Polish music has long carried the echoes of its nation’s turbulent history – a story marked by loss, resilience, and renewal. Following the late‑18th‑century partitions, Poland disappeared from the map of Europe, its people living under foreign rule. When political freedom was suppressed, art became a sheltered space for national memory. Music, in particular, offered a voice through which Poles could affirm their identity, pride, and spirit.

In 19th‑century Europe, the movement of musical nationalism sought to celebrate native traditions and local colour. In Poland, this took on a deeply emotional character. Living in exile, Frédéric Chopin transformed Polish dance rhythms into poetry for the piano. His mazurkas and polonaises blended classical elegance with rustic vitality, expressing a quiet but unmistakable patriotism. Their impact endured far beyond their salon origins – so powerfully, in fact, that the Nazis later banned Chopin’s music in occupied Poland for its patriotic symbolism.

Other composers continued this cultural mission. Stanisław Moniuszko drew on folk melody and stories of rural life to create operas that nurtured a shared national feeling, while Ignacy Paderewski combined international fame with activism, composing music that inspired unity and advocating for Polish independence abroad.

After 1918, when independence was regained, Karol Szymanowski redefined what Polishness could mean in the modern age. Drawing inspiration from the folk traditions of the Tatra mountains, he fused modern harmony with local colour to express a forward‑looking sense of identity.

Through these composers, Poland’s voice was never silenced. Their music – drawn from the homeland – demonstrates how cultural nationalism could endure and flourish even when political expression was denied, sustaining the nation’s soul through beauty, memory, and sound.

Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849)

Mazurka Op. 6, No. 1 in F-sharp minor.

Arthur Rubinstein (piano)

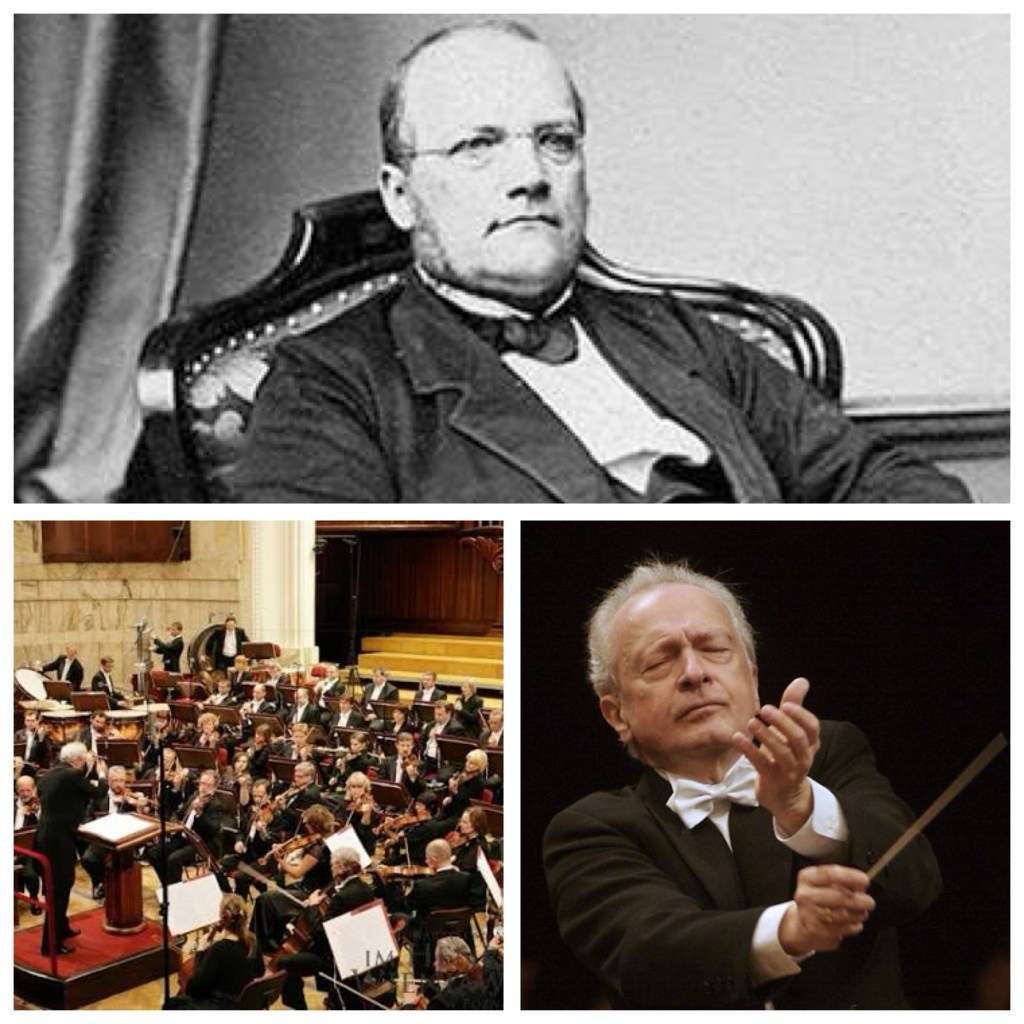

Stanisław Moniuszko (1819–1872)

