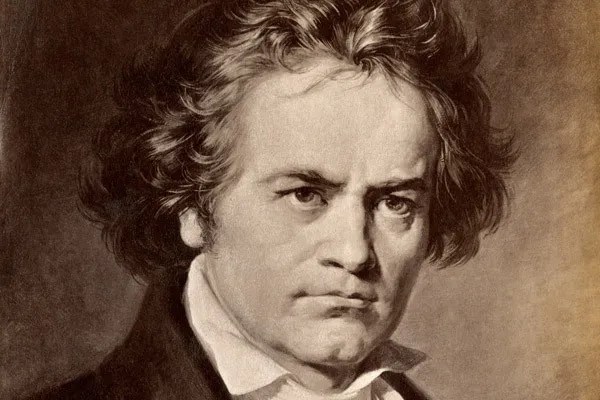

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) was born in Bonn but spent most of his adult life in Vienna, where he became a key figure in the shift from the Classical era of Haydn and Mozart to the Romantic age. He arrived in Vienna in 1792 to study with Haydn and quickly gained fame as a passionate virtuoso pianist and a fiercely independent composer who sought to live by his art rather than serve a court or patron.

In the 1790s, Vienna was a lively musical centre with an active culture of home music-making. Publishers sought dances, piano pieces, and chamber works to satisfy the tastes of amateur musicians. Beethoven’s early Viennese works – piano sonatas, orchestral pieces, and sets of German dances – show him mastering traditional Classical style while already revealing his bold personality through rhythmic energy and a strong sense of character. Even in his lighter compositions, his clarity of texture and individuality set him apart from many of his contemporaries.

By the early 1800s, Beethoven had established himself not only as a brilliant performer but as an original and profound composer. He absorbed the influence of Haydn and Mozart yet expanded and deepened forms such as the sonata, string quartet, and symphony. Both his famous and lesser-known works demonstrate his drive for contrast, drama, and expressive intensity.

As his deafness worsened in the 1810s and 1820s, Beethoven withdrew from public life and turned inward. His late works are concentrated, complex, and spiritually searching, rich in contrapuntal writing and emotional depth. Beethoven came to embody the Romantic vision of the artist as a visionary figure, confronting personal struggle and expressing universal emotion through music. Across his entire output, one hears his integrity, humanity, and unmistakable voice.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

German Dances, WoO 8 No 12 (1795)

Academy of St Martin’s in the Fields

Sir Neville Marriner (conductor)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Piano Sonata No. 19 in G Minor, Op. 49, No. 1 (1795 to 1797)

Daniel Barenboim (piano)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Cantata on the Death of Emperor Joseph II (1790):

San Francisco Symphony Orchestra

Michael Tilson Thomas (conductor)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Auld Lang Syne (1817-1818)

Felicity Lott, Elizabeth Leyton, Ursula Smith, John Mark Ainsley, Thomas Allen

Malcolm Martineau (piano)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

The Consecration of the House Op 124

Orchestre Lamareux

Igor Markevitch (conductor)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

German Dances, WoO 8 No 12 (1795)

Composed in 1795, Beethoven’s Twelve German Dances belong to the composer’s early Viennese years, a time when he was quickly gaining fame as both a virtuoso pianist and an emerging symphonic voice. Written for orchestra, the dances were first performed at a masked ball held on 22 November 1795 to raise funds for the Society of Fine Artists’ pension fund — a typical social and charitable occasion in late 18th‑century Vienna.

In these pieces, Beethoven followed the tradition of light, elegant dance sets written for public entertainment, yet he infused them with his own lively imagination and orchestral flair. The German dance was a popular ballroom form related to the waltz, usually in triple time and characterised by rhythmic vitality and charm. Beethoven enriches this simple structure with playful surprises, dynamic contrasts, and colourful instrumentation.

The orchestration reveals his early inventiveness: bright woodwinds, resonant brass, and even piccolo and ‘Turkish’ percussion — bass drum, cymbals, and triangle — add sparkle and exotic colour, reflecting the fashionable Ottoman style of the time. Each short dance has its own character, from rustic energy to courtly grace, and together they form a vivid sequence of moods.

The twelfth and final dance in C major provides a thrilling conclusion. Its spirited rhythms, trumpet fanfares, and festive coda — almost twice as long as the other dances — bring the set to an exuberant close.

