Germany’s Weimar Republic (1919–1933) was born out of defeat and revolution. The Kaiser abdicated, uprisings shook the streets, and a fragile constitution was drafted in Weimar. Politically, the republic was unstable – haunted by reparations, hyperinflation, and extremist violence. Yet culturally, it was dazzling. Berlin became the epicentre of modernity, a city where composers, playwrights, and cabaret artists forged new idioms that reflected both fragility and vitality. This paradox – crisis and creativity intertwined – defined the music of the era. Figures as different as Paul Hindemith, Friedrich Hollaender, Ferruccio Busoni, Richard Strauss, and Kurt Weill each captured a facet of Weimar’s restless spirit.

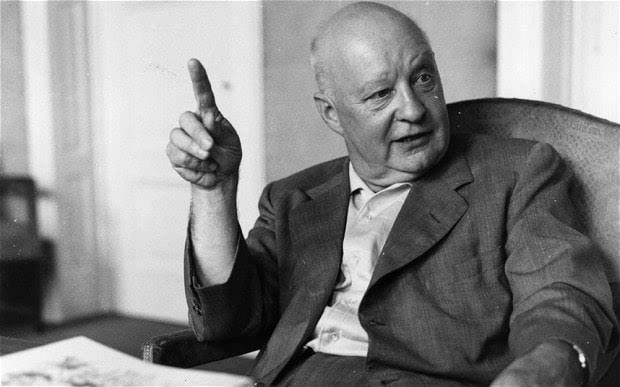

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963)

Neues vom Tage Overture (1929)

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Werner Andres Albert (conductor)

Friedrich Hollaender (1896-1976)

Wit Wollen Alle Wieder Kinder Sein! (1921)

Ute Lemper

Matrix Ensemble

Robert Ziegler (conductor)

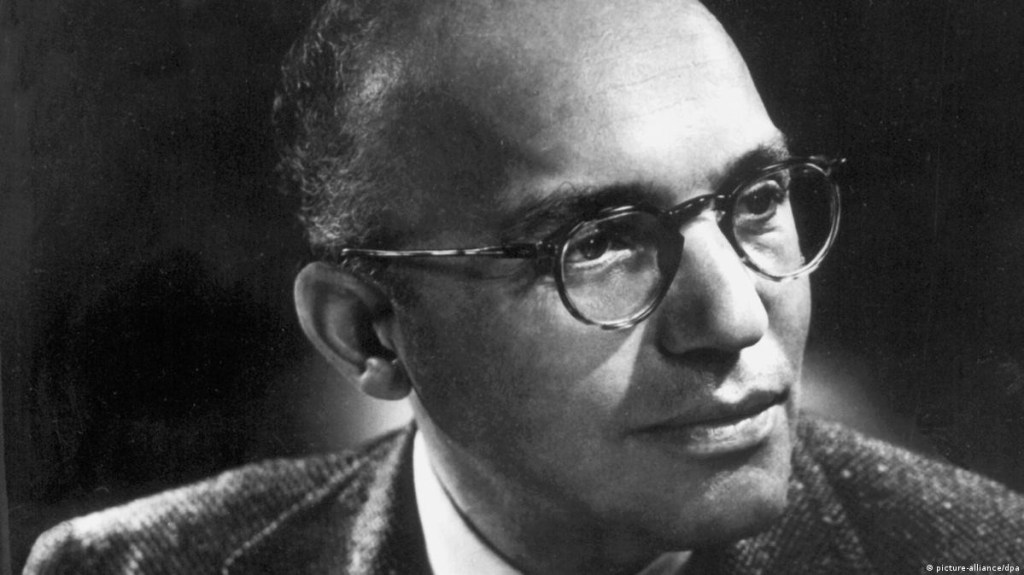

Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924)

Orchestral Suite No 2: Op 34a BV242: (1894-1895) Introduction

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra

Neeme Järvi (conductor)

Kurt Weill (1900–1950)

Mack The Knife from The Threepenny Opera (1928).

