The Vienna Philharmonic’s New Year’s Day Concert endures as one of the city’s most cherished traditions – an exuberant tribute to waltzes, polkas, and 19th-century Viennese sparkle. Born in 1939 amid Austria’s annexation by Nazi Germany, it elevated the Strauss family – Johann I, Johann II, Josef, and Eduard – as symbols of ‘pure’ Viennese culture under propaganda’s shadow. After World War II, it blossomed into a global ritual, its origins softened while the Strausses reigned supreme.

Yet Viennese light music thrived beyond the Strauss dynasty. Joseph Lanner, Johann Strauss I’s contemporary and partner, elevated the waltz to symphonic grace. Carl Michael Ziehrer and Franz von Suppé breathed new life into operettas and dances, while Paris’s Émile Waldteufel and Germany’s Moritz Moszkowski enriched Europe’s ballroom repertoire with inventive charm.

By championing alternative composers, this programne honours the splendour, elegance, allure and vitality of the New Year’s Day concert – replacing tradition with innovation, whilst celebrating Vienna’s musical heritage.

Emmanuel Chabrier (1841-1894)

Fête polonaise from Le roi malgré lui (1887)

Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Paul Paray (conductor)

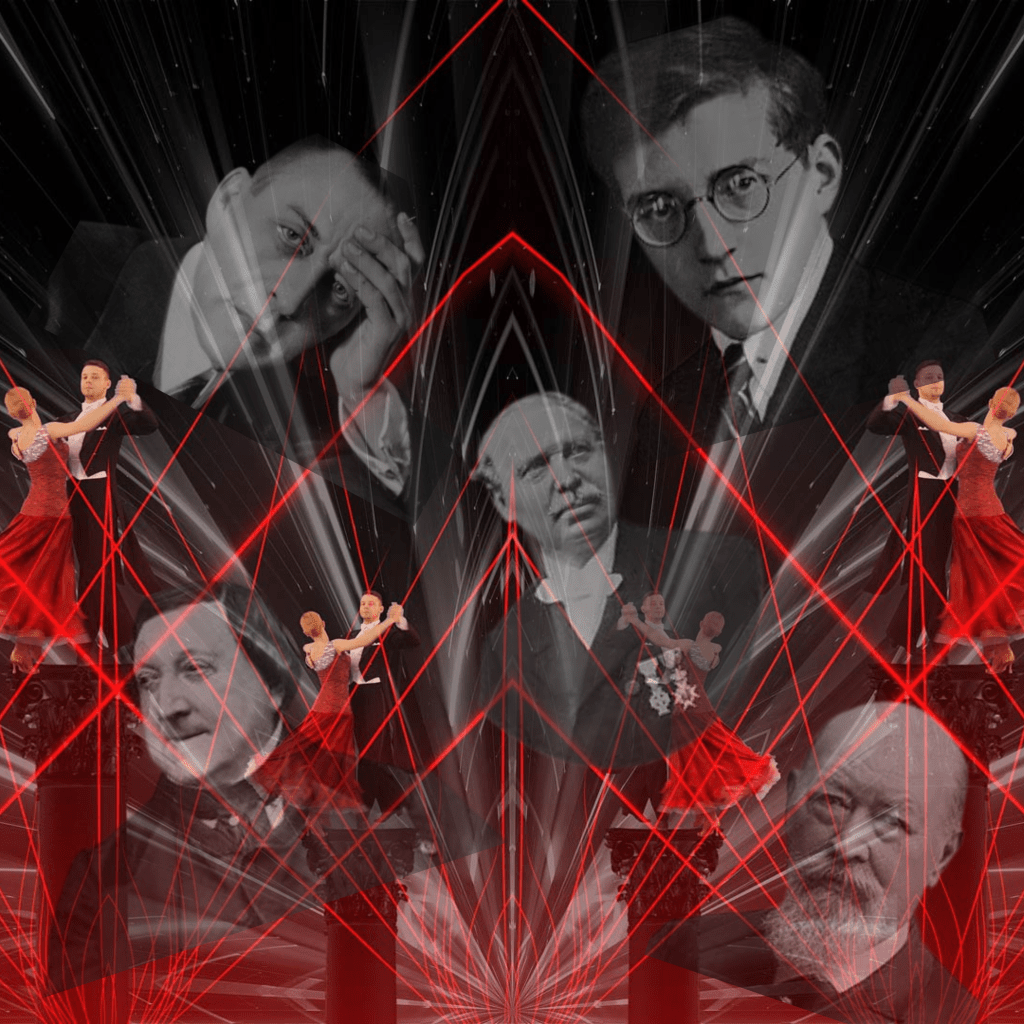

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Waltz No. 2 from Suite for Variety Orchestra, also known as Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 2 (1938)