Halka Overture

Warsaw Philharmonic Orchedtra

Antoni Wit (conductor)

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860–1941)

Overture in E‑flat minor

Polish National Symphony Orchestra

Antoni Wit (conductor)

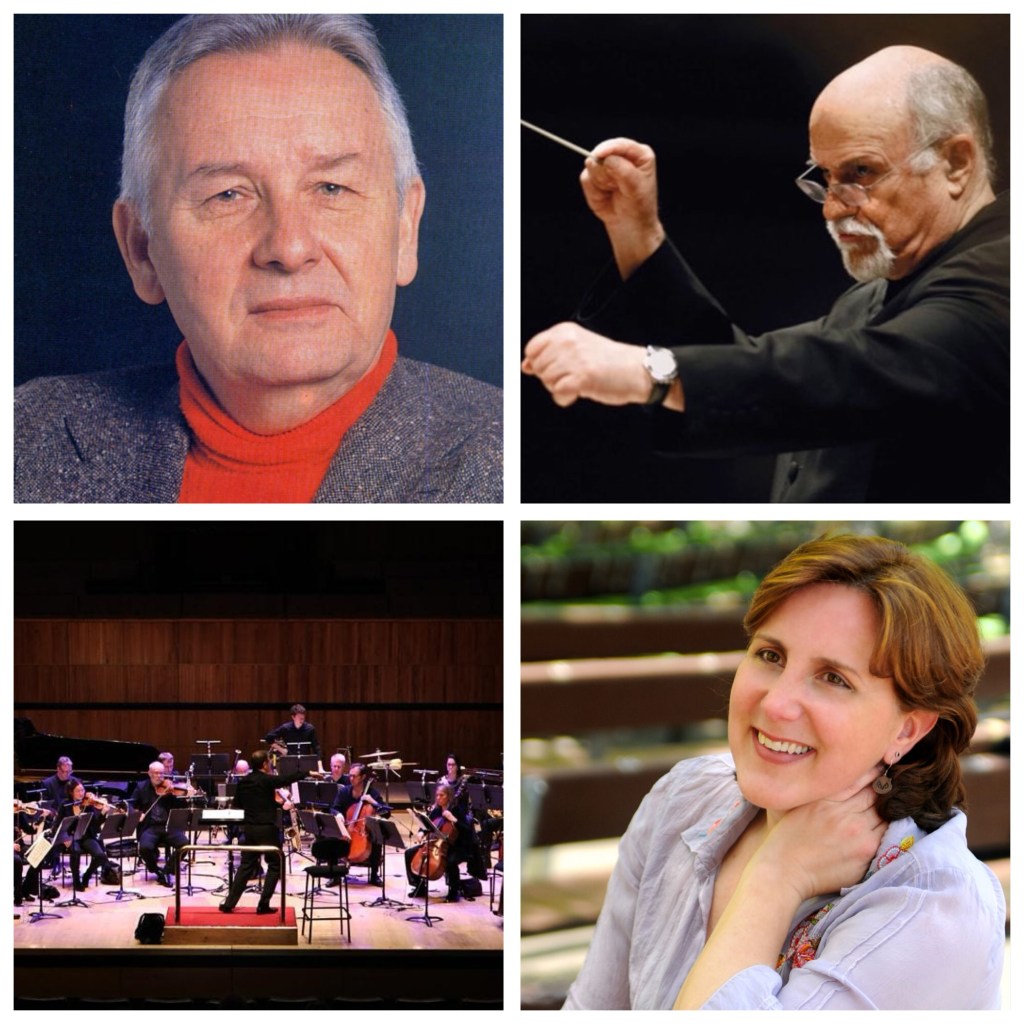

Henryk Górecki (1933–2010)

Symphony No. 3 Symphony of Sorrowful Songs

Dawn Upshaw (soprano)

London Sinfonietta

David Zinman (conductor)

Witold Lutosławski (1913–1994)

Concerto for Orchestra (1954)

Cleveland Orchestra

Christoph von Dohnanyi (conductor)

Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849)

Mazurka Op. 6, No. 1 in F-sharp minor

Chopin composed his first set of mazurkas in 1830-31, during one of the most turbulent periods in Poland’s history. The November Uprising against Russian rule erupted just as he was leaving Warsaw for Vienna, an exile from which he would never return. The Mazurka in F‑sharp minor, his Op. 6 No. 1, captures both the vitality of Polish folk tradition and the young composer’s deepening sense of homesickness and national pride.