Though intended as social music, the German Dances, WoO 8 also hint at Beethoven’s developing orchestral voice: his gift for vivid contrast, rhythmic drive, and the transformation of simple dance tunes into something more expressive and symphonic.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Piano Sonata No. 19 in G Minor, Op. 49, No. 1 (1795 to 1797)

Composed in Beethoven’s mid-twenties, the Piano Sonata No. 19 in G minor belongs to his early period, when he was establishing himself in Vienna as both virtuoso pianist and composer. Although probably written between 1795 and 1797, the sonata was published only in 1805 by Beethoven’s brother, who saw its value despite the composer’s modest view of the piece.

Unlike his grander, more technically demanding later sonatas, this work is relatively short and approachable, radiating clarity and charm. It stands out as Beethoven’s only piano sonata in G minor — a key often associated with drama and pathos, yet here treated with restraint and poetic balance. The music combines Classical grace with hints of the deeper emotional expression that would soon define Beethoven’s mature style.

The sonata unfolds in just two movements, an unusual structure for Beethoven. The opening Andante in G minor sings with lyrical melancholy, coloured by graceful phrasing and delicate shading. The second movement, a playful Rondo in G major, provides a bright counterbalance — full of light, wit, and gentle humour.

Together, these contrasting movements reflect both sides of the young Beethoven: the introspective poet and the spirited innovator, looking beyond Classical convention toward a more personal musical language.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Cantata on the Death of Emperor Joseph II (1790)

Beethoven composed this early cantata at just nineteen, while still living in his native Bonn. Written in 1790 to commemorate the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, it was intended for a local memorial service but was never performed during the composer’s lifetime. The ambitious scale and musical complexity proved beyond the means of the city’s musicians, leaving the work unplayed until its posthumous premiere in Vienna in 1884 – fifty‑seven years after Beethoven’s death.

Set to a German text lamenting the emperor’s passing and celebrating his enlightened ideals, the Cantata on the Death of Emperor Joseph II reveals the young Beethoven’s dramatic flair and deep sense of expression. Cast in seven movements, it combines solemn choruses and intense solo writing in ways that foreshadow his later masterpieces. In fact, several musical ideas from the cantata make reappearances in his opera Fidelio, written about fifteen years later.

Although overshadowed by the mature symphonies and piano works, this cantata offers a fascinating glimpse of Beethoven at the threshold of greatness—already capable of marrying nobility of spirit with emotional power.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Auld Lang Syne (1817-1818)

During his years in Vienna, Beethoven did not only write symphonies, concertos, and sonatas; he also turned to the world of folk song. In the later 1810s he received a commission from the Edinburgh publisher and song collector George Thomson, who invited leading composers to arrange traditional Scottish melodies for the flourishing market of domestic music-making. Among the songs Beethoven worked on was the now world‑famous Auld Lang Syne, issued as No. 11 in his collection 12 Scottish Songs, WoO 156, composed around 1817–1818 and published in 1818.

Thomson specifically asked Beethoven to keep his accompaniments straightforward, so that amateur singers and pianists could perform these songs at home without difficulty. Beethoven largely respected this brief, providing textures that are clear, singable, and gratifying to play, while still adding subtle harmonic touches and tasteful inner voices that reveal the hand of a great composer. The arrangement preserves the lively, dance‑like character associated with the tune’s Scottish origins, even as it situates the melody within a refined Viennese drawing‑room style.

These folk‑song settings illuminate a different side of Beethoven: the practical craftsman and musical humanist, interested in bridging high art and everyday music-making. In Auld Lang Syne the simplicity of the accompaniment allows the well‑known melody and text to speak directly, whether in solo or ensemble performance. Beethoven’s version connects the intimate, sociable world of nineteenth‑century parlour song with the enduring tradition of singing Auld Lang Syne to mark endings, farewells, and new beginnings.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

