, nicknamed the ‘Little Russian,’ brims with folk vitality, and the Concert Fantasia for piano and orchestra, Op. 34, demonstrates his flair for virtuosic innovation beyond the traditional concerto form. Together, these lesser-known works reveal just how imaginative Tchaikovsky was. His music moves easily from deep, personal emotion to sweeping drama, inviting listeners to rediscover a composer with endless creative spirit.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Souvenir de Florence, Op. 70 (1890) (IV. Allegro vivace) for string sextet

Leonidas Kavakis Quartet

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

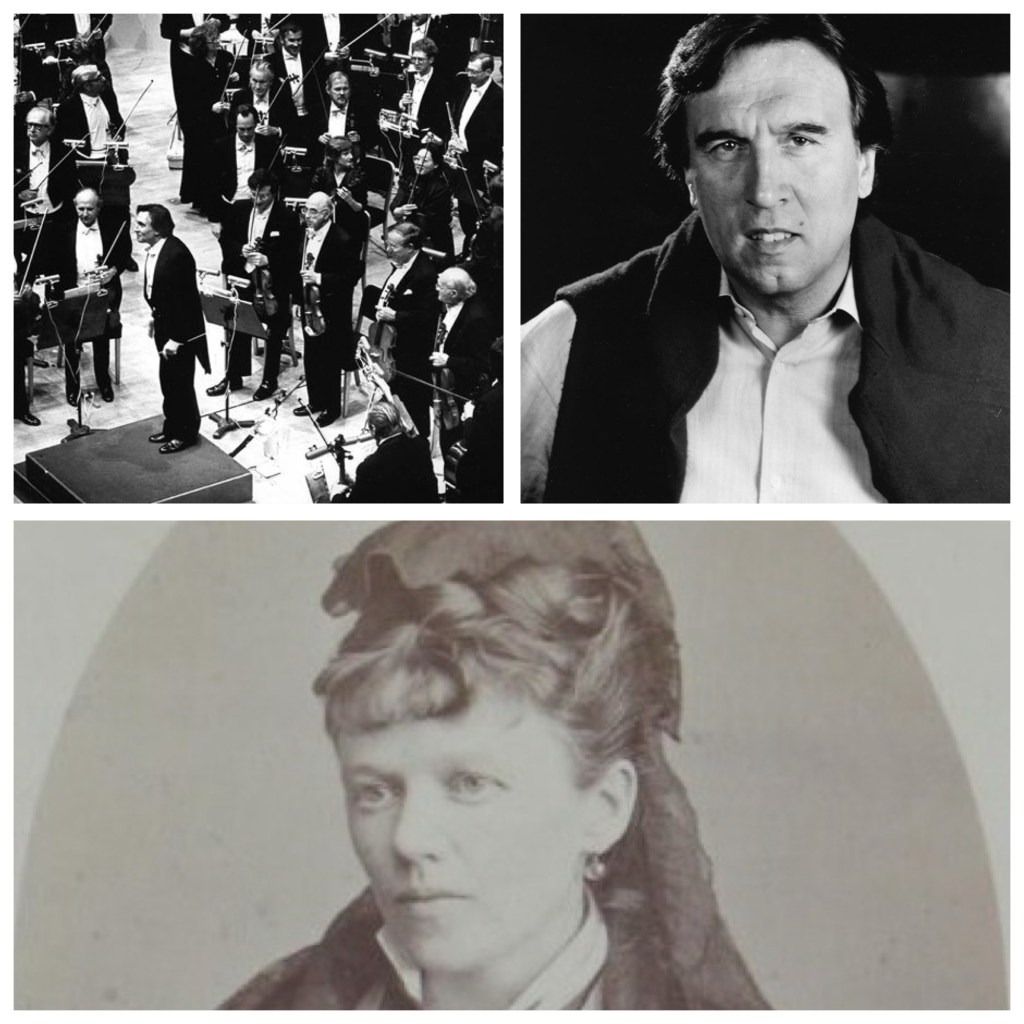

Hamlet, Op. 67a; Fantasy Overture (1888)

New York Philharmonic

Leonard Bernstein (conductor)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Concert Fantasia for piano and orchestra, Op. 34 (1884)

Eldar Nebolsin (piano

New Zealand Symphony Orchestra

Michael Stern (conductor)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

The Tempest (Oberon) Overture (1873)

