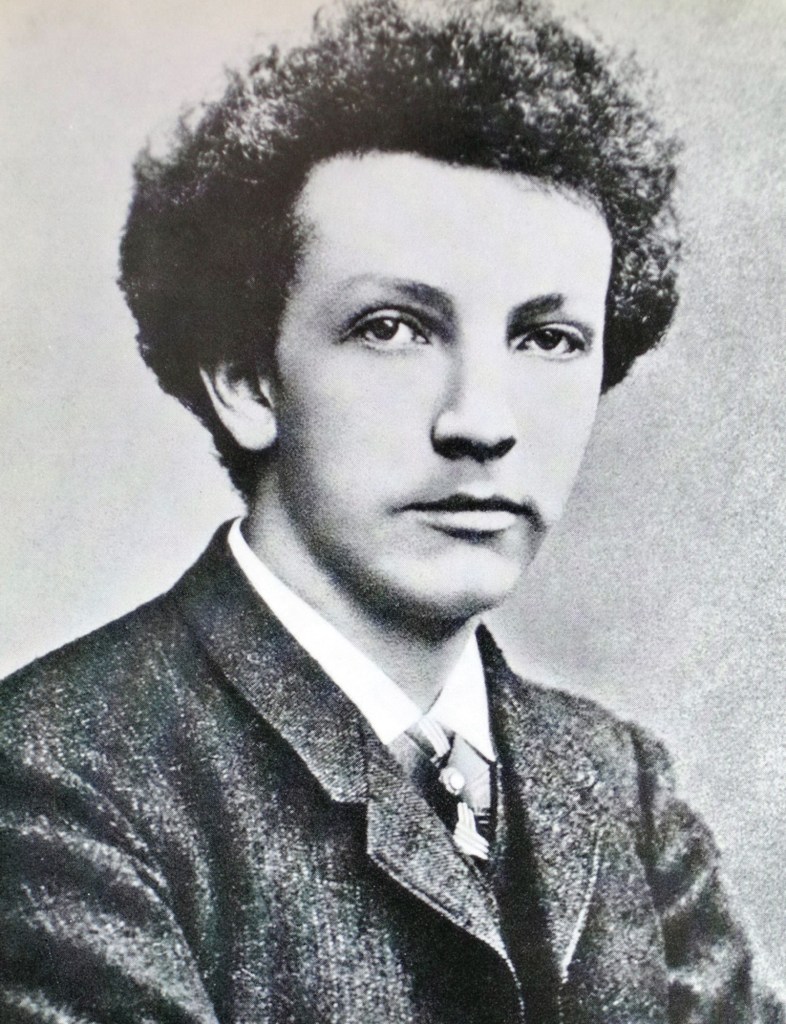

Richard Strauss is known for his tone poems such as Don Juan (1888) and Also sprach Zarathustra (1896) and his operas like Salome (1905), Elektra (1909), and Der Rosenkavalier (1911). His style blends late Romanticism with early modernism and he was recognised as a leading conductor, performing with orchestras all over Europe. He co-founded the Salzburg Festival in 1920 and enjoyed a career lasting almost 80 years.

In the mid-1800s, the tone poem was revolutionary in music. It was pioneered by Franz Liszt, who wanted to blend music with literature, myths, and art. Unlike traditional symphonies, tone poems told stories and delved into emotions, often in just one movement. By the 1880s, the genre was becoming tired due to its ties to the traditional musical structures but Richard Strauss came along and created some innovative works that pushed orchestral techniques and connected with big intellectual ideas, especially Nietzsche’s philosophy. His conducting career also continued to thrive with positions at the Berlin State Opera and the Vienna State Opera.

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Don Juan op 20 (1888)

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra

Mariss Jansons (conductor)

Richard Strauss’s tone poems from the 1890s, such as Till Eulenspiegel, Also sprach Zarathustra, Don Quixote, and Ein Heldenleben, were a big departure from traditional music. They jettisoned the serious, mystical ethos of Wagner, opting for irony, personal stories, and ideas inspired by Nietzsche. By mixing complex storytelling with bold harmonies and experimental orchestration, Strauss became known as a provocative modernist who sparked both admiration and controversy.

Don Juan, Strauss’s tone poem from 1888, was inspired by Nikolaus Lenau’s version of the legend. It premiered in Weimar in 1889 with Strauss conducting. The piece is famous for its colourful orchestration and storytelling, capturing the tragic story of Don Juan, who’s obsessed with finding the perfect woman. This obsession leads him to a life of promiscuity and despair. Strauss masterfully conveys this through music, shifting from energetic to melancholic themes, ending with Don Juan’s tragic downfall. The rich orchestration really brings his romantic adventures to life and despite some initial criticism, Don Juan cemented Strauss’s place as a key figure in modern music and remains a celebrated example of program music.

