The Bayreuth Festspielhaus stands as a monumental testament to Richard Wagner’s visionary genius, embodying his radical ideas on music drama and theatrical innovation. Conceived in the 1870s, this purpose-built opera house in Bavaria’s Bayreuth realised Wagner’s dream of a space dedicated to his monumental cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen, and mature operas. Unlike traditional theatres with proscenium arches and social distractions, it immerses audiences in the Gesamtkunstwerk – total artwork fusing music, drama, poetry, and visuals.

Wagner collaborated with architect Otto Brückwald to create a revolutionary venue on a wooded hilltop. The hidden orchestra pit, sunken and hooded, makes sound emerge invisibly, heightening mythic illusion. Double proscenium doors enable seamless scene changes, while steeply raked seating without boxes envelops every listener equally. Funded by global patrons like Ludwig II amid financial woes, it opened in 1876.

The Festspielhaus symbolised Wagner’s cultural revolution, rejecting 19th-century opera frivolity for profound spectacles from Norse sagas and Greek tragedy. Hosting annual festivals – interrupted only by wars – it became a Wagnerian pilgrimage. Its legacy influences modern stagecraft, from immersive audio to site-specific spaces, provoking ongoing debate on nationalism, anti-Semitism, and artistic transcendence under Wagner’s descendants.

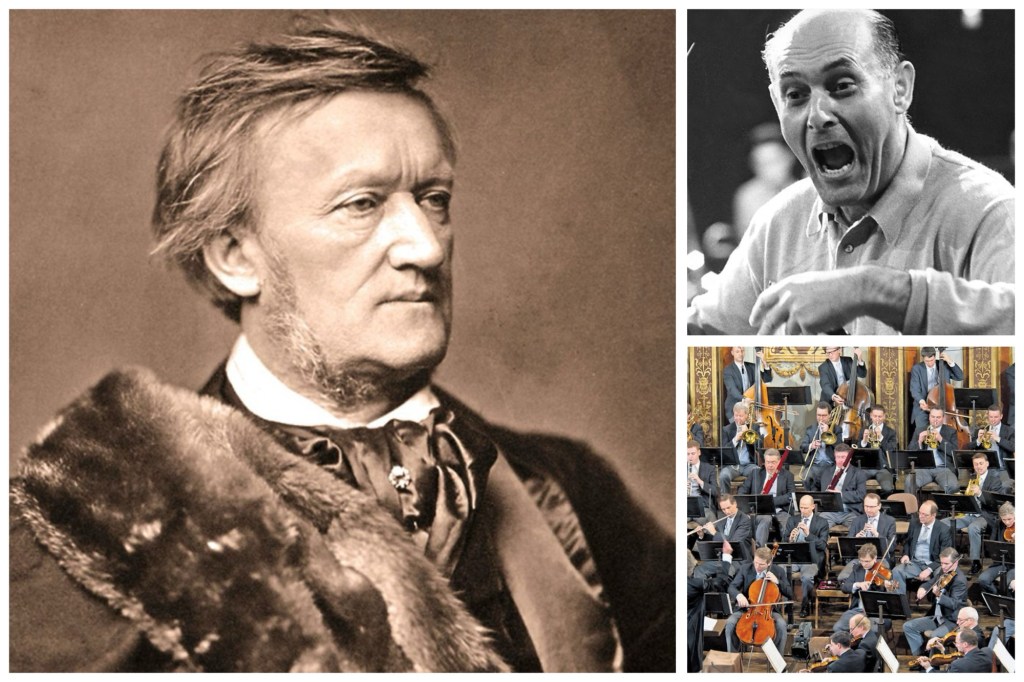

Richard Wagner

Overture to Tannhäuser

Vienna Philharmonic

Sir Georg Solti (conductor)

