Few rivalries in the history of music have been as enduring, as widely misunderstood, or as culturally significant as the one between Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri. Their names remain inextricably linked – not just because they were contemporaries in the bustling musical scene of late 18th-century Vienna, but due to the persistent legend that Salieri, consumed by envy, undermined Mozart’s career and may have even poisoned him. This dramatic tale, popularized by Peter Shaffer’s 1979 play Amadeus and Miloš Forman’s sumptuous 1984 film adaptation, has left a far greater mark on cultural memory than historical reality ever did.

The reality, however, is far more nuanced. Mozart and Salieri were contemporaries navigating the fiercely competitive landscape of Viennese opera. They respected each other’s talents, occasionally collaborated, and shared a relationship marked by both admiration and rivalry. To truly grasp the nature of their connection, it’s essential to delve into their biographies, their musical legacies, the myths that have grown around them, and the timeless fascination with envy and genius. By contrasting the historical record with the dramatised myth of Amadeus, we can see how fact and fiction intertwine – and why this story continues to captivate audiences to this day.

Antonio Salieri

Overture to La scuola de’ gelosi – School for the Jealous (1778)

L’Arte del Mondo

Werner Ehrhardt (conductor)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Overture to Le nozze di Figaro – Marriage of Figaro (1786)

Royal Festival Orchestra

William Bowles (conductor)

Antonio Salieri

Requiem in C minor (1804) – Kyrie

Gulbenkian Choir and Orchestra

Lawrence Foster (conductor)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Requiem (1791) – Kyrie

Swedish Radio Choir

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Claudio Abbado (conductor)

Antonio Salieri

Symphony in D major “La Veneziana” (1770s) IV Presto

Chopin Chamber Orchestra

Winston Dan Vogel (conductor)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Symphony No. 41 ‘Jupiter’ (1788)

The English Concert

Trevor Pinnock (conductor)

The Lives of Mozart and Salieri

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

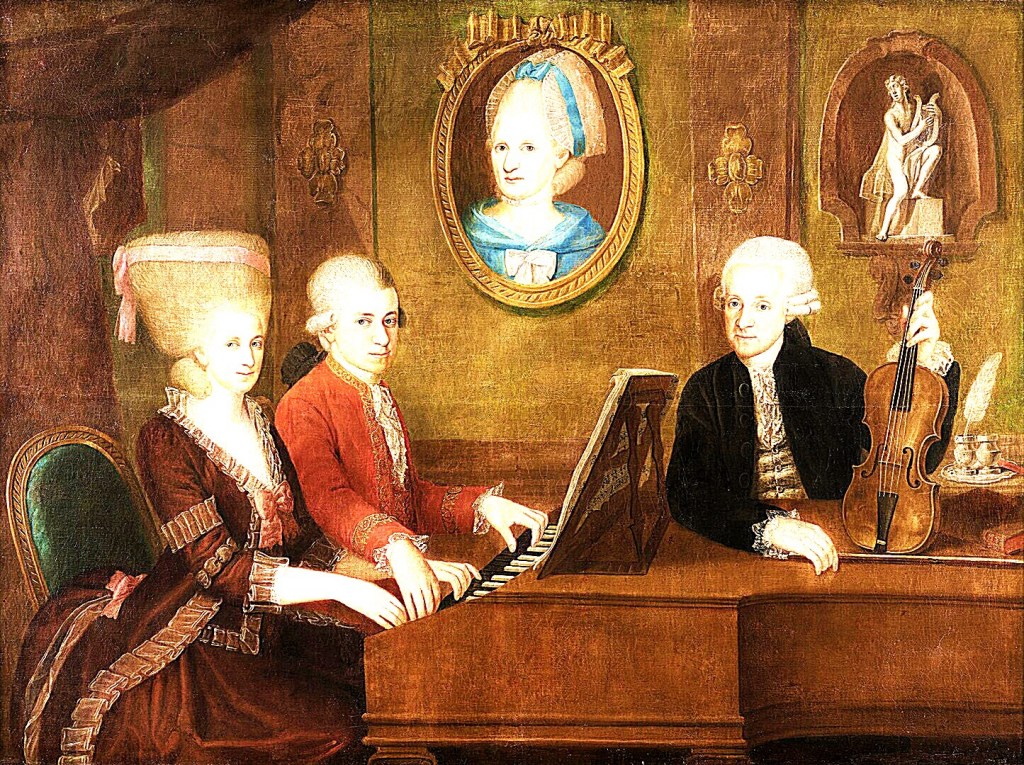

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born in Salzburg in 1756, the son of Leopold Mozart – a violinist and composer who quickly recognized his son’s extraordinary talent. By the age of five, Mozart was already composing music, and by six, he was touring Europe alongside his sister, Nannerl, astonishing courts and audiences with his prodigious abilities. His childhood was a whirlwind of performances before royalty and nobility, cementing his reputation as one of history’s most remarkable child prodigies.

