The 20th century marked a defining era for American classical music, as composers sought to forge a voice that reflected the nation’s own spirit and identity. In the early decades, American musicians were still deeply influenced by European traditions, but as the country faced the Great Depression, rapid urbanisation, and growing cultural confidence, artists began to look inward for inspiration. Composers such as Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Roy Harris, Walter Piston, and Virgil Thomson stood at the forefront of this artistic awakening.

Drawing on the rhythms, melodies, and energy of American folk music, jazz, and popular song, they created works that captured the sound of a changing nation. These composers built a bridge between European art music and the sounds of everyday American life. Their work mirrored the nation’s search for identity during times of economic struggle, war, and social transformation. By the mid-20th century, American classical music had come into its own—vibrant, confident, and unmistakably rooted in the voices and experiences of its people.

Walter Piston (1893-1976)

Symphony No 6 (1955) IV. Allegro energico

St Louis Symphony Orchestra

Leonard Slatkin (conductor)

Aaron Copland: (1900-1990)

Symphony No 3 (1944–1946) : IV. Molto deliberato (fanfare)

San Francisco Symphony Orchestra

Michael Tilson Thomas (conductor)

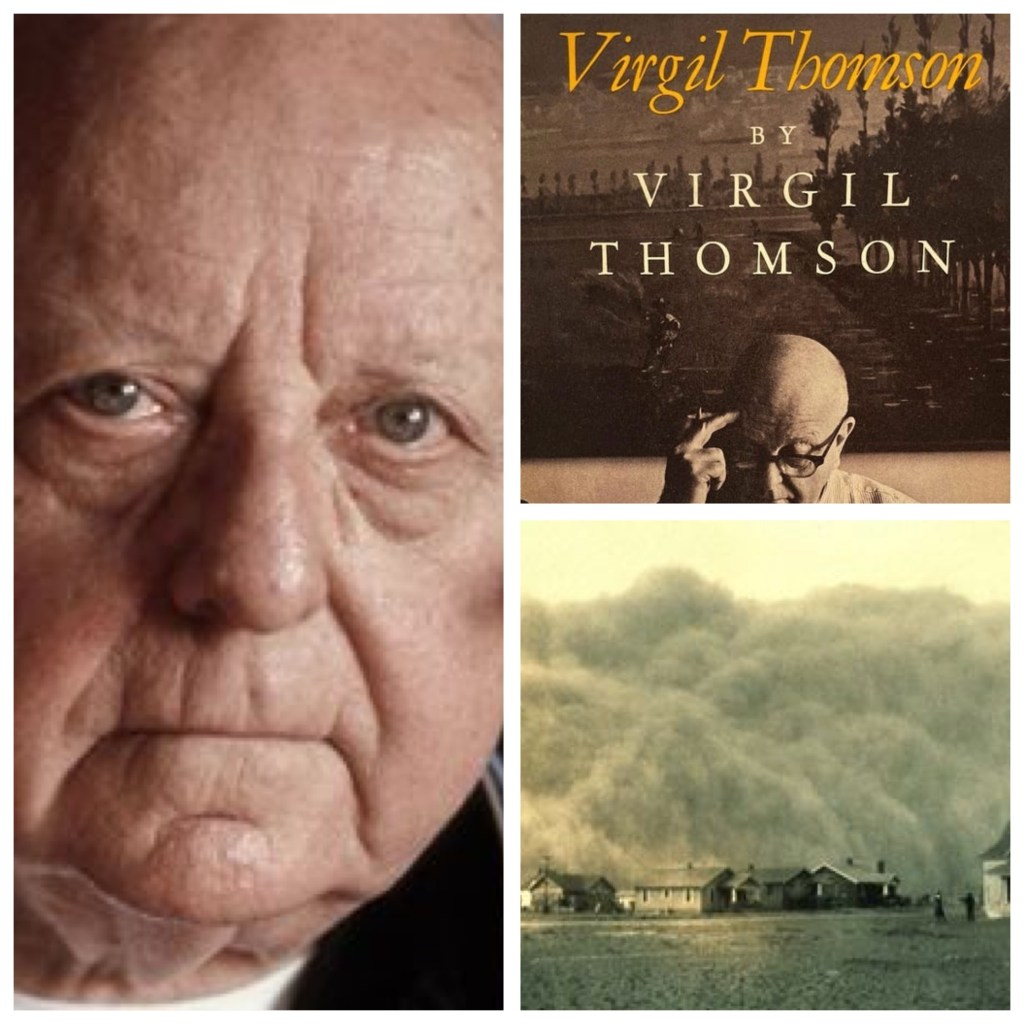

Virgil Thomson: (1896-1989)