Richard Wagner

Siegfried Act 1

Nothung! Nothung! Neidliches Schwert

Placido Domingo

Orchestra of the Royal Opera

Antonio Pappano

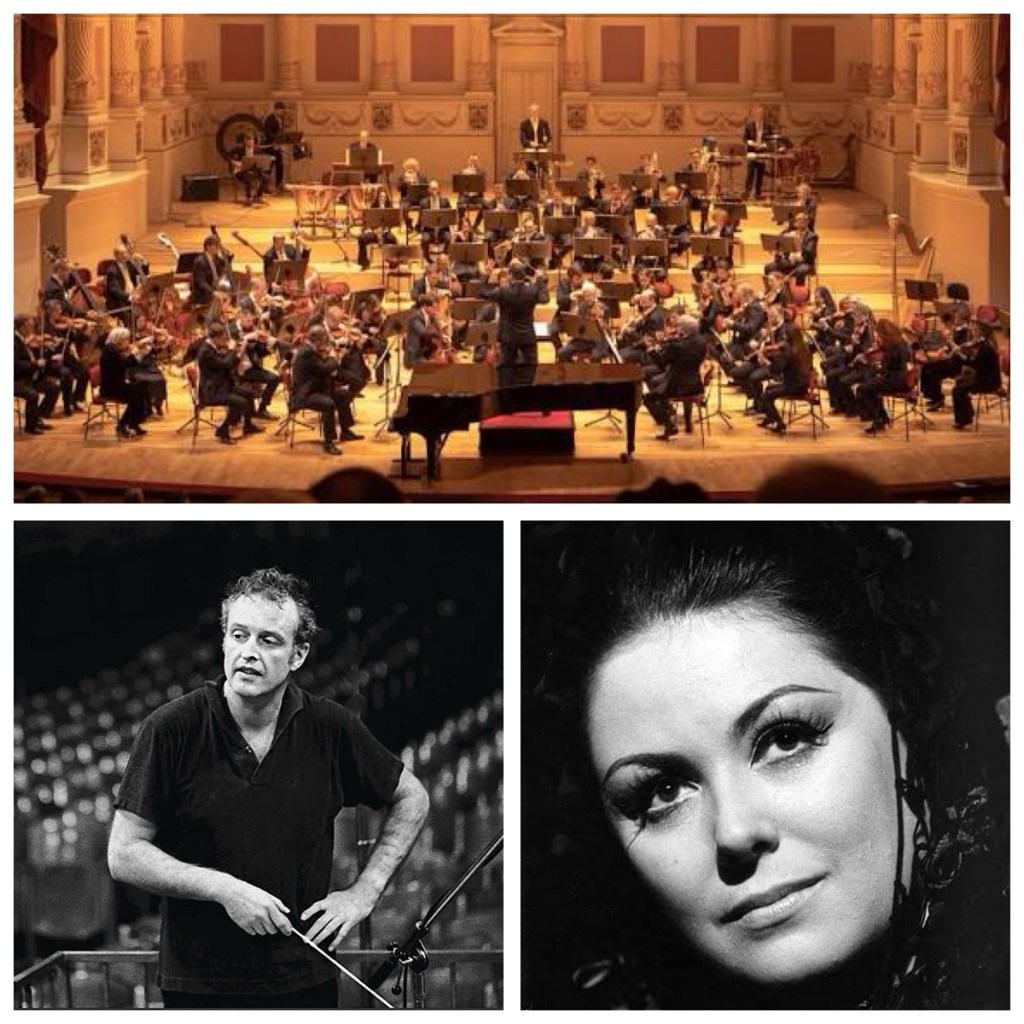

Richard Wagner

Tristan und Isolde

Liebestod (Love Death) Mild und leise wie er lächelt (Softly and gently, how he smiles)

Margaret Price (soprano)

Staatskapelle Dresden

Carlos Kleiber (conductor)

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Gotterdammerung

Siegfried’s Funeral March

Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus

Daniel Barenboim (conductor)