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

Andrew Litton (conductor)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 17 ‘Little Russian’ (1872)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Claudio Abbado (conductor)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) was born in Votkinsk, Russia. Initially trained in law, he left the civil service to study at the St Petersburg Conservatory, where his lyrical, expressive style quickly emerged. His ballets Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, and The Nutcracker transformed ballet music, while operas such as Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades revealed his profound melodic gift. Despite personal struggles, his music radiated emotional sincerity and imagination. Celebrated internationally as both composer and conductor, Tchaikovsky crowned his career with the Symphony No. 6 (‘Pathétique’), a deeply moving farewell that immortalised his status as one of Russia’s greatest musical voices.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Souvenir de Florence, Op. 70 (1890) (IV. Allegro vivace) for string sextet

Composed in the summer of 1890, Souvenir de Florence a unique place in Tchaikovsky’s output as his only work for string sextet – two violins, two violas, and two cellos. He dedicated it to the St Petersburg Chamber Music Society upon being named an honorary member, offering it both as a gesture of gratitude and a heartfelt tribute to the intimacy of chamber music. The title recalls Florence, where he first sketched one of its main themes while working on the opera The Queen of Spades.

Tchaikovsky’s time in Italy had been a rare moment of calm and creative renewal, and the sextet reflects something of that warmth and vitality. Within its four movements, he combines the brilliance of his symphonic writing with the conversational spirit of chamber music. Revised between December 1891 and January 1892, the piece challenged Tchaikovsky’s fear of writing for smaller ensembles after his years devoted to large theatrical works. Yet its brilliance lies in how effortlessly he fuses Italian lyricism with Russian fervour, creating music that is at once elegant, playful, and deeply expressive. Later arranged for string orchestra and occasionally adapted for ballet, Souvenir de Florence remains one of Tchaikovsky’s most captivating chamber works – a celebration of melody, sunlight, and the joy of making music in its purest form.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Hamlet, Op. 67a; Fantasy Overture (1888)

Tchaikovsky’s Hamlet Overture‑Fantasia was composed in 1888, inspired by Shakespeare’s great tragedy and dedicated to the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg. Written and orchestrated between June and October of that year, the work belongs to the same fertile creative period as his Fifth Symphony, combining the composer’s mature Romantic style with an instinctive feel for dramatic storytelling.

Scored for a large symphony orchestra—complete with full woodwinds, brass, percussion, and strings—the overture unfolds in a single continuous movement lasting around twenty minutes. Its two main sections, Lento lugubre and Allegro vivace, trace an emotional arc from darkness to defiance. From the opening bars, low strings and sombre harmonies conjure the shadowed halls of Elsinore Castle and the restless mind of the Danish prince. The brooding main theme, emblem of Hamlet’s inner torment, contrasts poignantly with a tender, fragile oboe melody representing Ophelia. A passionate love theme and a martial motive connected with Fortinbras add further dimensions to the psychological landscape.

Rather than attempting a literal retelling of Shakespeare’s plot, Tchaikovsky sought to capture its emotional and moral essence: the conflict between reflection and action, love and betrayal, reason and despair. The music builds to a blazing climax symbolizing the fatal duel and the collapse of the royal house, before fading into quiet resignation.

Tchaikovsky later revisited the score in 1891 when composing incidental music (Op. 67a) for a Petersburg stage production of Hamlet, re‑shaping material from the overture into shorter movements. Together with his Romeo and Juliet and The Tempest overtures, Hamlet reflects his deep empathy for Shakespeare’s characters and his gift for translating their psychological struggles into symphonic drama of profound intensity.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Concert Fantasia for piano and orchestra, Op. 34 (1884)

Composed in 1884, Tchaikovsky’s Concert Fantasia for piano and orchestra occupies an unusual place in his output. Neither a traditional concerto nor a set of variations, it is a free-form work that explores new ways of balancing piano and orchestra. Tchaikovsky viewed the concerto genre with ambivalence – fascinated by its possibilities, yet wary of the tendency for soloist and orchestra to compete rather than collaborate. In the Fantasia, he sought a more integrated partnership, letting ideas and emotions flow between the players in a continuous musical narrative.