The Plough That Broke The Plains (1936): Speculation (Blues)

Post Classical Ensemble

Angel Gil-Ordonez (conductor)

Roy Harris: (1898-1979)

Symphony No 1 (1933) Part 1

Albany Symphony Orchestra

David Alan Miller (conductor)

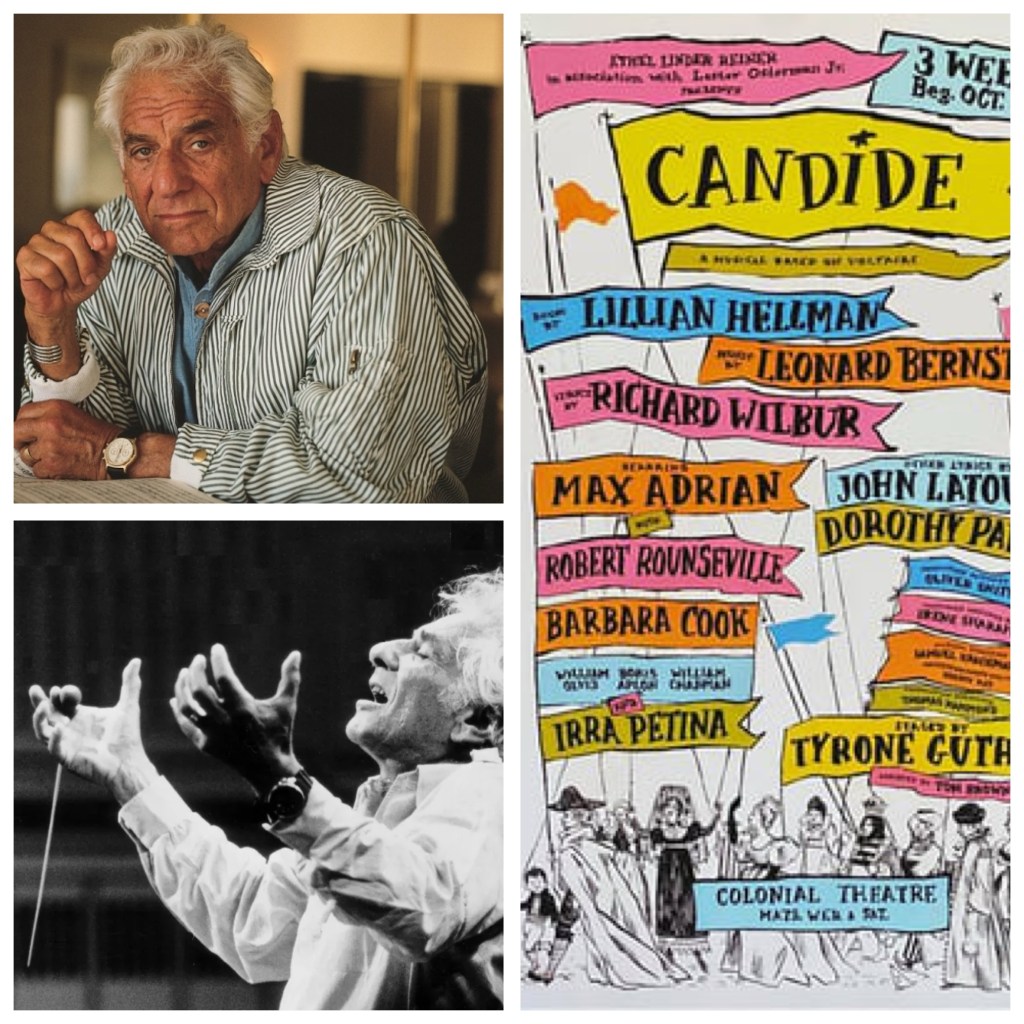

Leonard Bernstein: (1918-1990)