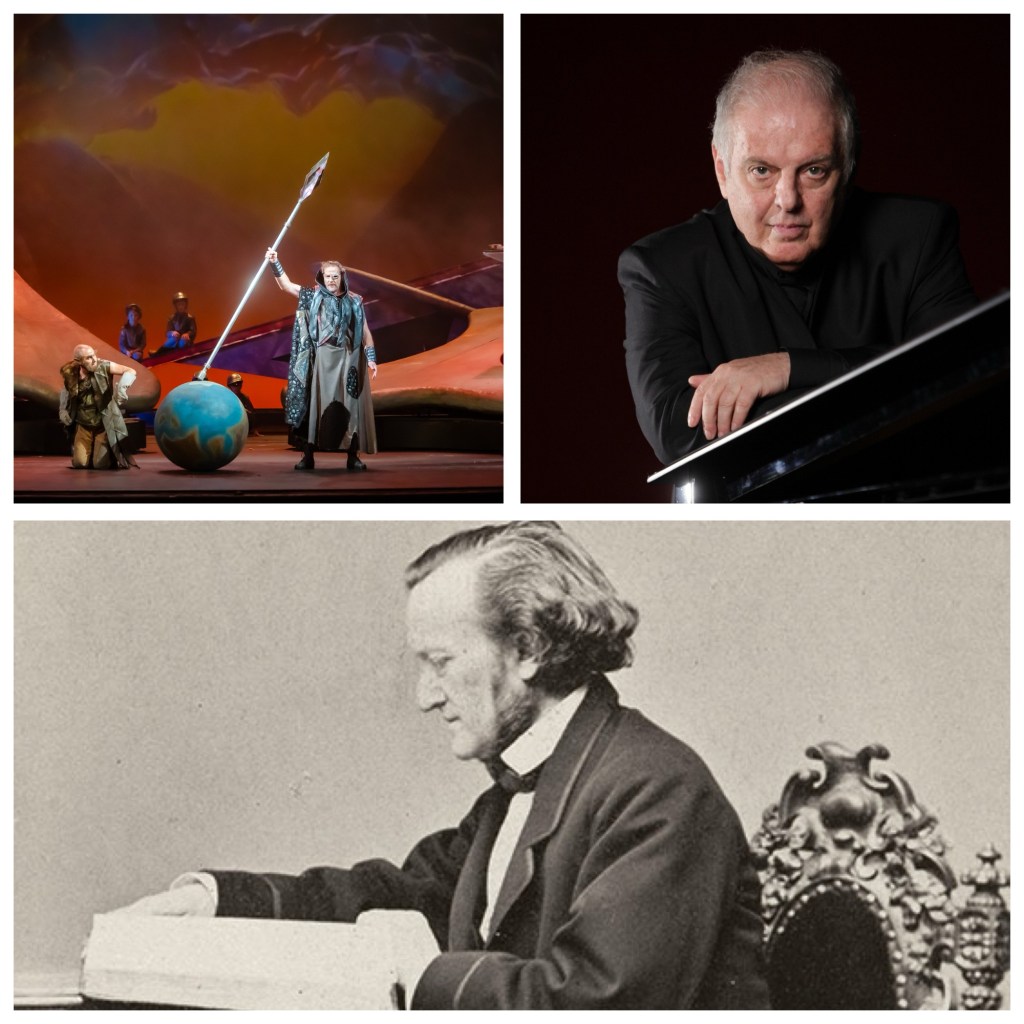

Richard Wagner

Ride of the Valkyries (1854)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Sir George Solti (conductor)

Richard Wagner

Overture to Tannhäuser

Richard Wagner’s Tannhäuser is a powerful meditation on the conflict between sacred and profane love, embodied in a story that fuses medieval legend with deeply personal reflection. Written in the mid‑1840s, the opera explores the spiritual journey of a poet torn between the sensual allure of Venus and the redemptive purity of Elisabeth. Through Tannhäuser’s inner turmoil, Wagner expresses a universal human struggle – the pull between passion and faith, desire and salvation.

The mythic framework draws on medieval German sources, combining tales of the minstrel‑knight Tannhäuser, the enchanted Venusberg, and the Wartburg Song Contest. Wagner transformed these into an allegory of sin, repentance, and artistic redemption, reflecting his own tension between social convention and creative freedom. The opera also marked a major step toward Wagner’s vision of the Gesamtkunstwerk — a ‘total work of art’ unifying music, poetry, and drama.

Musically, Tannhäuser contrasts two vivid sound worlds: the luxuriant harmonies of Venus’s realm, shimmering with chromatic intensity, and the radiant, hymn‑like sincerity of Elisabeth’s music. These opposing styles intertwine through Wagner’s inventive use of leitmotifs, anticipating the fully integrated musical language of his later masterpieces.

The world premiere took place at the Königliches Hoftheater in Dresden on 19 October 1845, with Wagner himself conducting. His niece, Johanna Wagner, created the role of Elisabeth, alongside Wilhelmine Schröder‑Devrient as Venus and Josef Tichatschek in the title role. Despite its ambition, the opera puzzled early audiences who found it emotionally and structurally unconventional.

Over the next decade, Wagner revised the score and drama, culminating in the 1861 Paris version, which featured a newly composed ballet and extended Venusberg scene. Its scandalous reception at the Paris Opéra only enhanced Wagner’s notoriety, but the work’s dramatic and spiritual power soon earned it lasting status in the repertory.