As Mozart grew older, his genius flourished across every musical genre—symphonies, concertos, chamber music, sacred works, and, above all, opera. His operas – The Marriage of Figaro (1786), Don Giovanni (1787), and The Magic Flute (1791) – remain cornerstones of the operatic repertoire, celebrated for their dramatic depth, melodic brilliance, and emotional richness.

In 1781, Mozart moved to Vienna in pursuit of artistic independence, free from the constraints of aristocratic patronage. While he thrived creatively, financial stability eluded him, as he often lived beyond his means. Despite his unparalleled talent, he never secured a stable court position like his contemporary, Salieri. Mozart’s life was tragically cut short in 1791 at just 35 years old, likely due to illness. Yet, his legacy endures through a body of work that defines the Classical era.

Antonio Salieri (1750–1825)

Salieri was born in Legnago, near Verona, in 1750. Orphaned as a teenager, he moved to Vienna under the patronage of composer Florian Gassmann. Salieri quickly rose in the imperial court, benefiting from his skill in opera composition and his ability to adapt to different languages and styles.

By the 1780s, he was Kapellmeister (court music director), a prestigious position he held for decades. Salieri composed operas in Italian, French, and German, including Les Danaïdes (1784), Tarare (1787), and Axur, re d’Ormus (1788). His works were admired for their grandeur, theatricality, and orchestral colour.

He was also a renowned teacher, instructing Beethoven, Schubert, Liszt, Meyerbeer, and even Mozart’s son Franz Xaver. His influence as a pedagogue was immense, shaping the next generation of composers. Salieri retired from opera in the early nineteenth century but remained active as a teacher and conductor. He died in Vienna in 1825 at the age of 74, respected but overshadowed by the growing legend of Mozart.

The Real Relationship

Mozart and Salieri were contemporaries in Vienna, both competing for patronage and prestige in the imperial court. Salieri, as Kapellmeister, had institutional power and connections, while Mozart, though immensely talented, struggled to secure stable employment. This naturally created tension, as both sought opportunities in the same musical environment.

Despite competition, evidence shows they respected each other’s work. In 1785, they collaborated with composer Cornetti on a cantata (Per la ricuperata salute di Ofelia) celebrating the recovery of soprano Nancy Storace. Mozart admired Salieri’s operas, particularly Axur, re d’Ormus and Tarare. He attended performances, praised their dramatic power, and even conducted Salieri’s overtures in concert.

Salieri, for his part, recognized Mozart’s genius. While he may have felt overshadowed, there is no credible evidence he sabotaged Mozart’s career or poisoned him. Their relationship was shaped more by court politics than personal hatred. Mozart’s complaints of ‘Italian cabals’ in letters to his father were likely exaggerated to appease Leopold’s anxieties rather than accurate depictions of Salieri’s actions.

Placed side by side, the contrasts between Mozart and Salieri’s operas are striking.

- French Grandeur vs. Italian Lyricism: Salieri’s Tarare and Les Danaïdes reveal French reformist influence, favouring large choruses and ceremonial spectacle. Mozart leaned toward Italianate lyricism, focusing on character psychology and emotional nuance.

- Orchestration: Salieri employed bold orchestral colours to heighten drama, while Mozart’s orchestration was subtler, weaving instrumental voices into the emotional fabric of his characters.

- Ensemble Writing: Salieri’s ensembles often functioned as tableaux, presenting moral or political statements. Mozart’s ensembles, especially in Figaro, are dynamic conversations in music, layering conflicting emotions simultaneously.

- Themes: Salieri gravitated toward mythic or political subjects; Mozart probed the comedy and tragedy of everyday human life.

These stylistic differences explain both admiration and tension. Mozart respected Salieri’s theatrical power, while Salieri recognized Mozart’s genius in character portrayal. Their operas were not simply rivals but complementary voices in Vienna’s operatic landscape.

The Myth of Rivalry

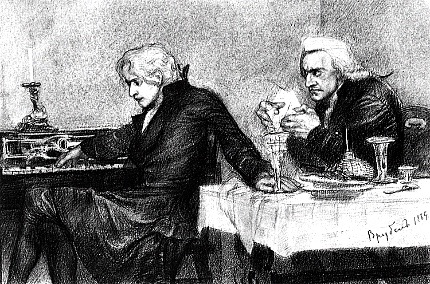

After Mozart’s death, rumours circulated that Salieri had poisoned him. These were fuelled by Mozart’s early death, his financial struggles, and Salieri’s prominence at court. Pushkin’s 1830 play Mozart and Salieri dramatised the rivalry, portraying Salieri as a jealous murderer. Later, Rimsky-Korsakov and others revisited the theme.

Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus (1979) and Miloš Forman’s film (1984) brought the myth to global audiences. In Amadeus, Salieri is consumed by envy, plotting to destroy Mozart as revenge against God. The play dramatises Mozart’s decline, suggesting Salieri commissioned the Requiem to claim it as his own.

The narrative is framed as Salieri’s confession, making him both villain and tragic antihero. The themes of envy, faith, and mediocrity resonate universally, ensuring the story’s enduring appeal – even though it is historically inaccurate.

Amadeus in Scholarship and Culture – Fact and Fiction

Scholars initially had mixed reactions to Amadeus. Looking back, however, the film’s blending of fact and fiction appears less problematic, as its portrayal of Mozart’s decade in Vienna is largely accurate. The sequence of his compositions aligns with history, and key figures such as Salieri, Bonno, and Count Orsini Rosenberg are correctly depicted in their courtly roles.

Romantic Biases

The film weaves together two historical perspectives: it draws from the Romantic-era reception of Mozart – particularly the unfounded claims that Salieri played a role in his death – while depicting events of the late 18th century. Salieri’s portrayal of Mozart as an unparalleled genius reflects the exaggerated admiration more characteristic of 19th-century criticism than the actual Viennese reactions of the 1780s.

The film’s latter half centers on three works cherished by Romantic audiences for their brooding intensity – the Piano Concerto in D minor, K.466; Don Giovanni; and the Requiem – with only The Magic Flute offering contrast, its humour and enchantment brought to the fore. While this selection doesn’t capture the full breadth of Mozart’s late style, it mirrors Salieri’s 1823 recollections, steeped in the Romantic imagination.

The Requiem and Süssmayr

The film portrays Mozart feverishly dictating the Confutatis to a struggling Salieri, desperate to keep pace. In reality, Mozart never dictated this movement to anyone, and it was Franz Xaver Süssmayr – not Salieri – who completed much of the Requiem after Mozart’s death in December 1791. Süssmayr’s influence is clear throughout the score, from orchestration to the finishing of several movements, though his role has long been debated by scholars and performers alike.

Yet the film’s iconic image of Salieri hunched over his desk, overwhelmed by the flood of genius, captures something profound: the awe of witnessing creativity in its most urgent form, the poignancy of unfinished art, and the drama of a masterpiece left incomplete. The Lacrymosa, heard in full at the film’s close, bridges the gap between Mozart the man and Mozart the myth.

In this way, Amadeus doesn’t just dramatise Mozart’s life – it also explores his posthumous legacy, foreshadowing the ongoing debates surrounding the Requiem and illustrating how myth and scholarship together shape our understanding of Mozart’s final work.

Conclusion: Between History and Myth

The story of Mozart and Salieri is a compelling example of how myth can overshadow history. In truth, their relationship was one of professional collegiality: both navigated Vienna’s fiercely competitive musical scene, admired each other’s work, and even collaborated on occasion. Far from being bitter enemies, they were fellow artisans in a shared craft.

Yet the myth of Salieri as Mozart’s envious poisoner proved impossible to resist. Writers and artists – from Pushkin to Rimsky-Korsakov, and later Peter Shaffer in Amadeus – shaped the narrative of envy consuming genius. Miloš Forman’s film adaptation then carried this legend to a global audience. In Amadeus, Salieri becomes the “patron saint of mediocrities,” a tragic figure who recognizes greatness but cannot achieve it himself. The film’s power lies not in its historical accuracy but in its dramatic exploration of envy, faith, creativity, and human vulnerability.

Historically, Salieri did not murder Mozart. He was, in fact, a respected composer and teacher in his own right. But the myth endures because it speaks to a deeper cultural fascination with the drama of genius and the obstacles it faces. When we listen to The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, or the Requiem today, we hear not rivalry but Mozart’s transcendent voice. Salieri, too, deserves recognition – not as a villain, but as a skilled musician and mentor who contributed to the musical landscape of his time.

Ultimately, Amadeus doesn’t tell us what happened; it tells us why we care. It dramatises the timeless struggle between talent and recognition, inspiration and envy, the fleeting nature of life, and the permanence of art. For audiences, this resonance endures: behind every note lies both history and myth, shaping how we experience Mozart’s music today.

For a richer understanding, compare Mozart’s and Salieri’s operas, sacred works, and concert pieces where their styles intersect. Mozart’s brilliance in dramatic characterisation and orchestral colour contrasts with Salieri’s clarity, balance, and courtly refinement. Together, their music offers a window into the vibrant musical world of late 18th-century Vienna.

Leave a comment