The Call of the Highlands

The Jacobite uprisings were not merely political rebellions; they were a struggle for identity, a defiance against the erosion of a way of life. The music of this era – whether sung in the taverns of Edinburgh, hummed in the glens, or later immortalised in grand concert halls – became the heartbeat of a people. It preserved their stories, their sorrows, and their hopes. From the rallying cries of rebellion to the laments of exile, the Jacobite legacy is woven into the very fabric of Scottish music. This programme traces the journey of that legacy, from the battlefields of Culloden to the concert stages of the 19th and 20th centuries. It is a story of how music became a tool for memory and resistance, and ultimately, a celebration of Scottish identity.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847)

Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 56 ‘Scottish Symphony’ (completed 1832)

Apollo Chamber Orchestra

David Chernaik (conductor)

Anne Campbell MacLeod (from a traditional Gaelic tune

The Skye Boat Song

Kings Singers

John McEwen (1868–1948)

Viola Concerto III. Allegro con brio (1901)

Lawrence Power (viola)

BBC National Orchestra of Wales

Martyn Brabbins (conductor)

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759)

Occasional Oratorio HWV 62 (1746)

Lea Desandre (soprano)

Jupiter Ensemble

Thomas Dunford (conductor)

Hamish MacCunn (1868–1916)

The Land of the Mountain and the Flood, Op. 3 (1886)

Scottish National Orchestra

Alexander Gibson (conductor)

The Jacobite Cause: A Struggle for Identity

The Jacobite movement was born from the ashes of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when the Catholic King James II of England (James VII of Scotland) was deposed in favour of his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband, William of Orange. For many in Scotland, particularly in the Gaelic-speaking Highlands, the Stuarts were not just monarchs but symbols of an ancient and legitimate lineage. The Jacobites – named after the Latin Jacobus, for James – believed the Stuart claim to the throne was divine and unassailable.

The movement was deeply rooted in the cultural and religious identity of the Highlands. The suppression of Gaelic language, the dismantling of clan structures, and the imposition of Protestant rule were not merely political acts but attacks on a way of life. The Jacobites, therefore, were not just fighting for a king; they were fighting for the soul of Scotland.

The Uprisings: Defiance and Defeat

The Jacobite cause flared into open rebellion three times: in 1689, 1715, and most famously in 1745. The ’45, led by the charismatic Charles Edward Stuart – Bonnie Prince Charlie – was the last and most dramatic of these uprisings. In a matter of months, the Jacobite army swept through Scotland, captured Edinburgh, and marched deep into England, reaching as far as Derby. For a brief, exhilarating moment, it seemed the Stuarts might reclaim their throne.

But the tide turned. The Jacobites retreated, harried by government forces, and on the cold, windswept moor of Culloden in April 1746, their dreams were shattered. The battle lasted less than an hour, but its consequences would echo for centuries. The British government responded with brutal repression: clans were disarmed, lands confiscated, and Highland culture systematically erased. The wearing of tartan was banned, Gaelic suppressed, and the clan system dismantled.

Yet, the Jacobites did not vanish. Their story lived on in song, in poetry, and in the collective memory of a people. The music of the Jacobite era became a form of resistance, a way to keep the flame of identity alive even in the darkest of times.

Songs of Rebellion: The Music of the Jacobites

In the 18th century, music was the lifeblood of the Jacobite cause. Unlike the grand orchestral works of the concert hall, Jacobite music was born in the oral tradition – sung in taverns, around campfires, and in the homes of the Highland clans. These were not compositions for the elite but anthems of the people, designed to inspire, to rally, and to mourn.

Songs like The White Cockade, Mo Ghile Mear, and Will Ye No Come Back Again? were more than mere tunes; they were political statements, coded messages of loyalty to the Stuart cause. The White Cockade, with its rousing chorus, became a rallying cry for Jacobite supporters, while Mo Ghile Mear – a Gaelic lament – spoke of the longing for the return of Bonnie Prince Charlie. Will Ye No Come Back Again? captured the sorrow of defeat and the hope of return, a theme that would resonate deeply in the years after Culloden.

Satire and Defiance: The Jacobite Wit

The Jacobites were not only skilled in battle but also in wit. Satirical songs like Hey Johnnie Cope mocked the government forces, turning military defeat into a source of humor and defiance. These songs were a way to undermine the authority of the Hanoverian regime, to laugh in the face of oppression, and to keep the spirit of resistance alive.

After Culloden, the tone of Jacobite music shifted. The rallying cries of rebellion gave way to laments – songs of mourning for the fallen, for the exile of Bonnie Prince Charlie, and for the loss of a way of life. These laments, such as The Skye Boat Song, would later become some of the most enduring symbols of the Jacobite legacy.