Today, Tannhäuser stands as a cornerstone of Wagner’s artistic evolution – a richly symbolic fusion of myth, philosophy, and human emotion that captures the timeless struggle between earthly passion and divine redemption.

Richard Wagner

Siegfried Act 1

Nothung! Nothung! Neidliches Schwert

Richard Wagner’s Siegfried, the third opera in his monumental Ring Cycle, tells a story of youthful strength, discovery, and destiny. The celebrated Nothung scene from Act I marks the moment when the young hero asserts his identity by forging the sword that will define his journey.

The act is set in a forest workshop, where the dwarf‑smith Mime struggles to reforge the broken sword Nothung, once wielded by Siegfried’s father, Siegmund. The sword symbolises courage, freedom, and moral strength. Though skilled in craft, Mime is too timid to restore it, for only one without fear can perform the task.

When Siegfried enters, he mocks Mime’s failed efforts and the useless shards of metal. Bold and impulsive, he resolves to attempt the work himself. As the forge glows, Wagner’s music builds with vivid rhythmic force, echoing the clang of hammer and anvil. Siegfried’s cry Nothung! Nothung! Neidliches Schwert! (Nothung! Nothung! Enviable sword!) resounds as the blade is reborn from the fire. In triumph, he shatters the anvil with a single blow, proving both his strength and his destiny.

This moment symbolises Siegfried’s coming of age. The forging of the sword mirrors his forging of identity – fearless, independent, and guided by instinct rather than deceit. Yet Mime’s envy soon turns to treachery: he plans to poison Siegfried after the hero slays the dragon Fafner and wins the cursed Ring of power.

Wagner composed Siegfried between 1856 and 1871, pausing midway to write Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger. Its exuberant first act reflects his renewed optimism and belief in creative rebirth. The forging of Nothung can also be heard as an allegory for the artist’s courage – a moment when creation becomes liberation.

Siegfried received its world premiere on 16 August 1876 at the Bayreuth Festival Theatre under Wagner’s direction, as part of the first complete performance of the Ring Cycle.

Richard Wagner

Tristan und Isolde

Liebestod (Love Death) Mild und leise wie er lächelt (Softly and gently, how he smiles)

The Liebestod, or Love‑Death, forms the luminous conclusion to Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. In Act III, Isolde stands beside the lifeless body of Tristan, not in despair but in rapture. Beginning with the words Mild und leise wie er lächelt (Softly and gently how he smiles) she imagines him awakening into radiant peace, freed from earthly suffering and united with her in an eternal realm of love.

Wagner’s music carries this transformation with extraordinary power. Its chromatic harmony and fluid orchestration blur the boundary between longing and fulfilment, life and death. The melody rises and falls in slow surges, mirroring Isolde’s ecstatic vision as passion dissolves into serenity. The climax, radiant rather than tragic, culminates in her transfiguration – the moment when love transcends mortality.

Although Liebestod has become the widely known title, Wagner himself called this ending Isoldes Verklärung (Isolde’s Transfiguration) highlighting its spiritual essence rather than its tragedy. The word Liebestod (Love‑Death) gained currency through Franz Liszt, who prepared a piano and orchestral arrangement before the opera’s premiere, helping to popularise the work.

Philosophically, the scene reflects Wagner’s deep engagement with Arthur Schopenhauer’s ideas – that death releases the soul from desire, allowing unity with the infinite. Isolde’s final vision thus becomes a philosophical and emotional liberation, the merging of love, spirit, and timeless stillness.

Composed between 1857 and 1859, Tristan und Isolde marks a turning‑point in Western music. Its daring harmonic language and emotional depth profoundly influenced composers from Mahler and Strauss to Debussy and Schoenberg. The opera received its world premiere in Munich on 10 June 1865, conducted by Hans von Bülow.

In concert, the Liebestod is often performed on its own, or paired with the opera’s Prelude to form a complete musical arc – from restless longing to radiant release. Combining poetry, orchestral colour, and spiritual intensity, this closing scene captures the essence of Wagner’s mature style: music that transforms passion into transcendence, where love and death become one

Richard Wagner

Gotterdammerung

Siegfried’s Funeral March

Siegfried’s Funeral March is one of the most powerful orchestral moments in Richard Wagner’s monumental Ring Cycle. It appears in Act III of Götterdämmerung, the final drama of the four‑opera saga, immediately after the hero Siegfried is treacherously murdered by Hagen. As his body is laid upon his shield and borne away by his companions, the music narrates his life and fate through a web of soaring orchestral themes.