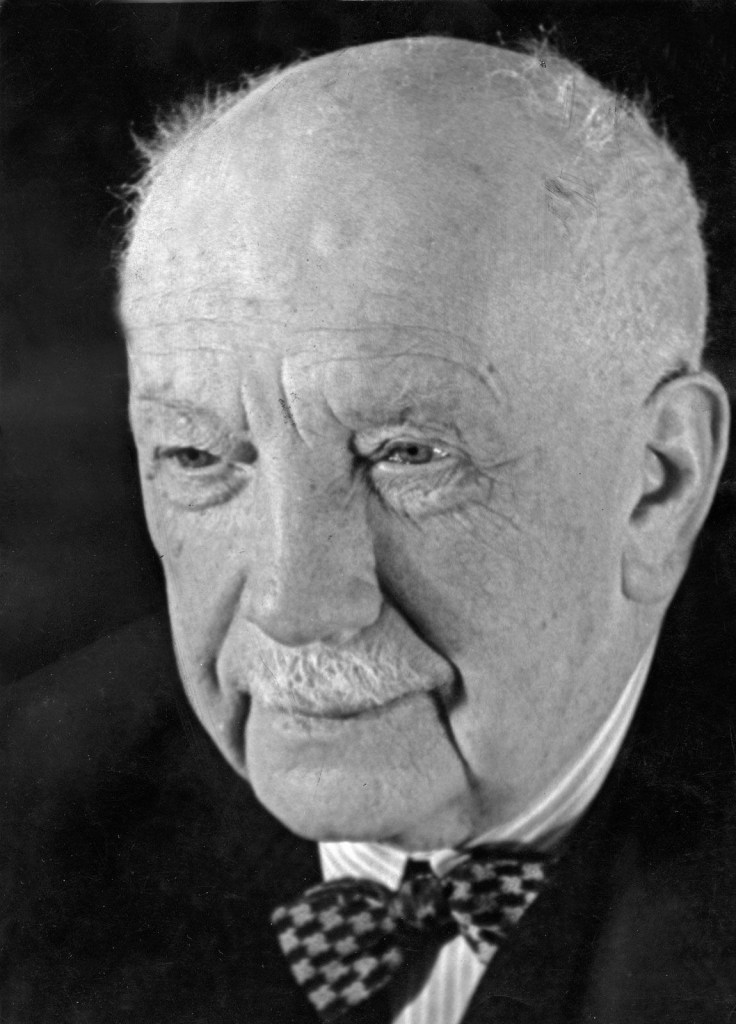

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Also Sprach Zarathustra op 30 (1896) – II. Of Joys and Passions – The Song of the Grave

London Philharmonic Orchestra

Klaus Tennstedt (conductor)

Richard Strauss’s tone poems were divisive during Strauss’s lifetime. People highly regarded Don Juan for its sumptuous orchestral sound but some critics thought the subject matter was unacceptable. Ein Heldenleben, on the other hand, was lampooned by the critics for being too self indulgent. In Britain, people were impressed by Strauss’s technical skills, but some critics weren’t sure about his creativity, partly because they weren’t fans of German modernism. Conductors such as Henry Wood were big supporters of Strauss’s music but critics like Ernest Newman were torn between loving Strauss’s innovation but feeling uneasy about how intense the music was emotionally. Also sprach Zarathustra is a bold piece, inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous book that said traditional beliefs were outdated due to science and philosophy. Strauss used Nietzsche’s ideas to explore humanity’s evolution, reflecting the concept of the ‘Superman,’ even though he said it wasn’t a direct interpretation of Nietzsche’s philosophy. Nietzsche’s idea of the Übermensch (Overman) is reflected in Strauss’s musical heroes like Don Juan, Till Eulenspiegel, and the hero from Ein Heldenleben. These characters are all about breaking free from societal norms, which matches Strauss’s own rejection of traditional artistic rules.

After finishing his book Zarathustra, Nietzsche wondered where it truly belonged, suggesting it might fit among symphonies. Richard Strauss answered this question with his stunning tone poem Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Strauss believed that using a programme was a legitimate way to convey unified artistic ideas, especially when traditional forms didn’t fit. He drew inspiration from Nietzsche but used it freely, focusing on the evolution of humanity and the idea of the “superman.” His music is a tribute to Nietzsche’s genius, capturing the emotional journey from naive belief to more complex themes. Also sprach Zarathustra includes musical references to religious chants, reflecting Strauss’s deep respect for Nietzsche’s philosophical ideas.

