Argentina’s music is full of colour and energy, a reflection of a country where rhythm and creativity run deep. From the haunting beauty of tango to lively folk dances like the chacarera and zamba, every region contributes its own voice and character. Argentina also has a proud place in the classical tradition, with composers such as Alberto Ginastera and Astor Piazzolla blending national style with modern ideas. Today, that spirit of innovation is stronger than ever, as musicians combine traditional sounds with contemporary genres – electronic, hip hop, and pop – to create something fresh and exciting. Wherever you travel, from the bustling streets of Buenos Aires to the quiet towns of the interior, music is at the heart of Argentine life – a living conversation between past and present, tradition and invention.

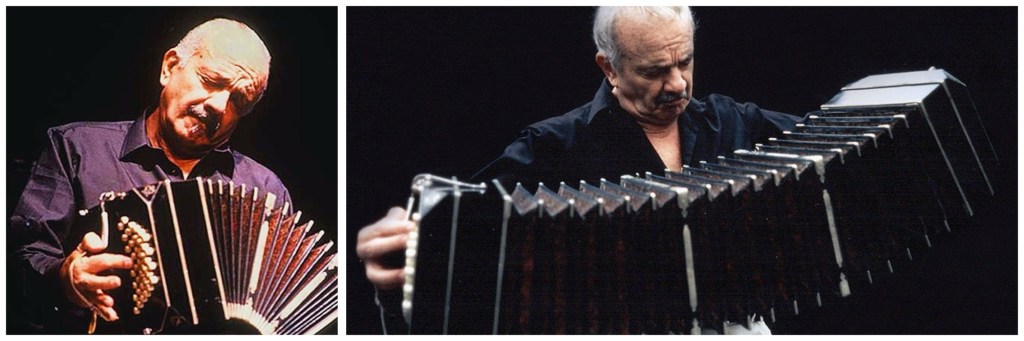

Astor Piazzolla (1921–1992)

Tres minutos con la Realidad

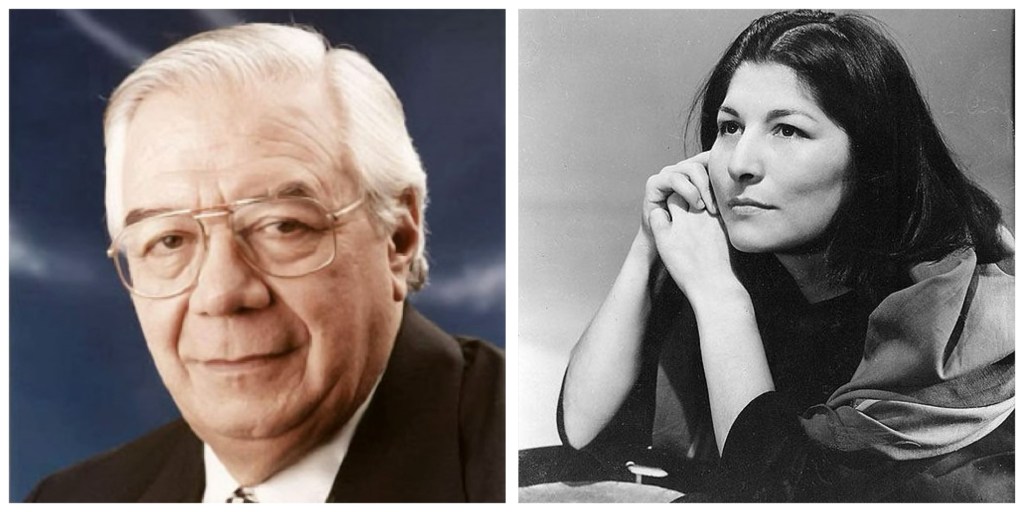

Mauricio Kagel (1931–2008)

Variété V: Giusto

Ensemble Modern

Ariel Ramírez (1921–2010)

Misa Criolla: Kyrie

Mercedes Sosa

Osvaldo Golijov (b. 1960)

Ainadamar: Act 2 Federico: Quiero cantar entre las explosions

Dawn Upshaw (soprano)

Kelley O’Connor (mezzo)

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra

Gonzalo Grau (conductor)

