Music from Bohemia traces its roots back to the Middle Ages in the monasteries of the Bohemian Forests where Gregorian chant and religious music were performed for centuries. With the arrival of the Reformation, secular music began to take hold and during the 17th Century Bohemian composers stepped up to the forefront. After the transition into the Romantic era, nationalism emerged as a potent force all over Europe. This impacted on Bohemian music so many notable Bohemian composers such as Dvořák and Smetana developed there own musical language firmly rooted in the musical culture of Bohemia

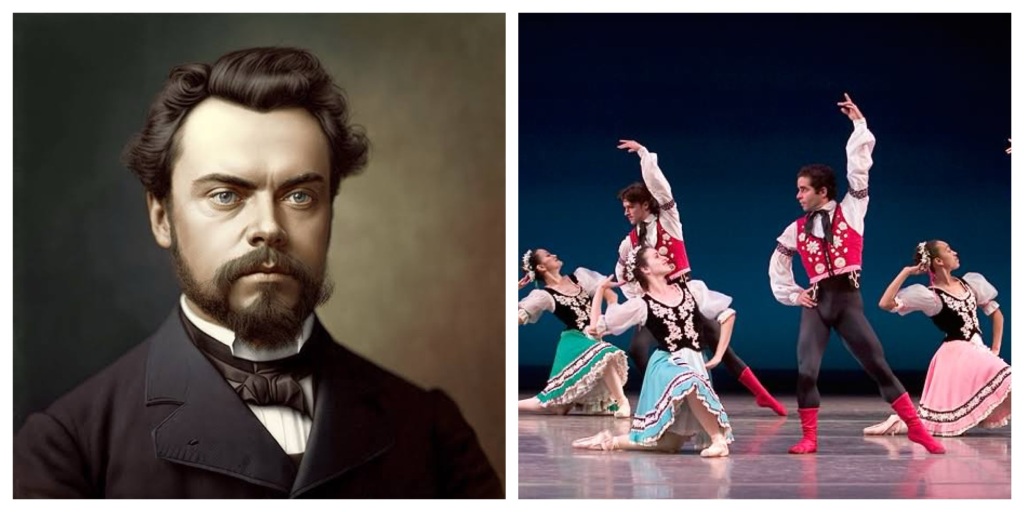

Antonín Dvorák (1841-1904).

Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, B. 83: No. 8, Furiant

Concerto Budapest

Andras Keller (conductor)

Jan Dismas Zelenka (1679-1745)

Barbara, dira effera, ZWV 164: I. Barbara, dira, effera

Il Pomo D’oro

Francesco Corti (conductor)

Jakub Józef Orliński (countertenor)

Jan Vaclav Antonín Stamic (1717-1757), (Johann Wenzel Stamitz)

Symphony in D Major, Op. 3, No. 2: IV. Prestissimo

New Zealand Chamber Orchestra

Donald Armstrong (conductor)

Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884)

The Bartered Bride, JB 1:100: Dance of the Comedians

Vienna Philharmonic

Christoph Eschenbach (conductor)

Dvorák, who began his career as a violist in an orchestra conducted by Smetana, distilled the warmth, gaiety and optimism of native Czech music to the classical forms developed by Bach, Mozart and Beethoven.

The most important influence on the young Dvorák was that of his friend and benefactor, Johannes Brahms, who at that time was the last remaining stalwart of the classical tradition.

Dvorák was a great patriot. He fought for years with his publisher, Simrock, to get the titles and lyrics of his compositions, and his Christian name, published in Czech as opposed to German. After he had achieved international stature as a composer, he won.

The Czechs viewed Dvorák, like Smetana, as an artistic champion of Czech nationhood.

When he died, the people of Prague learned of his death when they came one night to the opera and found the auditorium of the National Theatre draped in black.

When Johannes Brahms told his publisher Fritz Simrock about an exciting but largely unknown Czech composer named Antonín Dvořák, Simrock jumped at a new opportunity to capitalize on a growing interest in folk music among music lovers all over Europe.

Simrock asked Dvořák to compose a set of dances modeled after Brahms’ popular and commercially successful Hungarian Dances.

Dvořák complied, writing a set of six Slavonic Dances originally for four-hand piano.

Soon after he completed the piano version, Dvořák orchestrated them.

They were an immediate success and remain some of Dvořák’s most popular works.

Unlike Brahms’ Hungarian Dances, which are arrangements of actual folk songs, the melodies of Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances are wholly original, composed in folk style.

No. 8, a Czech furiant, is often performed as a stand-alone piece.

Zelenka’s was employed as a double bass player in about 1710 at the court of August the Strong.

Soon his activities as a composer were drawing attention. In order to complete his musical training, the Electoral Prince allowed him to undertake study trips between 1716 and 1719 to Italy and Vienna where he took lessons with Johann Joseph Fux.

Although Zelenka had a promising career it had begun to waver by 1730.

The Saxon heir to the throne, Prince Friedrich August II, had discovered his love for the modern Italian style and a young German composer, Johann Adolf Hasse, was being celebrated as his style was brilliant, melodious and simple, and immediately swept away the works of older composers.

Zelenka’s complex and ornate style he did not stand a chance against Hasse’s disarming simplicity so sadly Zelenka became withdrawn, composed far less and died an embittered, broken man.

However, his surviving compositions often have a grandeur and contrapuntal mastery which can be compared to Zelenka’s friend and colleague, Johann Sebastian Bach.

Zelenka’s Barbara dira effera probably dates from around 1733, when his star was being eclipsed by new operatic developments.

Although a church motet, it displays Zelenka’s brilliant sense of theatricality.

Described as a ‘rage aria for the church’, it may have been composed to remind the new elector that he could perfectly well produce thrillingly dramatic works.

Jan Vaclav Antonín Stamic, known in Germany as Johann Wenzel Stamitz, who with his sons Jan and Karel, founded the well-known Mannheim School.

In Mannheim they set a new standard of quality for orchestral performance for all of Europe and expanded the compositional format of the symphony, paving the way for Franz Joseph Haydn.

Stamic’s innovative approach to composition anticipated the new classical musical period and he became an important influence on the classical style.

His colourful music and fresh, courageous ideas were even admired by Mozart

He was also regarded as the best conductor of his times.

His style included the development of large crescendos and decrescendos along with his development of classical sonata form. In his symphonies he also included a minuet between the usual second and third movements, forming the standard four part sonata.

His instrumentation extensively used wind instruments (horns and clarinet particularly were later used by Mozart in a similar way).

He also abandoned the common general bass line and gave the bass part an independent role in the orchestra.

Importantly, musical ideas were often influenced by Czech traditional folk music.

Smetana is regarded as the founder of a Czech national music.

An ardent patriot, he even manned the barricades during the 1848 Prague uprising which was eventually crushed by the Hapsburgs.

Like Beethoven, he was confronted by the personal tragedy of the loss of his hearing (in fact, Smetana was tormented by incessant, painfully dissonant noise)

As a pianist he was a famed interpreter of Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin and Schumann

At the end of his tragic life, during which he lost a wife, several children, his hearing and finally his reason, the Czechs mourned him as a national hero.

Smetana wrote his comic opera The Bartered Bride between 1863 to 1866.

The opera was not successful in its first outing at the Provisional Theatre in Prague and went through four years of revisions.

Finally, in its 1870 premiere, it found its audience and became a world-wide success and was the first Czech opera that made a hit on the international stage.

Smetana was trying to create a true Czech operatic style and he did it through the use of dance forms, such as the polka and furiant, rather than through quotation of folk songs.

Even though Smetana doesn’t use folk melodies, his opera is thoroughly Czech in spirit.