Cuba’s classical music under Fidel Castro’s regime tells a captivating tale of cultural fusion, state support, and creative endurance. From the 1959 revolution through economic isolation and scarcity, composers wove European sophistication with Afro-Cuban rhythms, navigating strict ideological lines while producing internationally acclaimed works. This article traces the regime’s arc, classical music’s development, and spotlights five key figures: Ignacio Cervantes, Ernesto Lecuona, Amadeo Roldán, Leo Brouwer, and Carlos Fariñas.

Leo Brouwer (b. 1939):

Concierto Elegiano: Toccata (1986)

Chappelle Musicale decTournai

Denis Sung-Ho (conductor)

Amadeo Roldán (1900–1939):

Three Small Poems (1927)

National Symphony Orchestra

Ignacio Cervantes (1847–1905):

Los Tres Golpes (1870–1875)

Raptus Ensemble

Carlos Fariñas (1934–2002):

Punto Y Tonados (1980-81)

National Symphony Orchestra

Enrique Peres Mesa (conductor)

Ernesto Lecuona (1896–1963):

Rapsodia Cubana (1932)

Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra

Thomas Tirino (piano)

Michael Bartos ( conductor)

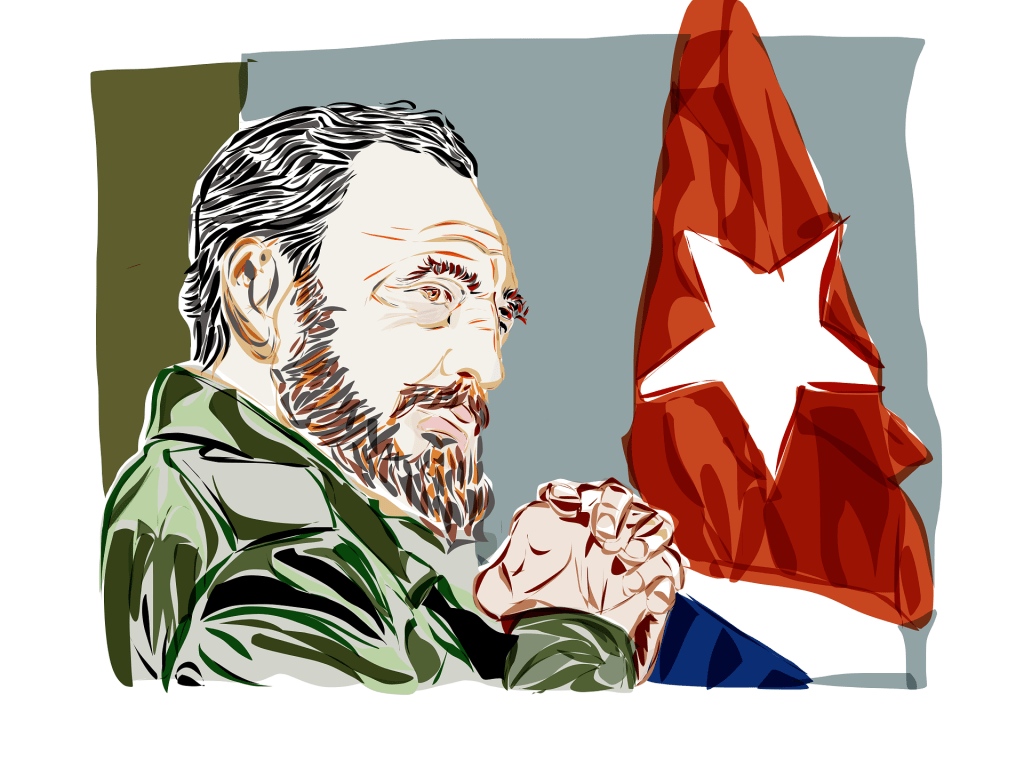

Castro’s Revolution

Fidel Castro assumed power on January 1, 1959, when his guerrilla army forced the resignation of Fulgencio Batista after years of insurgency. As Prime Minister he quickly introduced sweeping socialist reforms, nationalising factories, banks, and farms, redistributing land to peasants, and aligning Cuba with the Soviet Union. The United States responded with a trade embargo in 1960 and the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, which reinforced Castro’s defiance. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 placed the island at the centre of Cold War tensions, resolved only after secret U.S. concessions in Turkey.

By 1976 Castro consolidated authority as President of the Council of State and Ministers, combining loyalty to Moscow with a role in the Non‑Aligned Movement. Ambitious social programmes followed, including literacy campaigns that eradicated illiteracy and universal healthcare that extended to rural communities. Yet economic fragility persisted: the Mariel boatlift of 1980 saw 125,000 Cubans depart for Florida, and Soviet subsidies masked inefficiencies. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Cuba entered the ‘Special Period,’ marked by shortages, rationing, and a sharp economic decline, mitigated only by tourism and remittances.