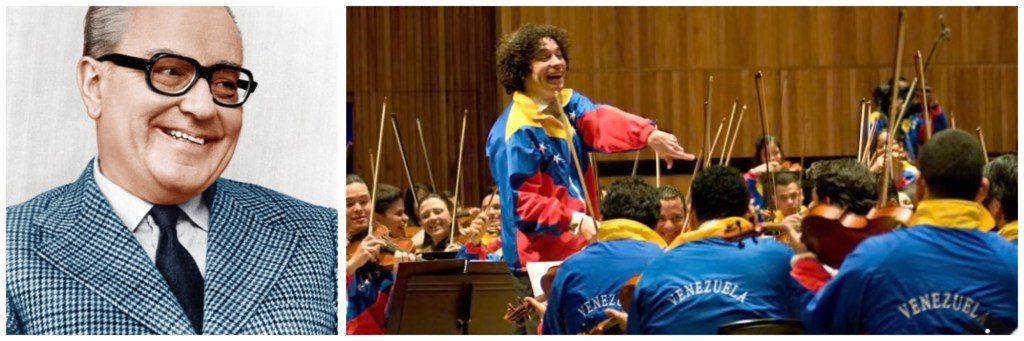

Alberto Ginastera (1916–1983)

Estancia/Danzas del ballet: Danza Final – Malambo

Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra

Gustavo Dudamel (conductor)

Astor Piazzolla (1921–1992)

Tres minutos con la Realidad

Astor Piazzolla was born on 11 March 1921 in the seaside city of Mar del Plata, Argentina, into a family of Italian immigrants. When he was still a young boy, his parents moved to New York City, where from 1924 to 1937 he grew up surrounded by the sounds of both jazz clubs and immigrant street musicians. It was there, in the bustling mix of cultures, that he first learned to play the bandoneón – a small Argentine concertina that would become his lifelong passion. He also studied piano and began exploring classical music, developing an early sensitivity to melody and rhythm.

At the age of 13, he was introduced to the legendary tango singer Carlos Gardel. Piazzolla played in Gardel’s circle for a brief time and even recorded for one of his films. Gardel, impressed by the boy’s talent, invited him to join a tour – an offer his father declined, a decision that ultimately saved Piazzolla’s life; the plane carrying Gardel and his orchestra later crashed, killing everyone on board. Returning to Buenos Aires in 1937, Piazzolla immersed himself in the city’s vibrant tango scene and began formal composition studies with Alberto Ginastera, one of Argentina’s foremost composers. His deep curiosity about harmony and form drew him toward classical models, and by the mid-1940s he had formed his own orchestra. Yet after only a few years, he decided to set performing aside to devote himself to composition.

Winning a major competition in 1951 opened the door to study in Paris with the great pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. It was she who changed the course of his career, encouraging him to embrace his tango roots rather than hide them within classical structures. Her advice freed him artistically, leading to the birth of his groundbreaking Nuevo Tango style – a bold fusion of tango, jazz, and classical music. Back in Buenos Aires from 1955 onwards, Piazzolla faced fierce criticism from tango purists, but he remained undeterred. He later spent a period in the United States before returning to form his celebrated Quinteto Nuevo Tango in 1960.

Over his lifetime, Piazzolla composed around 750 works, including Adiós Nonino, María de Buenos Aires, and Five Tango Sensations. Among his early experimental pieces is Tres minutos con la realidad (1957), whose driving 3-3-2 rhythm reveals the influence of Stravinsky and foreshadows the rhythmic power of his mature style. Through persistence and innovation, Piazzolla transformed the tango from a dance of the streets into a sophisticated art form heard in concert halls around the world. Today, he is remembered not merely as a composer or bandoneón virtuoso, but as the visionary who redefined the very soul of Argentine music.