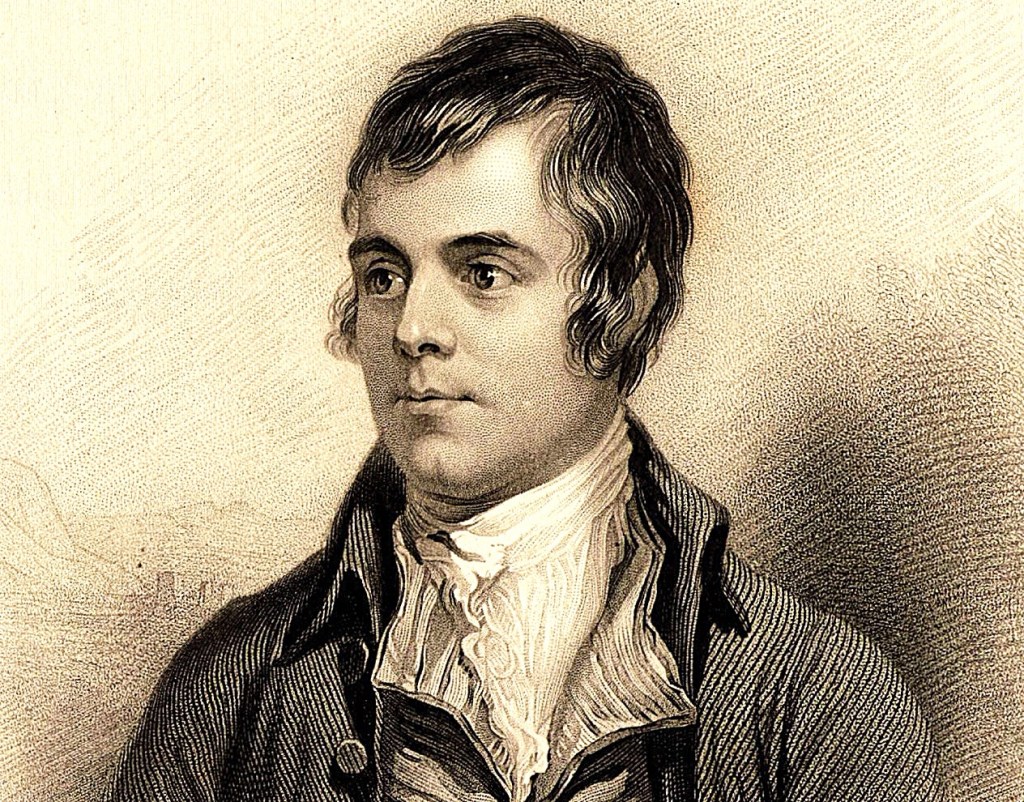

Robert Burns and the Jacobite Memory

By the late 18th century, the Jacobite cause was no longer a political threat but a source of romantic nostalgia. The poet Robert Burns played a pivotal role in this transformation. In 1793, he set the traditional tune Hey Tuttie Tatie to his patriotic text Scots Wha Hae, a song that invoked the spirit of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce but resonated deeply with Jacobite memory. Burns’ work helped to recast the Jacobites not as rebels but as tragic heroes, symbols of a lost Scotland.

Sir Walter Scott and the Jacobite Legend

The early 19th century saw the Jacobite story immortalised in the works of Sir Walter Scott. His novels Waverley (1814), Rob Roy (1817), and The Lady of the Lake (1810) transformed Jacobite history into romantic legend. Scott’s portrayal of the Highlands – its landscapes, its clans, and its turbulent history – captured the imagination of Europe. His works inspired composers like Franz Schubert, whose Lady of the Lake cycle (1815–16) drew on Scott’s romanticized imagery of exile and longing.

Schubert’s Ave Maria, based on Scott’s The Lady of the Lake, became one of the most famous musical tributes to the Jacobite spirit. Though Schubert never visited Scotland, his music evoked the themes of displacement and nostalgia that lay at the heart of the Jacobite experience.