Gerald Price

Decca Original Broadway recording (1954)

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Die ägyptische Helena (1928)

Gwyneth Jones (soprano)

Matti Kastu (tenor)

Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Antal Dorati (conductor)

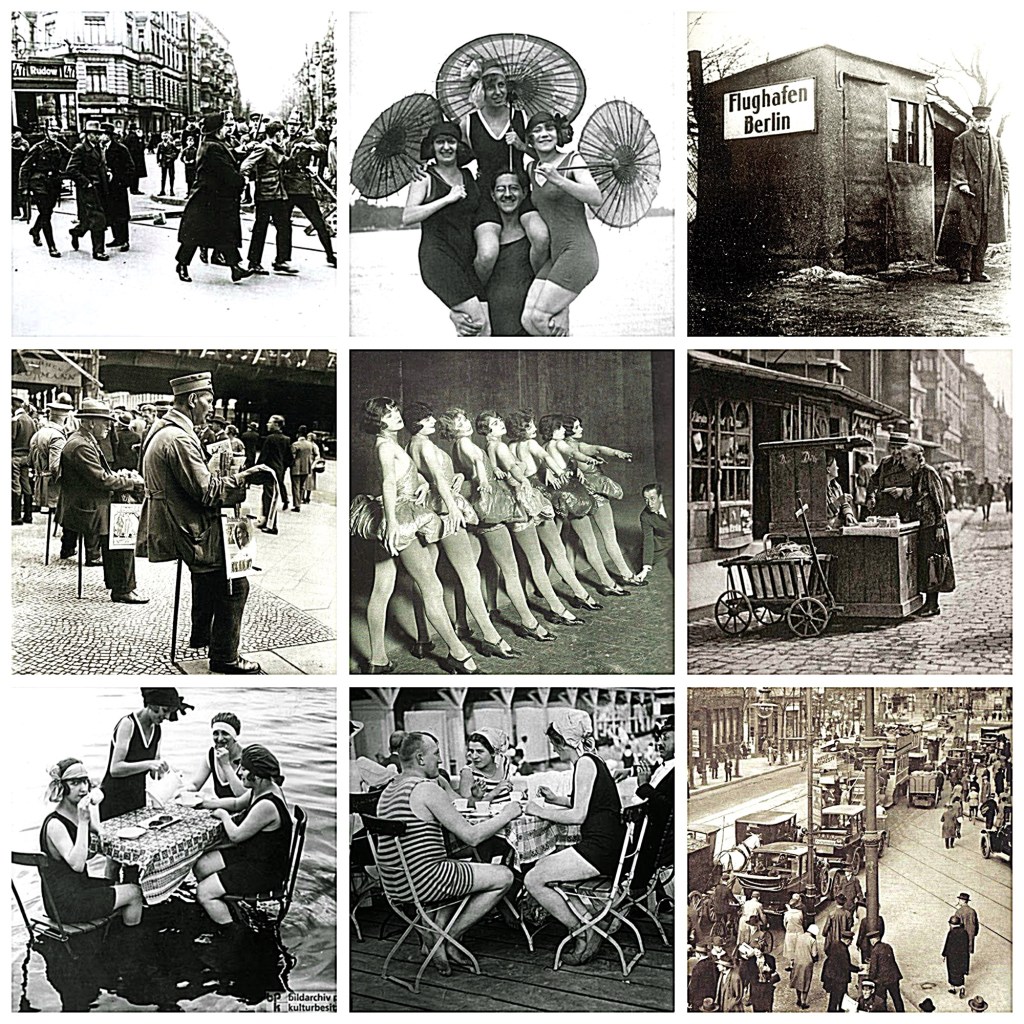

Berlin: A Magnet for Modernity

Before 1918, Vienna had dominated German‑speaking cultural life. After the war, Berlin surged forward. The city premiered Ernst Krenek’s jazz‑inflected Jonny spielt auf and Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve‑tone works. Franz Schreker directed the Hochschule für Musik, while Otto Klemperer staged daring productions at the Kroll Opera. Historian Peter Gay described Berlin as a magnet, pulling in composers, writers, and actors from across Europe. In this ferment, Hindemith turned toward ‘Neue Sachlichkeit’ – a cooler, objective style. Busoni dreamed of a ‘New Classicality.’ Strauss presided as grandee. Weill and Brecht skewered capitalism with razor‑edged satire. And in smoky cabarets, Hollaender’s chansons offered ironic intimacy. Berlin embodied the contradictions of Weimar: Bauhaus modernism alongside squalid tenements, exuberant nightlife against a backdrop of political violence.