Mauricio Kagel (1931–2008)

Variété V: Giusto

Mauricio Kagel (1931–2008) was one of those rare artists who seemed to live at the crossroads of sound, theatre, and imagination. Born on Christmas Eve in 1931 in Buenos Aires, he grew up in a Jewish family with Russian and German roots – a cultural mix that would later feed his curiosity about identity, irony, and art. He wasn’t just a composer in the conventional sense; he was an inventor of musical experiences, always pushing at the limits of what a concert could be. As a student at the University of Buenos Aires, Kagel studied music, philosophy, and literature – a combination that already hints at his lifelong curiosity about the ideas behind art. He absorbed influences from Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera, and from the surreal, labyrinthine writings of Jorge Luis Borges. By his teens, he was taking private lessons in piano, cello, conducting, and singing, and by sixteen he had joined the Agrupación Nueva Música, a group dedicated to contemporary music. Just a few years later, in 1950, Kagel co-founded Argentina’s Cinémathèque and released his first published compositions, Palimpsestos and Dos Piezas para Orquesta.

By the mid-1950s, Kagel was already a regular presence at the Teatro Colón – first as a conductor, then as an opera supervisor. But in 1957, his life took a decisive turn when he moved to Cologne, West Germany. There he entered a new world of experimentation, joining a circle of avant-garde composers that included Karlheinz Stockhausen and György Ligeti. In Cologne, Kagel became a key figure in experimental and electronic music, developing what he called Neues Musiktheater – literally ‘new music theatre’ – a hybrid form that mixed sound, movement, absurd humour, and social satire.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Kagel became a major international presence. He taught at the Darmstadt Summer Courses for New Music, founded the Cologne Ensemble for New Music in 1960, and continued writing works that challenged the very definition of performance. His concerts often looked like theatre, with musicians playing, acting, miming, or even parodying their own roles. Audiences were invited not just to listen, but to watch music unfold.

Among his many inventive works, one stands out as a quintessential Kagel creation: Variété (1976–77), subtitled Fantasy for Four Acrobats and Six Musicians. Premiered in Metz in 1977, it’s a witty, circus-like spectacle where musicians share the stage with acrobats, dancers, jugglers, and magicians. The score – written for clarinet or saxophone, trumpet, piano or electric organ, accordion, percussion, and cello – is divided into eleven contrasting movements that alternate lyrical stillness with bursts of comic energy. With theatrical lighting, stage tricks, and multimedia projections, Variété turns the concert into a playful hybrid of music hall, magic show, and abstract theatre.

Full of humour, irony, and imagination, Kagel’s work invites us to rethink what performance can be. For him, music was never just sound – it was gesture, image, and idea. Whether in Variété, his film projects, or his chamber works, Kagel left behind a legacy of curiosity and mischief that continues to inspire composers and performers around the world.

Ariel Ramírez (1921–2010)

Misa Criolla: Kyrie

Ariel Ramírez (1921–2010) was one of Argentina’s most beloved and influential composers, a musician who managed to blend the sacred, the folk, and the classical into something uniquely his own. Born in Santa Fe, he began his musical journey immersed in tango but soon found himself drawn to the songs and rhythms of Argentina’s rural heartland. The traditions of the gauchos and criollos captured his imagination, shaping a lifelong devotion to the sounds and stories of his country.

Ramírez studied piano in Argentina before heading to Europe to pursue composition in Madrid, Rome, and Vienna between 1950 and 1954. While he learned from classical traditions abroad, he always carried Argentina with him. Inspired by the great folk singer Atahualpa Yupanqui, he spent years travelling across the country collecting more than 400 songs – a remarkable effort that reflected his passion for preserving and celebrating folk music. That same spirit inspired him to found the Compañía de Folklore Ariel Ramírez, dedicated to performing and promoting Argentine folk traditions.

Over the course of his career, Ramírez composed more than 300 works and collaborated frequently with poet Félix Luna, creating some of Argentina’s most enduring musical partnerships. From 1970, he also served as the first president of the Argentine Society of Authors and Composers (SADAIC), helping to represent and protect the rights of artists nationwide.

His best-known work, Misa Criolla (1964), earned him worldwide acclaim. Composed soon after the Second Vatican Council allowed Mass to be celebrated in local languages, the piece was revolutionary — one of the first liturgical settings written in Spanish and infused with indigenous instruments and folk rhythms. Ramírez used styles such as the vidala, carnavalito, and chacarera to express the warmth and exuberance of Argentine faith and culture. The result is a deeply spiritual work that feels both timeless and alive, bridging the worlds of church and village, devotion and dance.

When Ariel Ramírez passed away in 2010, he left behind a legacy that continues to resonate far beyond Argentina. Through Misa Criolla and his many other works, he gave voice to a nation – celebrating its traditions while speaking a universal language of faith and humanity.

