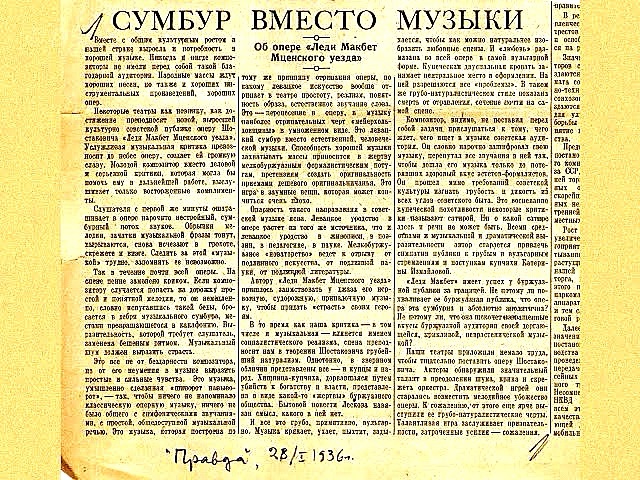

On a cold January morning in 1936, Dmitri Shostakovich opened Pravda to find his name splashed across the front page—not in praise, but in condemnation. His opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, once hailed as daring and modern, was now branded ‘muddle instead of music.’ Overnight, the young composer became a symbol of danger: too experimental, too Western, too far from the ‘bright, optimistic’ art demanded by Stalin’s cultural doctrine. Shostakovich slept with a packed suitcase by the door, waiting for the knock that might take him to the Gulag. His terror was not unique. Across the Soviet Union, composers navigated a perilous landscape where a single symphony could mean a Stalin Prize – or denunciation, arrest, even death.

This moment crystallises the paradox of Soviet musical life under Stalin: a world of extraordinary creativity, but also of constant fear. Some composers bent their voices to survive, producing patriotic cantatas and folk‑inspired ballets. Others were silenced, their manuscripts confiscated or destroyed. Still others lived double lives, writing ‘safe’ public works while embedding anguish or irony in their private compositions. The story of Soviet music in this era is therefore not only about masterpieces but about survival, suppression, and the stubborn endurance of creativity under tyranny.

Gavriil Popov (1904–1972)

Symphony No 2 Op 39 Motherland II Presto giocosr

USSR Radio and TV Symphony Orchestra

Gennady Provatorov (conductor)

Nikolai Roslavets (1881–1944)

Prelude 5: Maestoso from 24 Preludes for violin and piano

Mark Lubotsky (violin)

Julia Bochkovskaya (piano)

Mieczysław Weinberg (1919–1996)

Symphony No 3 in B minor

City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra

Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla (conductor)

Vsevolod Zaderatsky (1891–1953)

Fugue No 2 in A minor from 24 Preludes and Fugues

Lucas Geniušas (piano)

Alexander Mosolov (1900–1973)

Symphony No 5

Moscow Symphony Orchestra

Arthur Arnold (conductor)

Stalin’s Cultural Machinery

By the early 1930s, Stalin had transformed culture into a weapon of ideology. The doctrine of Socialist Realism demanded art that was accessible, optimistic, and patriotic. Music had to uplift the masses, glorify the state, and avoid ambiguity. Anything experimental – atonality, dissonance, or Western modernism – was branded ‘formalism,’ a dangerous deviation.

The system worked through both carrot and stick. The Stalin Prize, awarded to works that embodied Socialist Realism, brought prestige, money, and safety. But denunciations in Pravda or resolutions from the Union of Soviet Composers could destroy careers overnight. Institutions became enforcers: conservatories, unions, and committees dictated repertoire, canceled premieres, and demanded ‘self‑criticism’ from accused composers.

This machinery created a dual legacy: masterpieces born under pressure, and entire voices erased from history. It also created a climate of fear and uncertainty. Careers could rise or collapse overnight depending on political tides. Contact with Western modernism was restricted, though some influences filtered through clandestinely. The state funded orchestras, conservatories, and publishing houses, giving composers resources – if they complied. But the price of support was surveillance, censorship, and ideological oversight. For many, repression proved overwhelming, cutting short careers and silencing voices that might have reshaped twentieth‑century music.

Alexander Mosolov

Mosolov seemed destined to be a star of the Soviet avant‑garde. His Iron Foundry (1927) captured the industrial roar of the new age, a futurist anthem that thrilled audiences abroad. Yet by the late 1930s, Mosolov’s modernism was no longer tolerated. Expelled from the Composers’ Union and arrested, he spent time in the Gulag. When he emerged, the fire of his early experiments had been extinguished. He turned instead to folk‑inspired suites, conforming to Socialist Realism and abandoning the radical voice that had once defined him. His late Symphony No. 5, rediscovered only in 2020, shows a reconciled but still vivid voice – bridging avant‑garde beginnings with Socialist Realist constraints.