Russian State Orchestra

Dmitri Yablonsky (conductor)

Franz von Suppé: (1819-1895)

Light Cavalry Overture (1866)

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Herbert von Karajan (conductor)

Hans Christian Lumbye (1810-1874)

Champagne Galop (1865)

Vienna Salon Orchestra

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943£

Italian Polka (1906)

Philharmonic Wind Orchestra

Marc Reift (conductor)

Gioccomo Rossini (1792-1868)

Overture to William Tell (1829)

National Orchestra of Santa Cecilia

Antonio Pappano (conductor)

Emmanuel Chabrier (1841-1894)

Fête polonaise from Le roi malgré lui (1887)

Emmanuel Chabrier (1841–1894), one of France’s most exuberant musical eccentrics, bridged the worlds of civil service and orchestral innovation with irrepressible panache. Born in Ambert, Auvergne, to a family of prosperous grocers, young Alexis-Emmanuel displayed prodigious talent on piano and composition. Yet practicality prevailed: at 18, he relocated to Paris, training in law and securing a post in the French Interior Ministry by 1861. There, amid bureaucratic drudgery, he immersed himself in the city’s bohemian arts scene, befriending poets like Verlaine and painters like Manet, while composing songs, piano pieces, and an unfinished opera. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 shattered his illusions of stability; stationed briefly in the National Guard, he emerged disillusioned, resigning his civil post in 1880 at age 39 to pursue music full-time.

Chabrier’s crowning theatrical achievement, the opéra comique Le roi malgré lui (The King in Spite of Himself), premiered on May 18, 1887, at the Théâtre Lyrique under the direction of Albert Carré. Librettist Emile de Najac and Paul Burani adapted a Mark Twain-inspired tale of a reluctant Polish king amid courtly intrigues, blending farce with Slavic exoticism. From Act II, Fête polonaise erupts as a standalone orchestral gem – a whirlwind polonaise evoking a grand Polish festival. Its propulsive rhythms, drawn from traditional mazurka and polonaise dances, surge with brassy fanfares, swirling woodwind flourishes, and string ostinatos that mimic whirling skirts and stamping boots. Scored for full orchestra, the piece builds from a majestic introduction to a riotous climax, its infectious vitality belying the opera’s modest initial reception (23 performances before closure amid financial woes). Chabrier, ever the bon vivant, infused it with his love of Wagnerian color—admired after ecstatic visits to Bayreuth – yet tempered by Gallic wit. The opera’s failure haunted him, exacerbating the melancholia that, coupled with syphilis, led to his death in 1894, but Fête polonaise endured, championed by conductors like Gabriel Pierné.

For a New Year’s Day concert, Fête polonaise dazzles as an uplifting interlude or finale. Its boisterous energy and celebratory pulse capture the thrill of revelry and renewal, echoing historical New Year balls where polonaises symbolised triumphant fresh starts, galvanising audiences to toast the year ahead.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Waltz No. 2 from Suite for Variety Orchestra

Dmitri Shostakovich, the Soviet Russia’s most paradoxical genius, navigated the treacherous currents of art and authoritarianism with symphonic depth and ironic wit. Born in St. Petersburg to a middle-class family, he entered the Petrograd Conservatory at 13, his prodigious talent blooming amid the 1917 Revolution’s chaos. His First Symphony (1926) catapulted him to fame, but Stalin’s regime soon demanded conformity. The 1936 Pravda denunciation of his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District as ‘muddle instead of music’ triggered a harrowing retraction, forcing Shostakovich into lighter genres for survival. Blockaded Leningrad in 1941-44 forged his defiant Seventh Symphony, yet perpetual scrutiny – exemplified by the 1948 Zhdanov Decree – compelled self-censorship. A party loyalist outwardly, his private anguish surfaced in coded dissidence, culminating in 15 string quartets of profound introspection. Shostakovich’s death in 1975 left a legacy of over 150 works, blending neoclassicism, jazz inflections, and existential dread.

Waltz No. 2, the gem of his Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 2 (1938), embodies this duality. Composed during a brief ‘thaw’ after his Pravda ordeal, the suite drew from revue and circus idioms, blending foxtrots, tangos, and waltzes with brash brass, sultry saxophones, and klezmer-esque clarinets. The original manuscript vanished in the 1941 Leningrad fire, presumed lost until its 1956 rediscovery and orchestration by Atovmyan. Renamed Suite for Variety Orchestra post-1948 (when jazz was ideologically suspect), Waltz No. 2 unfolds with beguiling nostalgia: a lilting 3/4 melody over a habanera bass, evoking faded ballrooms and fleeting elegance. Its bittersweet sheen – playful yet shadowed by minor-key undertones – hints at Shostakovich’s veiled critique of Soviet pomp, later amplified in films like The First Echelon (1956).