Osvaldo Golijov (b. 1960)

Ainadamar: Act 2 Federico: Quiero cantar entre las explosions

Osvaldo Golijov was born on 5 December 1960 in La Plata, Argentina, into an Eastern European Jewish family whose home pulsed with music. From an early age, he was surrounded by a striking mix of influences: the elegance of classical chamber music, the soulful chants of Jewish liturgy, the infectious energy of klezmer, and the fiery tangos of Astor Piazzolla that seemed to echo from every corner of Buenos Aires. That rich cultural environment shaped a composer who would grow up to blend worlds few thought could coexist so naturally.

Golijov studied piano in his hometown before turning to composition under the guidance of Gerardo Gandini. Wanting to deepen his understanding of both his cultural roots and contemporary styles, he moved to Jerusalem to study at the Rubin Academy with composer Mark Kopytman. There he encountered Middle Eastern musical traditions, broadening his palette even further. In 1986, he relocated to the United States for doctoral studies at the University of Pennsylvania, where he completed his Ph.D. in composition.

In the early 1990s, Golijov began collaborating with daring ensembles such as the St. Lawrence and Kronos quartets – partnerships that became laboratories for his unique musical language. His style defies category, weaving classical craft together with Latin American rhythms, Jewish spirituality, and the vitality of popular music. His major breakthrough came in 2000 with La Pasión según San Marcos – a retelling of the Passion story bursting with Latin percussion, dance, and choral energy. Its premiere astonished audiences and critics alike, earning Grammy and Latin Grammy nominations and establishing Golijov as one of the most original compositional voices of his generation.

His opera Ainadamar (Fountain of Tears), with a libretto by David Henry Hwang, transforms the final moments of actress Margarita Xirgu into a meditation on memory and sacrifice, as she recalls the life and death of Spanish poet Federico García Lorca. The score fuses flamenco, rumba, and Andalusian song with sweeping orchestral colour, creating a sound world both timeless and immediate. Since its 2003 premiere, Ainadamar has earned two Grammy Awards and global acclaim, cementing Golijov’s reputation for blending folk, sacred, and classical traditions into art that speaks powerfully to the human spirit.

Alberto Ginastera (1916–1983)

Estancia/Danzas del ballet: Danza Final – Malambo

Alberto Ginastera, born on 11 April 1916 in Buenos Aires to a Catalan father and Argentine mother, became one of South America’s most influential and distinctive composers. His musical journey began early with private lessons, and he later went on to study at the National Conservatoire of Music in Buenos Aires. From the start, Ginastera’s music sang of Argentina – its landscapes, traditions, and spirit. His early works, such as Piezas infantiles and the ballet Estancia, pulse with a strong nationalist energy. At just 22, he won first prize for Piezas infantiles, marking him as a rising star of Argentina’s vibrant musical scene.

In 1946, Ginastera was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which took him to the United States – a turning point in his life. There he encountered a wider world of sound, meeting composers and performers who expanded his musical vocabulary. When he returned to Argentina, he dedicated much of his time to teaching, serving at the National Conservatory and eventually becoming Dean at the Catholic University.

By the 1950s, his style began to shift. The folk-inspired rhythms of his youth evolved into a bold, modernist language – full of twelve-tone techniques, shimmering polytonality, and raw emotional power. This period reflected both his restless artistic curiosity and the political turbulence of Argentina at the time. In 1969, frustrated by unrest and censorship, Ginastera left the country and settled in Geneva with his second wife, cellist Aurora Natola. There he continued to compose until his death in 1983, blending modernist experimentation with echoes of Argentina’s folk melodies. He now rests at Geneva’s Cimetière des Rois, not far from fellow Argentine Jorge Luis Borges.

Among his most enduring works is Estancia, a ballet celebrating rural life on the pampas and the heroic spirit of the gaucho. Its final movement, Danza Final – the exhilarating malambo – bursts with stamping rhythms, hand-clapping, and dazzling energy. Premiered in full at the Teatro Colón in 1952, Estancia became a hallmark of Ginastera’s genius: music that marries classical sophistication with the raw, rhythmic vitality of the Argentine land itself.

Leave a comment