Castro’s health declined in the 2000s, leading to a transfer of power to his brother Raúl in 2006 and formal resignation in 2008. His legacy remains contested -praised for poverty reduction, racial equity, and cultural patronage, yet criticised for censorship, repression, and one‑party rule. His dictum, Within the Revolution, everything; against it, nothing, captures the paradox of empowerment and constraint that defined Cuban society under his leadership.

Classical Music in Cuba: Tradition and Transformation

Cuban classical music traces its roots to the sixteenth century, when Spanish settlers introduced sacred and secular traditions to Havana’s cathedrals and salons. Over time, African rhythms and call‑and‑response singing – brought through the transatlantic slave trade – merged with European forms, giving rise to uniquely Cuban genres such as the elegant danzón and the vibrant son. These styles became central to both popular and art music, shaping a creole aesthetic that blurred boundaries long before the twentieth century.

By the nineteenth century, composers infused European refinement with local colour, turning music into a vehicle for nationalist sentiment during Cuba’s independence struggles. The Afrocubanismo movement of the 1920s and 1930s further celebrated Afro‑Cuban heritage, embedding percussion, chants, and folkloric motifs into concert works. This cultural hybridity not only defined Cuba’s musical identity but also laid the groundwork for resilience under later political and economic pressures. Today, Cuban classical music stands as a testament to centuries of fusion – European sophistication, African vitality, and nationalist spirit – resonating far beyond the island and securing its place on the global stage.

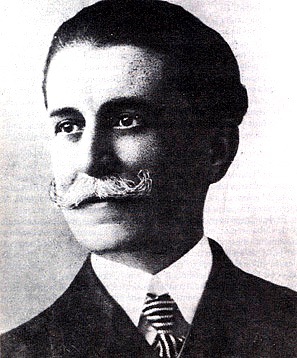

Ignacio Cervantes: Nationalism’s Patriarch

At the heart of nineteenth‑century Cuban classical music stands Ignacio Cervantes (1847–1905), often hailed as the patriarch of Cuban nationalism in art music. Born in Havana to a Spanish father and Cuban mother, Cervantes displayed prodigious talent from an early age. By twelve he was publishing marches; by fourteen he was performing publicly. His brilliance earned him a scholarship to the Paris Conservatoire in 1866, where he studied under Antoine Marmontel, a pedagogue who had trained Chopin, and under the formidable Charles‑Valentin Alkan.

In Paris, Cervantes absorbed the polish of Romantic pianism, but he never abandoned his island roots. His Danzas Cubanas, forty‑one pieces in all, highlight Cuban rhythm within the chamber tradition. Concise yet rhythmically playful, they integrate habanera bass lines and syncopated figures into a Chopinesque piano style. Los Tres Golpes exemplifies this fusion: its playful ‘three knocks’ motif dances over a habanera rhythm, simultaneously charming and subversive in the face of Spanish repression.

Cervantes lived through Cuba’s political upheavals, his sympathies for the rebels during the Ten Years’ War bringing exile and brief imprisonment. Works such as Adiós a Cuba resonate with homesick fervour, blending personal grief with national struggle. Across more than eighty works – songs, chamber pieces, and dances – he forged a distinctly Cuban voice. Though he died in poverty, his music reached Europe, championed by Paderewski, and his fusion of local idioms with classical form became a patriotic model for later generations.

Ernesto Lecuona: The Ambassador in Exile

If Cervantes embodied subtle nationalism, Ernesto Lecuona (1896–1963) turned Cuban music into global spectacle. Havana’s prodigy, he composed at eleven and performed concertos at eighteen.His output exceeded four hundred works, spanning zarzuelas, film scores, orchestral rhapsodies, and piano showpieces.

Pieces such as Malagueña and La Comparsa became international sensations. Malagueña blazes with flamenco fire, while La Comparsa pulses with carnival rhythm, rumba warmth, and impressionist colour. Brilliantly virtuosic yet instantly appealing, these works carried Cuban flair abroad, as Lecuona’s Cuban Boys electrified Paris, London, and New York in the 1930s, selling the sound of Cuba to roaring crowds.