Gavriil Popov

Popov’s Symphony No. 1 (1935) was hailed by musicians but quickly banned for ‘formalism,’ its daring harmonies deemed ideologically suspect. Popov was forced to retreat into safer genres, writing patriotic works and chamber music that aligned with state expectations. His Symphony No. 2 ‘Motherland’ (1943–44) reflects both wartime fervor and the struggle to reconcile avant‑garde instincts with Soviet demands. Popov’s career embodies the tension between artistic freedom and political control: his early avant‑garde works remain landmarks of modernist composition, while his later symphonies show how creativity survived under censorship.

Nikolai Roslavets

Older than Mosolov and Popov, Roslavets had pioneered a new harmonic language he called ‘synthetic chords.’His orchestral and chamber works shimmered with modernist color, but his innovations placed him at odds with Stalin’s cultural doctrine. Stripped of posts and marginalized, Roslavets saw his works suppressed and his reputation erased. Only decades later would scholars and performers begin to rediscover the richness of his music. His 24 Preludes for Violin and Piano (1941–42), published posthumously in 1990, reveal his enduring originality, balancing atonal modernism with moments of tonal reference.

Vsevolod Zaderatsky

Zaderatsky endured perhaps the most harrowing fate. Arrested multiple times, his manuscripts were confiscated or destroyed, leaving him to compose under impossible conditions. In prison, he wrote his monumental 24 Preludes and Fugues (1937–39), a cycle that predates Shostakovich’s famous Op. 87 by more than a decade. Smuggled from the gulag, these works stand as a testament to resilience, music written against erasure. His style blends late‑Romantic idioms with modernist elements, showing kinship with Scriabin and Rachmaninoff but with a uniquely personal voice. Today, his prison‑born cycle is recognized as a precursor to Shostakovich’s, restoring Zaderatsky’s voice as a composer nearly erased by Soviet repression.

Mieczysław Weinberg

Weinberg fled Nazi persecution to Moscow, where he became a close friend of Shostakovich. His life was marked by exile, tragedy, and survival. Arrested in 1953 during Stalin’s anti‑Semitic campaign, he was released after Stalin’s death thanks in part to Shostakovich’s intervention. His Symphony No. 3 (1949–50, revised 1959) blends Jewish and Eastern European folk idioms with Soviet symphonic tradition, marking him as one of the most significant yet long‑overlooked voices of the century. Weinberg composed prolifically – 22 symphonies, 17 string quartets, 7 operas – but lived in Shostakovich’s shadow. Only in recent decades has his music been rediscovered, revealing a hidden master whose voice had been muted by circumstance.

Mechanisms of Erasure

Repression was not only about arrests. It was systemic.

- Programming politics: Premieres canceled, works withdrawn, manuscripts confiscated.

- Prize culture: Stalin Prizes rewarded conformity, punishing deviation.

- Institutional enforcement: The Union of Soviet Composers acted as gatekeeper, demanding ideological purity.

- Public denunciations: Pravda articles branded works ‘formalistic,’ forcing composers into self‑criticism.

This apparatus ensured that Soviet music reflected the state’s image: bright, simple, patriotic. Complexity was suspect; ambiguity was dangerous. Careers could collapse overnight. Fear and uncertainty became everyday realities. Many composers lived double lives – publicly loyal, privately conflicted. Their works are studied today not only as music but as documents of survival under authoritarian control.

Aftermath and Rediscovery

Stalin’s death in March 1953 marked the beginning of a slow thaw in Soviet cultural life. The machinery of censorship did not vanish overnight, but the climate shifted. Composers who had lived under constant threat began to see cautious rehabilitation, while works long suppressed started to re‑emerge.

The late Soviet period and the collapse of the USSR opened archives that had long been sealed. Scholars uncovered manuscripts by Roslavets, Zaderatsky, and Veprik, works once confiscated or hidden. In the 1990s, Roslavets’s scores were digitized and published, allowing performers to explore his synthetic harmonies anew. Zaderatsky’s prison‑composed 24 Preludes and Fugues were finally performed, transforming what had been a private act of survival into a public testament of resilience. Weinberg’s symphonies began to be championed internationally, revealing a hidden master whose voice had been muted by circumstance.

Rediscovery is more than repertoire. It is an act of justice. Each revived score restores a silenced voice to the cultural record, challenging the narrative Stalin sought to impose. When audiences hear Mosolov’s Iron Foundry today, they hear not only a futurist experiment but also a reminder of how quickly innovation was punished. When Zaderatsky’s prison fugues resound in concert halls, they testify to the endurance of creativity under oppression.

Conclusion: Echoes of Silence

To hear these rediscovered works in the concert hall is to encounter more than music – it is to step into history. Each symphony, prelude, or fugue carries with it the weight of survival, the shadow of censorship, and the quiet defiance of creativity under tyranny.

For audiences today, these performances are more than aesthetic experiences – they are acts of remembrance. They restore erased voices to the cultural record, challenging the narrative Stalin sought to impose. They remind us that survival was not guaranteed, that brilliance was often punished, and that silence was enforced with devastating consequences. Yet they also affirm that creativity endures, that music can outlast repression, and that forgotten voices can return to speak with urgency and power.

In bringing these works back to life, we do more than expand the repertoire – we honor resilience, reclaim memory, and ensure that the symphonies of silence are transformed into symphonies of survival.

Leave a comment