The Ring Cycle, composed between 1848 and 1874, tells a mythic story of gods, heroes, and the cursed Ring of power that ultimately brings about the twilight of the gods. The Funeral March marks the turning point where its greatest hero falls, and his death begins the chain of events that will end the old world order.

A solemn timpani roll begins the music, sounding like a distant death knell. Out of this emerge fragments of Siegfried’s Valiant and Sword motifs, memories of his fearless youth and the forging of Nothung. Shapes of Brünnhilde’s love theme recall tenderness and devotion, while darker strains suggest the Curse of the Ring that has haunted every generation of characters. By interweaving these leitmotifs, Wagner transforms the march into a wordless retelling of Siegfried’s journey – from innocent strength and joy to betrayal and death.

The orchestration is vast, featuring extended brass (including Wagner tubas), woodwind, harps, percussion, and strings, creating sonorities at once noble and tragic. The shifting harmonies evoke grief, rage, and reverence – portraying not only Siegfried’s fall but the mourning of a whole mythic world.

Composed between 1869 and 1874, Götterdämmerung brought Wagner’s 26‑year epic project to completion. The Ring’s first full performance took place in Bayreuth in August 1876, conducted by Wagner himself. The Funeral March quickly gained an independent life in the concert hall, its grandeur and emotional depth making it one of the defining orchestral excerpts of nineteenth‑century music – a monumental farewell to the hero and a prelude to the twilight of the gods.

Richard Wagner

Ride of the Valkyries (1854)

Ride of the Valkyries is one of the most thrilling and recognisable moments in all nineteenth‑century music. It opens Act III of Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), the second opera in Wagner’s epic four‑part cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung).

Composed between 1851 and 1856, with the main draft completed in 1854, the piece was fully orchestrated by 1856. The music depicts the dramatic arrival of the Valkyries – the eight warrior daughters of Wotan, king of the gods – as they gallop across the sky to collect fallen heroes from the battlefield and carry them to Valhalla. Wagner paints this mythic scene through surging orchestral motion, bold brass fanfares, and galloping rhythms that vividly evoke the flight of celestial horsewomen.

The act begins with the famous ‘Ride’ theme in sweeping triplet patterns for the strings, answered by powerful brass calls. As the curtain rises, the Valkyries’ jubilant cries sound above the orchestra, their shouts of greeting intertwining with the music’s relentless energy. The combination of heroic excitement and raw vocal power makes this one of the most exhilarating scenes in the entire Ring Cycle.

Although Wagner initially refused to allow the ‘Ride’ to be performed separately – he called it ‘an utter indiscretion’ when taken out of context – audiences were so drawn to its vitality that he eventually relented after the Ring’s first complete performances at Bayreuth in 1876. Since then, it has become an independent concert favourite and one of Wagner’s most frequently performed excerpts, lasting about eight minutes in orchestral form.

Historically, Die Walküre was written during Wagner’s years of political exile. He worked on much of the Ring Cycle while in Switzerland, developing his revolutionary ideas about music drama during the 1850s. The Ride of the Valkyries captures that creative daring – music that unites myth, drama, and orchestral brilliance into a single sweeping vision.

Today, this thrilling piece remains a symbol of Wagner’s power to turn legend into sound — an immortal portrayal of strength, courage, and unstoppable motion.

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus and Wagner’s Legacy

The Festspielhaus opened in 1876 with the first complete performance of Der Ring des Nibelungen. The audience included Emperor Wilhelm I, Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil, Friedrich Nietzsche, and many of Europe’s leading artists. Though the early festivals were artistically triumphant and financially shaky, Bayreuth soon became – and remains – a sacred site for Wagner’s music.

After Wagner’s death, the theatre stayed under family control. His son Siegfried, then grandsons Wieland and Wolfgang, carried on the tradition. Under their leadership, Bayreuth evolved from rigid preservation of Richard’s stage directions to bold reinterpretations that reflected modern theatre practice. The festival also confronted darker chapters – its association with Winifred Wagner and Nazi patronage in the 1930s – and has since openly acknowledged and repudiated that history.

Today, under the direction of Katharina Wagner, the composer’s great‑granddaughter, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus continues as a centre of innovation and debate – a place where Wagner’s music, with all its passion, vision, and controversy, is re‑examined for each new generation. It remains a powerful symbol of artistic ambition: the theatre where sound, myth, and humanity merge in Wagner’s enduring quest for the ideal art form.

Leave a comment