Lecuona’s Rapsodia Cubana (1932) stands as a summation of his achievement, weaving orchestral and pianistic textures through regional idioms from guajira to montuno. His career, however, was shaped by political currents. Though supportive of reforms in the Batista era, he left Cuba after the 1959 revolution, voicing opposition to new cultural policies that curtailed performance venues and centralised recording under EGREM (Empresa de Grabaciones y Ediciones Musicales), Cuba’s state‑run record label. For a time his catalogue was viewed with suspicion, but it was later embraced as part of Cuba’s national heritage. In exile, he continued to serve as a prominent ambassador for Cuban music, even as his work was reinterpreted within the very cultural framework he had resisted.

Castro’s Arts Revolution: Patronage and Paradox

The triumph of Fidel Castro in January 1959 inaugurated a cultural renaissance. Within months, the National Symphony Orchestra was launched; Alicia Alonso was summoned to lead the Ballet Nacional; and the Amadeo Roldán Conservatory expanded under free tuition, minting virtuosos who would be exported worldwide. Classical music was touted as socialist purity, untainted by Yankee pop, with EGREM dictating the presses.

Yet paradox reigned. Santería was vilified as feudal relic, bolero clubs shuttered, and UNEAC (Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba) policed ideological dogma. At the same time, creativity flourished. Harold Gramatges founded the Havana Chamber Orchestra; Juan Blanco pioneered electroacoustic works in the early 1960s; and nueva trova singers such as Silvio Rodríguez and Pablo Milanés strummed introspective socialism through the 1970s. Later, timba and rap prodded the edges of acceptability. Classical heirs of the Grupo de Renovación thrived in this hothouse, daring within the lines drawn by the state.

Leo Brouwer: Revolutionary Virtuoso

Among those heirs, Leo Brouwer (b. 1939) stands as revolutionary virtuoso. Descended from a musical dynasty, Brouwer mastered the tightrope of innovation and ideology. After the revolution, he helmed the National Guitar School, taught at the Amadeo Roldán Conservatory, and even conducted the National Symphony. His early folk miniatures gave way to avant‑garde experiments with chance music and aleatoric textures.

International studies at Juilliard and in the Soviet Union shaped Leo Brouwer’s distinctive voice. Works such as Sonata Elegíaca: Toccata (1986, Guitar Concerto III) reveal his command of idiom and virtuosity, memorably heard in Julian Bream’s BBC performance under Brouwer’s direction. The concerto integrates danzón rhythms with brilliant guitar writing, serving as both homage to Bream and affirmation of Cuban tradition. Earlier, Elogio de la Danza (1964) offered a percussive tribute to Afro‑Cuban roots. Brouwer’s collaborations, including a notable encounter with the Rolling Stones in Havana during the 1980s, underscored his role as a leading ambassador of Cuban guitar on the international stage.

Carlos Fariñas: Electroacoustic Pioneer

Carlos Fariñas (1934–2002) was a central figure in Cuba’s modernist movement. Trained at the Havana Conservatorio, Indiana University, and the Moscow Conservatory, he combined neoclassical clarity, serialist discipline, and folkloric elements in his work. His Tiento II (1969), which integrates Renaissance polyphony with tape techniques, won international recognition in Paris and marked Cuba’s entry into electroacoustic music. Fariñas later established the Electroacoustic Music Laboratory in Havana, fostering new generations of composers who explored tape, synthesis, and live electronics.

His Punto y Tonadas (1980–81) reimagines folk songs from Matanzas through electronic timbres, affirming the place of Cuban traditions in contemporary concert life. Alongside Leo Brouwer, Fariñas helped define the 1960s modernist movement, demonstrating how state institutions could support innovation in art music.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 ushered in Cuba’s ‘Special Period,’ a time of severe economic hardship. Despite shortages, conservatories remained active, students continued their training, and ensembles toured abroad to sustain international connections. Nueva trova musicians such as Carlos Varela voiced social commentary in allegorical form, while classical groups maintained visibility through performances in Spain, Italy, and France, with parallel activity in exile communities abroad.

Cuban violinist Amelia Febles Díaz

In Conclusion

Today, Cuba’s classical tradition continues to resonate internationally. The Amadeo Roldán Theatre in Havana hosts premieres, and composers such as Juan Piñera and Edesio Alejandro pursue new directions in minimalism, multimedia, and Afro‑Cuban idioms. This lineage – from Cervantes’ salon dances and Lecuona’s rhapsodies to Roldán’s percussion works, Brouwer’s guitar concertos, and Fariñas’ electroacoustic experiments – illustrates a continuous process of adaptation and renewal.

Cuban classical music has endured through colonial legacies, revolutionary patronage, and post‑Soviet austerity. While cultural policies imposed constraints, they also provided infrastructure that nurtured talent. The result is a tradition that is distinctively Cuban: rhythmically vital, harmonically adventurous, and globally relevant.

Leave a comment