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Ein Heldenleben op 40 (1898) – The Hero’s Field of Battle

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Bernard Haitink (conductor)

Strauss’s innovative orchestration—featuring techniques like divisi strings, extended brass methods, and unique percussion—transformed symphonic composition. His skill in evoking vivid imagery, such as the flutter-tongued woodwinds mimicking bleating sheep in Don Quixote, set a new benchmark for programmatic realism. The tone poems influenced a wide range of 20th-century composers, from Korngold and Holst’s cinematic grandeur to Shostakovich’s psychological depth. Their structural fluidity also anticipated the through-composed forms found in modernist works by Berg and Schoenberg.

Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben stands as his most explicitly autobiographical tone poem, structured as a six-section story tracing his artistic journey. The work portrays his professional conflicts, romantic devotion and confrontations with critics. Through quotations from earlier compositions like Don Juan and Till Eulenspiegel – a practice later termed ‘self-borrowing’ – Strauss asserts his artistic legacy with unapologetic confidence. While contemporaries criticised its perceived egotism, the piece is highly regarded for merging personal storytelling with orchestral virtuosity, exemplifying Strauss’s bold fusion of introspection and symphonic ambition.

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

An Alpine Symphony op 64 (1915) – XXI Conclusion

Philadelphia Orchestra

Andre Previn

By the mid-20th century, Richard Strauss’s tone poems held an important place in the orchestral repertoire. Conductors such as Wilhelm Furtwängler and Herbert von Karajan regularly performed Strauss’s works because they were both technically precise and emotionally powerful. Scholars also started to dig deeper into the philosophical ideas behind them. The tone poems are challenging to perform and the exploration of themes such as identity, authority and artistic legacy keeps them relevant in modern discussions about postmodernism.

An Alpine Symphony is a huge tone poem that takes us on a day-long hike up an Alpine mountain. Written in 1915, it’s a single, continuous piece that lasts about 50 minutes and is divided into 22 sections. These sections have relevant titles such as Sunrise, The Ascent, On the Glacier, and Thunderstorm and Descent, bringing the journey to life with vibrant orchestral colors and storytelling. Strauss uses a huge orchestra of over 120 musicians to paint the Alpine landscape. The musical journey goes through forests, meadows, and icy glaciers before hitting the summit, where the music celebrates the climbers’ victory. On the way down, a wild thunderstorm erupts, leading to a peaceful sunset and back to night. Strauss was inspired by his own hiking adventures, making An Alpine Symphony more than just a traditional symphony – it’s a mix of vivid music and profound ideas about life.

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Symphonia Domestica op 53 (1903) – Finale

Munich Philharmonic

Zubin Mehta (conductor)

Many scholars have echoed Newman’s scorn for Symphonia Domestica, questioning whether a serious composer should focus on such personal family details, including intimate moments and domestic disputes. However, for Richard Strauss, family was central to his life and creativity. His wife Pauline, a renowned soprano with a fiery personality, and their son Franz (‘Bubi’), born in 1897, brought him joy and stability. So, Strauss decided to express this domestic happiness in music.

In 1903, he began composing Symphonia Domestica, dividing it into four sections that loosely follow a symphony structure. Each family member has their own theme: the father, mother, and baby are all musically represented, with Bubi depicted by a soothing oboe d’amore. The piece captures a day in Strauss’s family life, featuring scenes like baby’s bath time, a lullaby, a chiming clock, a passionate love scene, and a breakfast argument. Strauss initially included detailed descriptions of these scenes in his drafts but later removed them to avoid ridicule from those who preferred grander themes, influenced by Wagner and Mahler.

Symphonia Domestica premiered on March 21, 1904, at Carnegie Hall in New York. Despite needing 15 rehearsals, the performance was praised and Strauss conducted with energy, earning multiple ovations. Two additional performances were held at Wanamaker’s department store, which some critics saw as commercializing art. Strauss defended his choice, stating that true art elevates any space and that earning a respectable fee for his family was not shameful. Despite some criticism, Strauss believed family life was a serious subject worthy of artistic expression. He aimed to create joy through Symphonia Domestica, celebrating the happiness and meaning he found in his family, rather than exploring philosophical themes.

Conclusion: Richard Strauss’s tone poems are a major milestone in Western music history. They blend storytelling, philosophy, and innovative orchestration, connecting the Romantic and modernist periods. By focusing on human stories rather than abstract ideas, Strauss revolutionised programme music and showed how art can change people and cultures. His works were controversial at first, but they remain powerful today because they speak to the complexities of human life. As we face new artistic and existential challenges in the 21st century, Strauss’s tone poems continue to inspire, challenge, and enlighten us.

Leave a comment