Waltz No. 2 appears here as a lyrical interlude, its characteristic blend of melancholy and charm reflecting both the festive and contemplative moods of the New Year. Scored for strings, woodwinds, and brass, it reveals Shostakovich’s gift for memorable melody and orchestral colour. Well known from his Suite for Variety Orchestra, the waltz has become one of the most recognisable pieces of 20th‑century dance music, performed worldwide as a symbol of elegance and nostalgia.

Franz von Suppé: (1819-1895)

Light Cavalry Overture (1866)

Franz von Suppé, the Viennese master of operetta, deftly bridged the effervescent style of Rossini with the buoyant waltzes of Johann Strauss II. Composing over 200 works that graced Europe’s stages during the rise of nationalism, Suppé was born in Spalato (now Split, Dalmatia) to a Belgian-Italian father and Neapolitan mother. Relocating to Vienna at age seven, he absorbed the influences of Haydn, Mozart, and Italian opera in the city’s theatres. After studies in law and singing at Padua, he embraced music full-time, making his conducting debut in Pressburg (now Bratislava) by 1840.

By 1845, Suppé led the Josephstadt and Leopoldstadt theatres in Vienna, where he crafted his operettas – lighthearted farces infused with patriotic undertones – to navigate the stringent censorship of the Metternich era. His breakthrough Poet and Peasant Overture (1846) fused march-like energy with lyrical tenderness, establishing a model for the galops and overtures that enlivened Vienna’s Kaffeehaus tradition. Suppé reached his pinnacle during the economic optimism of the 1860s Gründerzeit, rivaling Jacques Offenbach until Strauss Jr. surpassed him. Knighted ‘von Suppé’ in 1865, he premiered 30 operettas, pioneering the ‘overture potpourri’ that wove vocal themes into orchestral preludes. Afflicted by Bright’s disease, he passed away in Vienna, his funeral attended by 20,000 mourners – a fitting tribute to his enduring brilliance.

Light Cavalry Overture (1866) was composed as the overture to Suppé’s operetta Leichte Kavallerie, a vibrant work premiered on 21st May 1867 at Vienna’s Carltheater. The operetta recounts the adventures of a dashing hussar who reclaims his beloved amid Turkish intrigues. Written during Austria’s recovery from the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, the overture captures the thrill of mounted charges: a lively hornpipe introduction gives way to a spirited allegro, followed by trumpet fanfares and a tender violin trio conveying romance. The Overture outpaced the operetta’s more than 200 performances, becoming a perennial favourite in cartoons, galas, and concert halls. Ideal for a New Year’s Day programme, the Light Cavalry Overture serves as an exhilarating addition to the programme and resonates with Vienna’s tradition of performing thrilling overtures.

Hans Christian Lumbye (1810-1874)

Champagne Galop (1865)

Born on May 2, 1810, in Copenhagen, Hans Christian Lumbye emerged as Denmark’s preeminent composer of light music, often hailed as the ‘Chopin of the North’ for his masterful galops, waltzes, and polkas that captured the exuberant spirit of 19th-century Europe. The son of a military band flutist, Lumbye’s early life was steeped in music. At 14, he joined the Royal Artillery Regiment as a horn player, but his passion for composition soon led him to orchestrate dances for Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens, the city’s famed amusement park opened in 1843. Lumbye – appointed musical director from the outset – refined his style, blending Viennese-inspired dance rhythms such as polkas, waltzes, and gallops), with a Scandinavian lyricism, evoking the atmosphere of Copenhagen’s ballrooms and the revelry of an emerging leisure culture.

Lumbye’s Champagne Galop (1865) stands as a pinnacle of his oeuvre, premiered at Tivoli, this effervescent piece paints the imagery of clinking champagne glasses and merry toasts, its buoyant melody propelled by rapid galop rhythms popularised in Parisian salons. Scored for full orchestra, the work unfolds with an energetic allegro introduction building to a rollicking trio section, culminating in a coda that leaves audiences thrilled. Composed amid Denmark’s post-war recovery from the 1864 Schleswig-Holstein conflict, it offered escapist delight, reflecting Lumbye’s innate ability to transform everyday festivity into orchestral poetry. By his death in 1874, Lumbye had penned over 700 works, cementing his influence on composers like Johann Strauss II.