While rooted in the rhythms of the rural mazurka dance – marked by lilting accents, modal harmonies, and sudden shifts in mood – Chopin’s version was intended for the salon rather than the village floor. He elevated the folk idiom into a poetic piano language that expressed the heart of Polish identity. The piece’s wistful lyricism and rhythmic elasticity evoke both the dance’s rustic origins and a more personal nostalgia for the homeland.

Composed on the eve of exile, this mazurka became emblematic of Chopin’s lifelong attachment to Poland. In Parisian salons, such works resonated far beyond their intimate scale, allowing European audiences to glimpse the spirit of a nation denied independence.

Critics like Robert Schumann recognised in these pieces a unique national authenticity – a voice that spoke both of Poland’s folk roots and its cultural struggle. Chopin’s mazurkas, performed by exiles and admired by audiences across Europe, stood as subtle but enduring affirmations of Polish identity. Through music, Chopin transformed his private longing into a universal symbol of resilience and belonging.

Stanisław Moniuszko (1819–1872)

Halka Overture

Warsaw Philharmonic Orchedtra

Antoni Wit (conductor)

Known as the father of Polish national opera, Stanisław Moniuszko gave musical voice to the Polish nation during the 19th century, when the country was partitioned and under foreign rule. His operas and songs transformed folk traditions into powerful cultural symbols, expressing unity and resilience at a time when political freedom was denied.

Born in 1819 near Minsk (now in Belarus) into a Polish landowning family, Moniuszko studied in Warsaw and Berlin under Carl Friedrich Rungenhagen before settling in Vilnius as an organist and teacher. There he began composing songs steeped in Polish folklore and poetry, later published in his influential collection Śpiewnik domowy (Songbook for Home Use). His ambition to create a truly national opera culminated in Halka, composed between 1846 and 1847.

The original two‑act version of Halka was first performed in concert in Vilnius in 1848 and staged there in 1854 to mixed reviews. Moniuszko then expanded the work to four acts, adding vivid dance episodes and new vocal scenes. Its Warsaw premiere on 1st January 1858 at the Teatr Wielki was a triumph, hailed as the birth of Polish national opera. Incorporating traditional dance rhythms – the mazurka, polonaise, kujawiak, and krakowiak – and a story of a peasant girl betrayed by a nobleman, Halka became an allegory for the injustices of partition‑era Poland.

The opera’s success established Moniuszko as a central figure in Polish cultural life. His later works, including The Haunted Manor (Straszny Dwór, 1865), were celebrated for their nationalist spirit; TheHaunted Manor was even banned by Russian authorities for its patriotic themes.

When Moniuszko died in 1872, his Warsaw funeral drew thousands in a patriotic demonstration of mourning and gratitude. His music – blending folk rhythms, lyrical invention, and national feeling – remains a cornerstone of 19th‑century Polish identity and opera.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860–1941)

Overture in E‑flat minor

Ignacy Jan Paderewski was one of the most remarkable figures in Polish cultural and political life – a virtuoso pianist, composer, statesman, and humanitarian whose art and patriotism were inseparable. Living during a time when Poland remained partitioned, he believed music carried a national duty: to preserve and celebrate the spirit of a nation without a state.

Born near Tarnopol (now in Ukraine) in 1860, Paderewski rose to international fame as a pianist renowned for his poetic touch and charisma. As a composer, he sought to weave Polish elements into Romantic forms, producing works such as the Symphony Polonia, the Polish Phantasy Op. 19, and the infectious Polish Dances Ops. 5 and 9 .

His Overture in E‑flat minor, written in Berlin between March and July 1884 while studying with Heinrich Urban, was his first large‑scale orchestral composition. Lasting around ten minutes, it blends the lyricism of late Romanticism with rhythmic and melodic inflections that hint at Polish dance idioms. Though unpublished during his lifetime, the work was later included in Paderewski’s Complete Works and stands as an early sign of his emerging national voice.

During the First World War, Paderewski used his fame to unite Polish communities abroad and raise support for independence, combining concert performances with impassioned speeches. Following the war, he served briefly as Poland’s first Prime Minister and Foreign Minister in 1919, playing a key role in securing international recognition of the newly independent state.

Even after retiring from politics, Paderewski remained Poland’s cultural ambassador. His life and music continue to embody the country’s artistic brilliance and unyielding national spirit.