Overture Candide (1956)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra

Leonard Bernstein (conductor)

Walter Piston (1893-1976)

Symphony No 6 (1955) IV. Allegro energico

Born on 20 January 1894 in Rockland, Maine, Walter piston moved to Boston with his family when he was 11. He first tried studying engineering, then moved to the Massachusetts Normal Arts School to major in painting, before finally turning to music. He learned the piano and several other instruments, and served as a musician in the U.S. Navy during the First World War. In 1924 he graduated from Harvard University, receiving the John Knowles Paine Traveling Fellowship.

From 1924 to 1926 he studied composition and counterpoint in Paris with Paul Dukas and Nadia Boulanger. Over his career he wrote eight symphonies; Symphony No. 3 (1947) and Symphony No. 7 (1960) both won Pulitzer Prizes. His output also includes violin concertos, a viola concerto, concertos for various instruments, a large body of chamber music, and the ballet The Incredible Flutist. He wrote influential textbooks on music theory and composition that shaped generations of students. He joined the Harvard University faculty in 1926 and taught there until his retirement in 1960 and was widely regarded as a master composer and theorist. Over his lifetime he received many honours, including three New York Music Critics’ Circle Awards and two Pulitzer Prizes.

His Symphony No. 6 was composed in 1955 to mark the 75th anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and dedicated to the memory of Serge Koussevitzky and his wife, Natalie. It was written very much with the Boston Symphony’s particular sound and strengths in mind.

Aaron Copland: (1900-1990)

Symphony No 3 (1944–1946) : IV. Molto deliberato (fanfare)

Aaron Copland was born in 1900 in Brooklyn, New York, to Russian‑Jewish immigrant parents. He first learned the piano from his older sister and later went on to study composition both in the United States and in Europe. Over time he became one of the leading American composers of the 20th century, famous for weaving American folk and jazz elements into a clear, accessible classical style.

Among his best‑known pieces are Appalachian Spring (which won the Pulitzer Prize), Fanfare for the Common Man, El Salón México, and a number of film scores, including The Heiress, for which he won an Academy Award. Throughout his career he championed new American music, helping to set up organisations such as the American Composers’ Alliance and teaching and mentoring young musicians at Tanglewood. Copland received many major honours, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Congressional Gold Medal, and the National Medal of Arts. He died in 1990, leaving a legacy that continues to define what many listeners think of as the ‘American sound’ in classical music.

Aaron Copland’s Symphony No. 3, written between 1944 and 1946, was commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and premiered there under Serge Koussevitzky in 1946. It is often described as the quintessential American symphony, bringing together Copland’s open, ‘Americana’ style with the depth and architecture of the European symphonic tradition. The work has frequently been hailed as an American masterpiece: powerful, jubilant and heroic, with the finale’s famous fanfare seen as a musical symbol of ordinary people’s spirit and hope in the years just after the Second World War.

The symphony is in four movements, and the fourth makes prominent use of Copland’s well‑known Fanfare for the Common Man, originally composed in 1942. The symphony draws on material related to Fanfare for the Common Man throughout all four movements, with the last movement acting as a triumphant culmination that reflects the end of the war.

Virgil Thomson: (1896-1989)

The Plough That Broke The Plains (1936): Speculation (Blues)

Virgil Thomson was a highly influential American composer and music critic, admired for the originality and dry wit in both his music and his writing. Over a long career, he blended the rhythms of American speech, along with folk and hymn tunes, with a French‑style clarity and humour in his compositions. Born in Kansas City, Missouri, he went on to study at Harvard University, Later, in Paris, he studied with Nadia Boulanger and moved in artistic circles that included figures like Jean Cocteau, Igor Stravinsky and Erik Satie.