The Celtic Revival

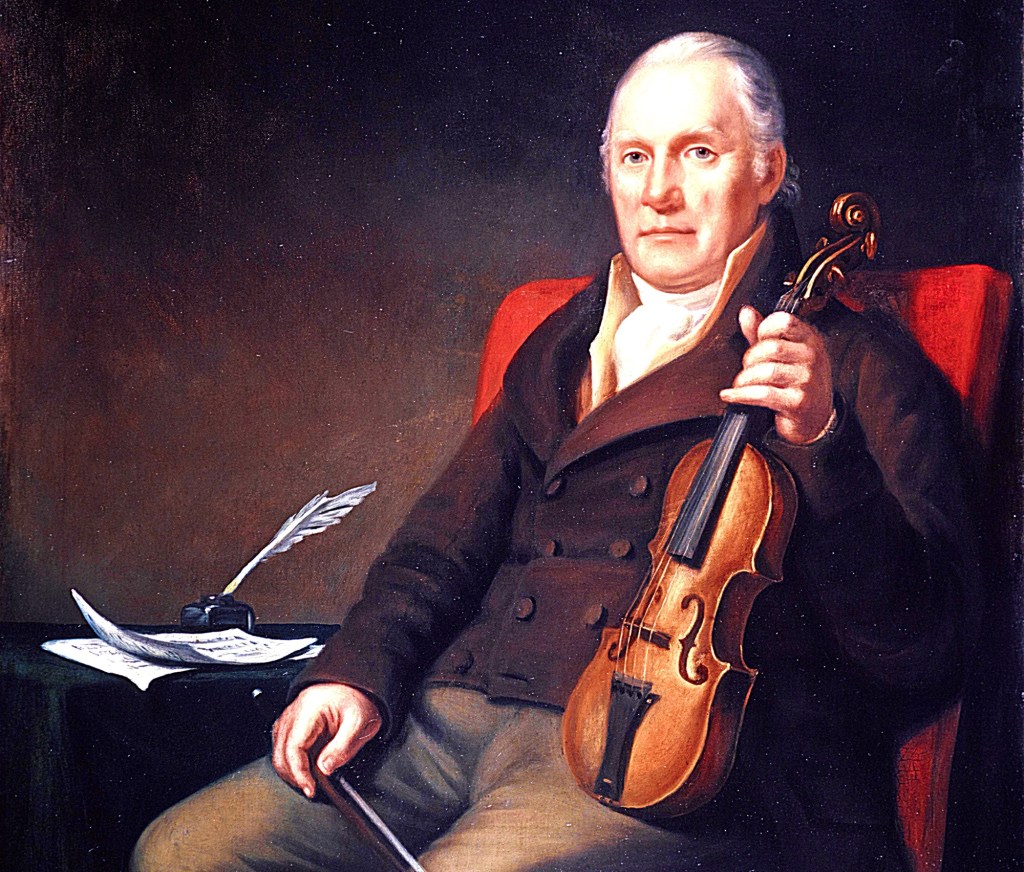

The Victorian era saw a resurgence of interest in Scotland’s cultural heritage. The Celtic Revival, as it came to be known, celebrated Scotland’s past through music, literature, and art. Composers like William Marshall, often called “the Scottish Haydn,” played a crucial role in preserving Highland musical traditions. Marshall’s strathspeys and reels kept the melodies of the Jacobite era alive, blending folk idioms with classical craft.

Mendelssohn and the Scottish Symphony

Felix Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony (1842) is another work deeply influenced by Scotland’s cultural memory. Though not explicitly about the Jacobites, the symphony reflects the Romantic era’s fascination with Scotland’s past. Mendelssohn’s visits to Holyrood Palace and the ruins of Linlithgow Palace, both tied to the Stuart dynasty, inspired him to capture the mood of a Scotland grappling with its history. The symphony’s dramatic contrasts—between stormy conflict and tender lament—mirror the Jacobite experience of defiance, sorrow, and enduring pride.

The Skye Boat Song: A Cultural Icon

Perhaps no song better captures the romanticized legacy of the Jacobites than The Skye Boat Song. Written in 1884 by Sir Harold Boulton, the song commemorates Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape after Culloden, aided by the legendary Flora MacDonald. Though not an authentic Jacobite composition, the song became a cultural emblem, turning the prince’s flight into a symbol of hope and resilience.

By the 20th century, The Skye Boat Song had entered the canon of Scottish heritage, appearing in school songbooks, recordings, and even television soundtracks. It is a testament to the enduring power of the Jacobite myth, a story of loyalty, sacrifice, and the unbreakable spirit of the Highlands.

Sir John Blackwood McEwen (1868 – 1948)

John McEwen Viola Concerto: The Scottish Romantic Tradition

John McEwen’s Viola Concerto (1901) is a work that embodies the Scottish Romantic tradition. While not overtly nationalist or Jacobite, the concerto reflects McEwen’s Scottish identity through its lyrical, folk-like themes and evocative orchestration. The concerto’s elegiac lyricism aligns with the Scottish tradition of lament, offering a musical portrait of a landscape shaped by history and memory.

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Handel and the Triumph of Hanover

While much of Jacobite music emerged from the folk tradition, the cause also inspired classical composers. George Frideric Handel’s Occasional Oratorio (1746) was written as a direct response to the Jacobite threat. Commissioned by the Hanoverian monarchy, the oratorio is a triumphant celebration of divine providence and national unity, a musical counterpoint to the Jacobite rebellion.

Hamish MacCunn and the Land of the Mountain and the Flood

Hamish MacCunn’s The Land of the Mountain and the Flood (1887) is another iconic work of the Victorian era. Inspired by Sir Walter Scott’s poetry, the overture celebrates Scotland’s rugged landscapes and cultural heritage. While not explicitly Jacobite, it belongs to the same Romantic nationalist tradition that kept the memory of the Jacobites alive, turning Scotland’s past into a source of pride and identity.

The Enduring Legacy of the Jacobites

The Jacobite uprisings may have ended in defeat, but their legacy lives on in the music of Scotland. From the folk songs of the 18th century to the concert halls of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Jacobite story has been preserved, reinterpreted, and celebrated. It is a story of resistance, of cultural pride, and of the enduring power of music to keep history alive.

Whether in the laments of exile, the triumphant overtures of Romantic nationalism, or the modern works that explore themes of persecution and survival, we are reminded that music is more than sound. It is memory. It is identity. And it is the voice of a people who refused to be forgotten.

Leave a comment