In a New Year’s Day concert, Champagne Galop shines. Its infectious energy and nod to champagne toasts perfectly mirrors the galop’s historical role in Viennese and Danish New Year galas.

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943£

Italian Polka (1906)

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873–1943) was born into a decaying aristocratic family on his estate near Novgorod. The youthful Sergei displayed prodigious gifts, entering the St. Petersburg Conservatory at nine and graduating from Moscow’s with gold medals in piano and composition. His Prelude in C-sharp minor (1892) and First Symphony (1897) heralded genius, but the symphony’s disastrous 1897 premiere – brutally mocked as a ‘cacophony’ – plunged him into depression. Hypnotherapy with Nikolai Dahl restored his confidence, yielding the Second Piano Concerto (1901), a global triumph that defined his lush, melancholic style blending Slavic soulfulness with Wagnerian heft.

The 1906 Italian Polka, originally a sparkling piano duet subtitled Polka de salon was composed for the wedding of Rachmaninov’s cousins Natalia and Arseny von Rindfleisch – friends from his Moscow days. Dedicated to the young couple, its effervescent rhythm evokes gaiety: while the humorous ‘oom-pah ’ bass-line adds jollity and sparkle. Privately premiered at family gatherings, it languished unpublished until 1918, and was later orchestrated by the composer and others (notably Victor Bendix in 1916) for salon orchestras. Its unpretentious charm offers a stark contrast to Rachmaninov’s brooding concertos, revealing his debt to salon traditions and Chopin-esque polish.

Exiled after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Rachmaninov settled in the U.S., touring relentlessly as a virtuoso while composing sparingly: the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini (1934) and Symphonic Dances (1940). His death in Beverly Hills marked a life of 750 concerts yearly in his final years, preserving Russian heritage abroad.

Italian Polka is ideal for a New Year’s Day concert, Its irrepressible rhythmic pulse echo polkas at Viennese New Year balls and offers a virtuosic toast to the new year ahead.

Gioccomo Rossini (1792-1868)

Overture to William Tell (1829)

Gioachino Rossini, Italy’s operatic luminary, transformed bel canto opera through his buoyant melodies and dramatic ingenuity, achieving both immense wealth and renown before his abrupt retirement at the age of 37. Born in Pesaro to musician parents – a horn-playing father and singer mother – he absorbed opera in Bologna’s theatres, debuting as a boy soprano and composing by 12. Entering Bologna’s Conservatorio at 18, Rossini churned out 39 operas in 20 years, from the farce La cambiale di matrimonio (1810) to masterpieces like The Barber of Seville (1816) and Semiramide (1823). His ‘Rossini crescendo’ – building orchestral swells to ecstatic peaks – captivated Europe; Napoleon dubbed him ‘Italy’s Mozart.’ By 1824, Paris’s Théâtre-Italien crowned him director, performing Le siège de Corinthe and Moïse. A 1829 move to the Opéra produced Guillaume Tell, his sole French grand opéra, before gastronomic exile in Bologna and Paris, where he hosted legendary feasts, composed witty sacred pieces, and quipped, ‘I compose to eat.’ Rossini’s death at 76 sealed his legacy as opera’s joyful colossus.

The Overture to William Tell (1829), crowning Rossini’s 40th opera, premiered triumphantly at Paris’s Salle Le Peletier on August 3, amid revolutionary fervor. Adapted from Schiller’s play of Swiss liberty against Habsburg tyranny, the opera follows archer Wilhelm Tell’s heroic defiance. The overture is well known for its iconic finale – a galloping presto featuring brass fanfares, thundering timpani, and string ostinatos depicting heroic flight. Scored for expanded orchestra, it fuses Rossini’s Italian verve with French grandeur, influenced by Méhul and Spontini. Though the opera received over 400 Paris performances and the overture became ubiquitous, fueling The Lone Ranger’s radio fame.

In a New Year’s Day concert, the William Tell Overture dazzles as a rousing opener or finale echoing European New Year traditions of performing triumphant overtures.

In Conclusion

It is a long-cherished tradition to greet the New Year through music – not only as an act of celebration, but also of reflection and renewal. Though the waltzes and polkas of the Strauss family have long defined this moment in time, this programme invites a broader perspective across Europe’s musical landscape, where composers of many nations captured the same festive spirit in their own distinctive voices. This ‘European’ New Year’s Day concert evokes the elegance of salons and ballrooms and the optimism that accompanies the turning of the year, reminding us that music’s capacity to uplift and unite transcends borders.

Leave a comment