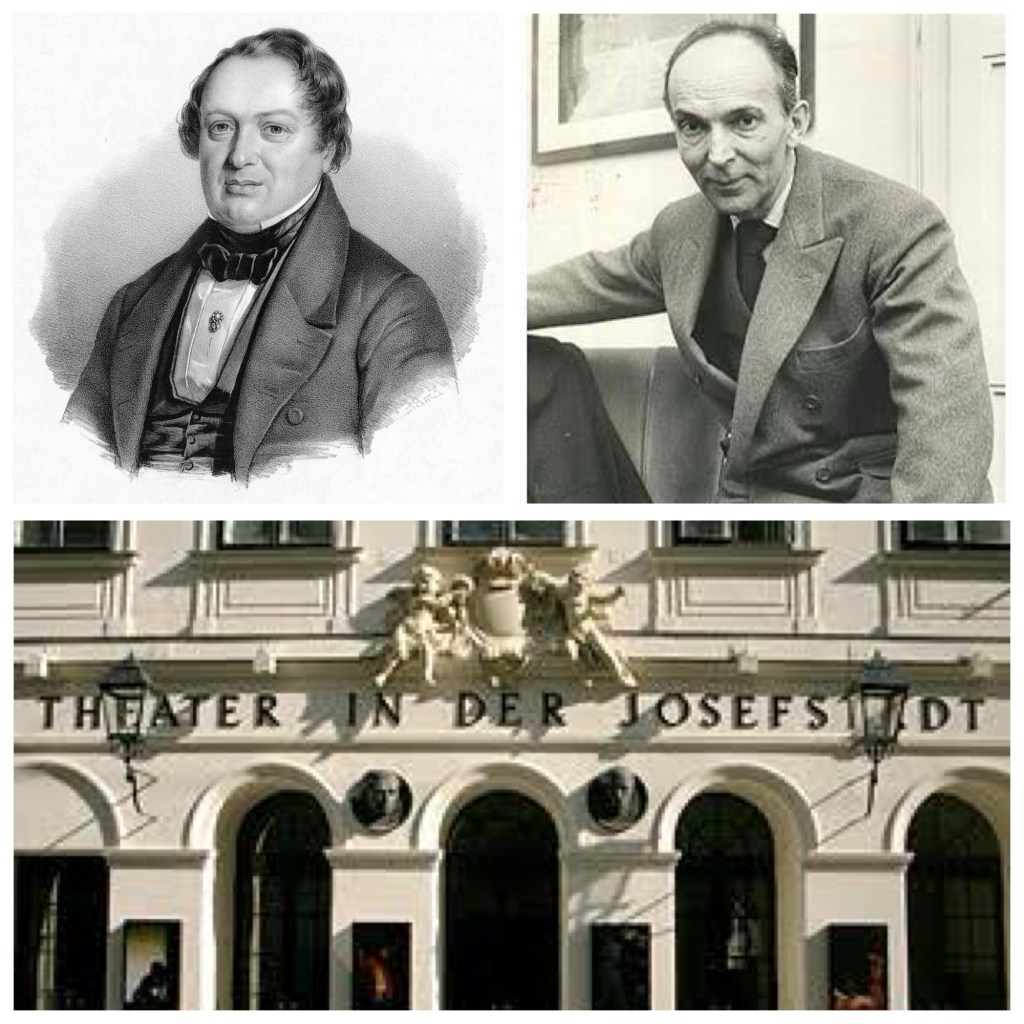

The Consecration of the House Op 124

In 1822, towards the end of his life, Beethoven was asked to provide a new overture for the reopening of the Theater in der Josefstadt in Vienna. Composed in September and premiered there on 3 October 1822, The Consecration of the House marked a festive new beginning for the theatre and also for Beethoven, who had recently emerged from a period of creative difficulty. The first performance was officially conducted by Beethoven himself, despite his near-total deafness, with the theatre’s musical director, Joseph Franz Gläser, discreetly guiding the players from within the orchestra.

The overture reveals Beethoven’s deep admiration for earlier masters, especially J. S. Bach and Handel. Its impressive slow introduction and lively fugal writing recall Baroque ceremonial music, yet the harmonic boldness and structural tension clearly belong to Beethoven’s late style. In this way, the work becomes a bridge between past and present: a tribute to the contrapuntal craft of the Baroque and a showcase of Beethoven’s own late-period experimentation and architectural control. It is often regarded as his last purely orchestral overture.

Beethoven valued the piece highly enough to reuse it as the curtain-raiser for his historic 1824 concert, which introduced the Ninth Symphony to the world. Scored for pairs of woodwinds (2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons), a bright and powerful brass section (4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones), timpani, and strings, the overture combines grandeur, rhythmic drive, and contrapuntal brilliance.The Consecration of the House stands as a radiant statement of Beethoven’s mature orchestral voice.

In Conclusion

Beethoven’s music traces a remarkable journey from youthful brilliance to profound late‑style reflection. Across dance sets, sonatas, overtures, and symphonies, he transformed familiar forms into works of striking contrast and emotional depth. His ability to turn personal struggle into universal expression ensures that his voice remains vivid and compelling, a reminder of art’s enduring power to speak across generations.

Leave a comment