The piece, dedicated to the virtuoso pianist (and Liszt pupil) Sophie Menter, displays dazzling keyboard writing within a richly coloured orchestral frame of woodwinds, brass, percussion, and strings, including touches of tambourine and glockenspiel for added sparkle. It lasts around half an hour and unfolds in two connected movements: Quasi Rondo and Contrastes.

Lushly orchestrated and deeply Romantic in spirit, the Concert Fantasia offers both intimate expression and dazzling virtuosity. Though less frequently performed than his concertos, it stands as one of Tchaikovsky’s most original creations for piano and orchestra – an expressive experiment where freedom, lyricism, and brilliance meet on equal ground. The composer later arranged the work for two pianos, further testament to his affection for its radiant musical qualities.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

The Tempest (Oberon) Overture (1873)

In the early 1870s, Tchaikovsky was emerging as one of Russia’s most gifted young composers. Fresh from the success of his Romeo and Juliet fantasy‑overture, he was searching for another subject that combined drama, poetry, and emotional depth. The idea came from Vladimir Stasov, a leading critic and champion of the ‘Mighty Handful,’ who encouraged Russian composers to create works rooted in national culture yet inspired by great literature. Stasov suggested Shakespeare’s The Tempest and even outlined in detail how the story might be translated into music.

Tchaikovsky accepted eagerly, perhaps drawn to the play’s mixture of supernatural power, love, and reconciliation – qualities perfectly suited to his Romantic temperament. The commission for The Tempest came through Nikolai Rubinstein, conductor of the Moscow branch of the Russian Music Society, who requested a new piece for the forthcoming season. Tchaikovsky composed the score quickly during the summer of 1873 while on a peaceful retreat in the countryside, later recalling that the music seemed to flow effortlessly, ‘as though by some higher inspiration.’

The Fantasia was completed in October 1873 and premiered two months later in Moscow under Rubinstein’s direction to warm acclaim. Both Rimsky‑Korsakov and Stasov praised the work’s vividness and poise, noting how Tchaikovsky’s orchestral imagination captured the spirit of Shakespeare’s play without slavish imitation.

Although The Tempest is less frequently performed today than Romeo and Juliet, it marks an important turning point in Tchaikovsky’s development. It shows his growing confidence in symphonic narrative and his ability to marry Western Romantic ideals with distinctly Russian colour. The work also deepened his creative friendship with Stasov, who continued to suggest literary inspirations – including Hamlet later in his career.

Tchaikovsky cherished The Tempest for its sense of renewal and balance. Composed during one of the few truly contented periods of his life, it embodies both the storm and the calm – the emotional turbulence and serenity that came to define his most enduring music.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 17 ‘Little Russian’ (1872)

Tchaikovsky composed his Symphony No. 2 during the summer of 1872 while staying with his sister Aleksandra at her family’s estate in Kamenka, Ukraine. At the time, he was a young professor at the newly founded Moscow Conservatory, only recently finding his voice as a symphonist. Unlike his First Symphony, which had been an exhausting labour, this new work came together swiftly and with a growing assurance of style.

There was no formal commission for the symphony; rather, it was encouraged by the strong sense of national identity then flourishing among Russian composers. Tchaikovsky wanted to blend Western symphonic craft with authentically Russian melody, an ambition shared by the nationalist composers Balakirev, Mussorgsky, and Rimsky‑Korsakov. For this second symphony he turned to Ukrainian folksongs that he had heard during his summer stay. These rustic, memorable tunes – particularly the folk theme used in the finale – gave rise to the affectionate nickname ‘Little Russian,’ then a common term for Ukraine.

The symphony was first performed in Moscow on 26 January 1873 under Nikolai Rubinstein, a key figure in Tchaikovsky’s early career and a tireless champion of his music. The premiere was an immediate success, and even the usually cautious Balakirev praised the work warmly. Tchaikovsky later revisited the piece in 1879-80, tightening its structure and refining the orchestration. The revised version, first heard in 1881, is the one normally performed today.

Historically, the ‘Little Russian’ marked a turning point for Tchaikovsky. It demonstrated his ability to craft a large‑scale symphony that was both vividly national in colour and masterfully organized in form – traits that would culminate in his later symphonic masterpieces. With its exuberant use of Ukrainian folk tunes, rhythmic vitality, and radiant closing pages, the symphony captured the optimism of a composer beginning to find confidence and international promise.

Leave a comment