Thomson is best known for his operas Four Saints in Three Acts (1927–28), with a libretto by Gertrude Stein and an all‑Black cast at its premiere, and The Mother of Us All (1947), based on the life of Susan B. Anthony. He also wrote powerful film scores for socially engaged documentaries, Alongside composing, Thomson was a prominent and sometimes provocative music critic for the New York Herald Tribune. He also wrote several books, among them an autobiography and American Music Since 1910, helping to shape how audiences and musicians alike thought about 20th‑century music in the United States.

In 1936, Virgil Thomson wrote the score for the documentary film The Plow That Broke the Plains, directed by Pare Lorentz and produced by the U.S. Resettlement Administration to draw attention to the Dust Bowl crisis in the Great Plains. This environmental and human disaster of the 1930s combined severe drought with damaging farming practices, leading to huge dust storms and forcing hundreds of thousands of people to leave their homes and land.

Out of twelve composers approached, Thomson was the only one who agreed to take on the project, accepting a modest fee of 500 dollars and completing the score in less than a week. His music for the film draws on folk songs, hymns, dances and broad chorale‑like writing, using wide, open harmonies and modern orchestral colours to capture both the character and the hardship of life on the Plains. One movement, Blues (Speculation), incorporates features of blues style and acts as a reflective, emotionally charged centre of the suite. It is now recognised as a pioneering work in the development of American documentary film scoring, setting a model for how music can comment on and humanise documentary footage

Roy Harris: (1898-1979)

Symphony No 1 (1933) Part 1

Roy Harris was a key figure in American classical music, celebrated for championing a distinctly home-grown style that captured the spirit of the American landscape. Born in Lincoln County, Oklahoma, he moved to California as a child, later studying at the University of California, Berkeley, and privately with Arthur Farwell and Nadia Boulanger in Paris. He composed over 200 works, including 15 symphonies, and taught at places like Juilliard, Westminster Choir School, and UCLA. Harris co-founded the American Composers Alliance and the International String Congress, and was honoured by the Oklahoma Hall of Fame and the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. He died in Santa Monica, California, in 1979.

His Symphony No. 3 (1939) remains his most famous and often-played work, loved for its single-movement form and its mix of lyrical warmth and dramatic sweep. Roy Harris wrote his Symphony No. 1 – also called 1933 – that same year, marking an early step in his symphonic journey. It’s in three movements: Allegro, Andante, and Maestoso, with the opening Allegro standing out for its lively rhythmic pulse and bold melodic contrasts.

The first movement begins with a striking rhythmic idea – triumphant triplets clashing against steady eighth notes – launched by the timpani and built up by winds and brass. Harris’s gift for soaring, lyrical lines shines through here, with strings rising high over punchy rhythmic foundations, giving the music real drive and flair. Throughout, Harris brings a new seriousness and emotional depth, linking the whole symphony together with intensity and purpose.

Leonard Bernstein: (1918-1990)

Overture Candide (1956)

Leonard Bernstein was a brilliant American conductor, composer, pianist and educator, famous for his electrifying style on the podium and his fresh take on both classical and popular music. He started piano lessons at 10, graduated from Harvard, and then honed his skills in conducting and composition at the Curtis Institute of Music. His big break came in 1943, aged just 25, when he stepped in at short notice for Bruno Walter as assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic—and won instant national fame. From 1958 to 1969 he was the orchestra’s first American-born music director, and he did wonders for classical music by bringing it to TV through his Young People’s Concerts and a huge catalogue of recordings.

Bernstein’s compositions ranged widely, from the iconic Broadway musical West Side Story and operas like Candide to orchestral works such as the Jeremiah Symphony and Chichester Psalms. Off the stage, he was a passionate humanitarian and teacher, inspiring generations with his performances, talks and tireless push for arts and cross-cultural understanding.

Leonard Bernstein’s Overture to Candide (1956) comes from his operetta of the same name, and it’s a sparkling concert piece full of wit, polish and boundless energy – think the playful spirit of Offenbach or Gilbert and Sullivan. Though the original Broadway show had a brief run, this overture has carved out its own stellar reputation and gets played all the time on its own. The scoring is vivid and full-blooded and bursts open with a bold fanfare, grabbing your attention right from the start.

Leave a comment