Henryk Górecki (1933–2010)

Symphony No. 3 Symphony of Sorrowful Songs

Few works of the late twentieth century have spoken to listeners with such emotional directness as Henryk Górecki’s Symphony No. 3, known as the ‘Symphony of Sorrowful Songs’. Composed in 1976, it is scored for soprano and orchestra and unfolds over three slow, meditative movements. Each movement sets a Polish text reflecting grief, motherhood, and spiritual endurance – themes deeply rooted in Poland’s experience of suffering and survival.

The first movement draws on a fifteenth‑century lament of the Virgin Mary mourning her crucified son. The second sets words inscribed by an eighteen‑year‑old girl on the wall of a Gestapo cell in Zakopane during the Second World War: a prayer to her mother expressing both fear and faith. The third movement quotes a Silesian folk song in which a mother laments the loss of her son in war. Together, these texts weave a timeless meditation on human pain and love, with echoes of Poland’s long struggle for national and spiritual identity.

Born in Czernica, Silesia, Górecki studied in Katowice and emerged in the 1950s as a leading figure of the Polish avant‑garde, influenced by Webern and Stockhausen. By the mid‑1970s, he had turned away from complex modernism toward a simpler and more spiritual style, fusing modal harmony, folk inflections, and a sense of sacred chant.

The symphony achieved unexpected worldwide fame through the 1992 recording by Dawn Upshaw and David Zinman with the London Sinfonietta, which sold more than a million copies. This success brought Górecki international recognition and positioned him as a central musical voice of Poland’s cultural renewal after decades of political oppression.

Górecki’s Symphony No. 3 endures as both a personal expression of faith and a collective testament to Poland’s resilience, sorrow, and hope.

Witold Lutosławski (1913–1994)

Concerto for Orchestra (1954)

Witold Lutosławski’s Concerto for Orchestra marks a turning point in post‑war Polish music and in his own creative development. Written between 1950 and 1954 on commission from Witold Rowicki, artistic director of the Warsaw Philharmonic, it was premiered in 1954 by the newly re‑formed National Philharmonic Orchestra. The work immediately established Lutosławski as the leading Polish composer of his generation, balancing accessible national elements with modern musical sophistication.

Drawing on Polish folk melodies – especially from the Kurpie and Mazowsze regions – the Concerto transforms these sources through inventive orchestration and bold harmonic language. Rather than quoting folk tunes literally, Lutosławski re‑imagined them with contrapuntal density and rhythmic vitality, fusing folk roots with neo‑classical craftsmanship and touches of modernist dissonance. The three‑movement structure (Intrada, Capriccio notturno e Arioso, and Passacaglia, Toccata e Corale) recalls the Baroque concerto tradition while creating a continuous symphonic arc.

Composed during a period when artists in Poland were pressured to conform to the ideals of Socialist Realism, the Concerto for Orchestra successfully satisfied official taste while preserving artistic depth. Its energetic rhythms, folkloric character, and large orchestral sonorities aligned with state expectations, yet its sophistication and emotional integrity quietly affirmed the independence of Polish art.

Born in Warsaw in 1913, Lutosławski studied both mathematics and music there. During the Nazi occupation he performed piano duos in clandestine concerts to preserve Polish culture. His early works were neoclassical in spirit, though his Symphony No. 1 was banned in 1949 as ‘formalist’. After the Concerto, he moved steadily toward new techniques – serialism, atonality, and later his distinctive ‘controlled aleatory’ style – creating a language that influenced composers worldwide.

Recognized internationally and awarded Poland’s Order of the White Eagle, Lutosławski remains one of the most original voices of 20th‑century music. His Concerto for Orchestra bridges tradition and innovation, embodying both Poland’s cultural heritage and the resilient modernism of its post‑war spirit.

In Conclusion

Throughout Poland’s turbulent history – partitioned, occupied, and reborn – music has served as a language through which the nation has spoken when speech itself was suppressed. From Chopin’s poetic evocations of a lost homeland to Moniuszko’s operatic portraits of everyday Polish life, from Paderewski’s dual identity as virtuoso and statesman to the moral and spiritual resonance found in the twentieth-century works of Lutosławski and Górecki, each generation of composers has transformed adversity into music.

Their work stands not merely as art but as witness – an archive of resilience, faith, and shared memory. Through their distinct voices, these creators sustained a dialogue across time, affirming that Poland’s essence could be neither erased nor silenced. Even as the political landscape shifted, the sounds of their work continued to shape the national consciousness, expressing grief without despair and pride without arrogance.

In the Poland of today – free, forward-looking, and deeply aware of its past – their legacy endures. The lives of Chopin, Moniuszko, Paderewski, Lutosławski, and Górecki remind us that music is not merely an accompaniment to freedom but one of its most profound expressions. As long as their works are played and cherished, the ideal they embodied – a nation expressing its soul through sound – remains vibrantly alive.

Leave a comment