Hindemith: Craft and Satire

Paul Hindemith embodied Weimar modernism. A violist, conductor, and theorist, he championed clarity and functionality. His Kammermusik series blended Bach‑like rigour with modern idioms, mirroring the republic’s ethos of sober reconstruction. His comic opera Neues vom Tage (1929) satirised celebrity culture and marriage. Its overture sparkled with wit, while a notorious bath‑scene scandalised audiences and outraged Nazi cultural figures. Hindemith’s ability to fuse serious craft with playful parody captured the paradox of Weimar culture: rigorous yet irreverent.

Hollaender: Cabaret Irony

Friedrich Hollaender rose to fame in Berlin’s cabaret scene. His 1921 chanson Wir wollen alle wieder Kinder sein! (We All Want to Be Children Again) epitomised Weimar irony – playful, nostalgic, yet tinged with melancholy. His greatest triumph came with The Blue Angel (1930). Marlene Dietrich’s performance of Hollaender’s Falling in Love Again became iconic, its refrain – ‘Never wanted to, what am I to do?’ – capturing the bittersweet hedonism of Weimar cabaret. Exiled to Hollywood in 1933, Hollaender composed for Warner Bros., but his Berlin songs remain quintessential expressions of fragile joy amid crisis.

Busoni: Philosopher of Modernism

Ferruccio Busoni, though Italian by birth, became a central figure in Berlin. A virtuoso pianist and theorist, he advocated ‘Young Classicism,’ blending tradition with innovation. His Orchestral Suite No. 2 (Geharnischte Suite) evoked martial imagery with monumental orchestration, while his unfinished opera Doktor Faust distilled metaphysical unease into sound. Busoni’s writings on free tonality influenced Schoenberg, Weill, and Hindemith. Less sensational than serialism, his intellectual modernism provided a philosophical foundation for Weimar’s musical ferment.

Strauss: Ambiguous Grandee

Richard Strauss occupied an ambiguous role. Once scandalous with Salome, he now seemed almost conservative. His opera Die ägyptische Helena (1928) reimagined Helen of Troy, blending mythological grandeur with psychological depth. Critics admired its orchestration but found the libretto convoluted. Strauss presided over a repertory where tradition and experiment collided, mirroring the republic’s oscillation between innovation and reaction. His later fraught role under the Nazis underscores the dangers of cultural politics, but in Weimar he embodied the establishment grandee whose ambiguous modernism reflected the republic’s precarious balance.

Weill: Satire and Social Critique

Kurt Weill was the quintessential Weimar composer of socially engaged music. Collaborating with Bertolt Brecht, he created The Threepenny Opera (1928), whose ballad Mack the Knife juxtaposed cheerful melody with violent subject matter. It became a global standard, epitomising Weill’s accessible yet biting critique of bourgeois society. Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (1930) parodied grand opera with acidic foxtrots and the Alabama Song, skewering capitalism and decadence. Forced into exile in 1933, Weill reinvented himself in New York as a Broadway composer, but his Weimar works remain the most incisive, epitomising the republic’s paradoxical vitality.

Decline and Exile

Weimar’s cultural vitality provoked fierce opposition. Nazi ideologues branded modernism ‘degenerate.’ Hindemith, Weill, and Hollaender were attacked; Busoni’s pupils absorbed his theories quietly while brasher idioms filled cafés. After 1933, émigrés scattered: Schoenberg to California, Weill to New York, Eisler and Hollaender to Hollywood. The ‘New Objectivity’ movement was over, but its spirit survived in exile.

Epilogue: The Legacy of Weimar

The Weimar Republic’s story is one of paradox: fragility and brilliance, collapse and creativity intertwined. Hindemith embodied sober craft fused with satire; Hollaender captured bittersweet cabaret irony; Busoni offered philosophical modernism; Strauss presided as ambiguous grandee; and Weill forged socially engaged satire. Together, they illustrate the extraordinary range of Weimar music, from chamber rigor to torch songs, from mythological opera to proletarian ballads. Berlin’s cabarets, concert halls, and theatres embodied a society wrestling with dislocation but daring to imagine new forms of art, music, and thought. In retrospect, Weimar reminds us that democracy, even in its most precarious form, can unleash extraordinary cultural vitality. Its echoes persist today – in Broadway, Hollywood, and avant‑garde movements – testimony to the power of art to reflect, critique, and transcend crisis.

Leave a comment